You probably found a dusty plastic case in a junk drawer recently. Inside is a tiny, clear rectangle with two minuscule spools of brown magnetic tape. It’s smaller than a pack of gum. If you grew up in the 80s or 90s, that click-clack sound of a microcassette popping into a recorder is a core memory. But for everyone else, mini tape recorder tapes—specifically the ubiquitous microcassette—feel like an ancient relic from a world before smartphones swallowed every gadget we owned.

It’s weird.

Analog tech is having a massive moment with vinyl and even standard type-I cassettes, but these tiny tapes occupy a different niche. They weren't for high-fidelity music. You didn't use them to record the radio. They were the workhorses of the office, the secret weapon of the investigative journalist, and the only way your dad remembered to buy milk in 1992.

The Confusion Over What a Mini Tape Actually Is

People get the names wrong all the time. Honestly, it’s a mess. When someone says "mini tape recorder tapes," they usually mean one of three distinct formats that look similar but are totally incompatible.

First, you have the Microcassette. This is the king. Introduced by Olympus in 1969, it became the gold standard for dictation. It’s about one-quarter the size of a standard cassette. Then there’s the Minicassette (often stylized as Mini-Cassette), which was a Philips invention. Even though the names are almost identical, they don’t work in the same machines. Philips used a capstan-less drive system, which meant the tape speed fluctuated as the reel got fuller. It didn't matter for voice, but it made them useless for anything else.

Finally, there’s the Picocassette, which is hilariously small. Dictaphone released it, and it's basically the size of a postage stamp. If you find one of those today, good luck finding a working player that doesn't cost more than a used car.

Why the Sound Quality Is... Well, Unique

Let’s be real: microcassettes sound kinda terrible.

Standard cassette tapes (the ones for music) run at 1.875 inches per second (ips). Microcassettes usually run at 0.94 ips, or even a glacial 0.47 ips if you’re trying to squeeze 90 minutes of talk onto a 60-minute tape.

Why does this matter?

The slower the tape moves, the lower the fidelity. You lose all the high frequencies. Everything sounds like it’s happening underwater or through a thick wool blanket. But for a lawyer in 1985 or a doctor dictating notes, that didn't matter. They needed "voice intelligibility," not a concert hall experience. The tape was formulated specifically to capture the human mid-range.

Interestingly, some high-end recorders from brands like Sony (the M-series) or Olympus (the Pearlcorder line) actually had decent frequency response. They used "Metal" tape formulations—rare and expensive now—that could actually capture a broader range of sound. But 99% of the tapes you find in a thrift store are basic Ferric Oxide. They hiss. They warble. And honestly, that’s part of the charm.

The "Journalist" Aesthetic and the Death of the Dictaphone

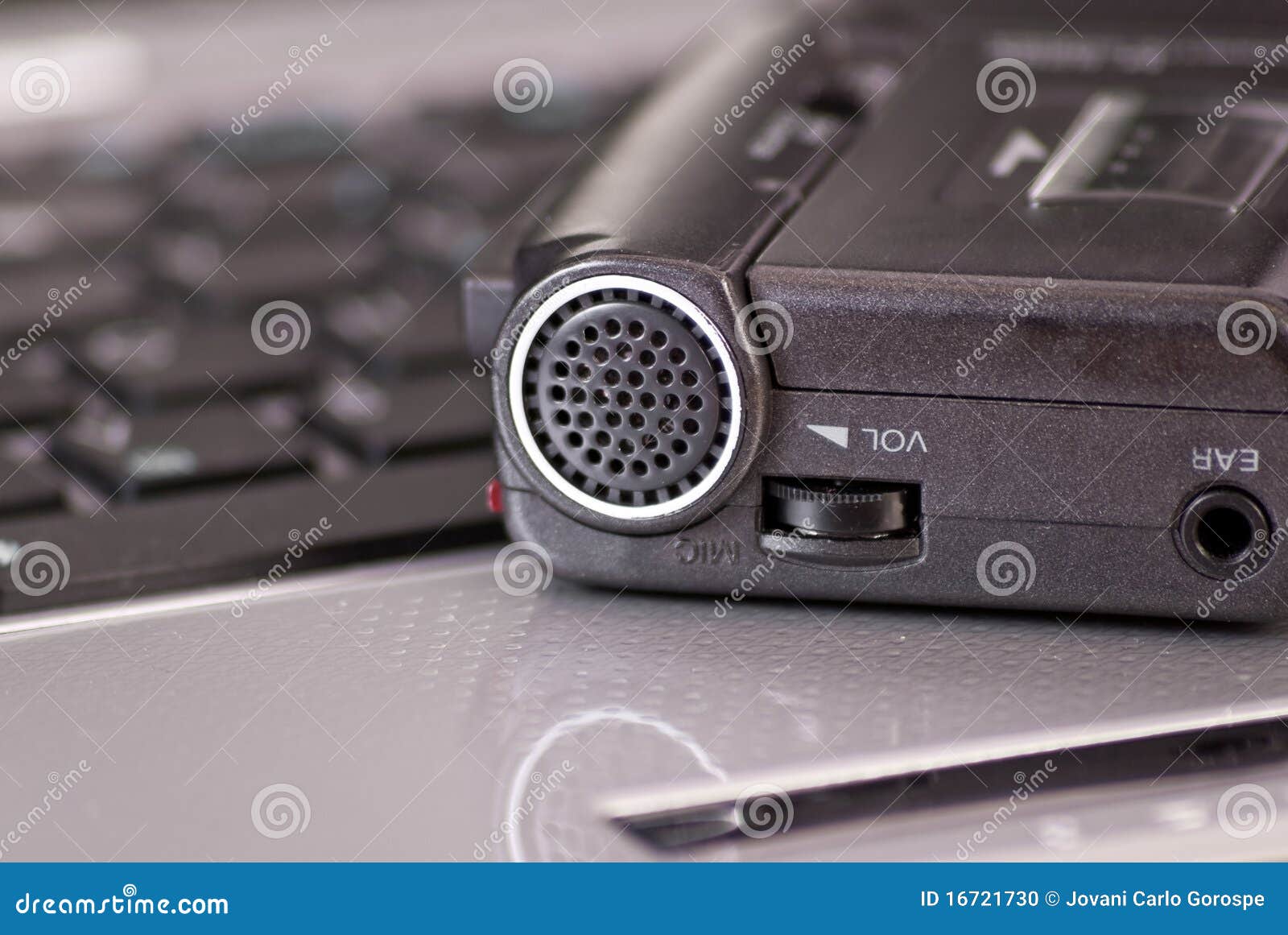

There is something undeniably tactile about hitting a physical "Record" button. You feel the mechanical thud. You see the little wheels spinning.

Before digital voice recorders (DVRs) took over in the late 90s, the microcassette was the symbol of truth-seeking. Think about every movie from that era. If a whistleblower is meeting a reporter in a parking garage, a microcassette recorder is sitting on the dashboard.

Companies like Sony, Olympus, Sanyo, and Panasonic dominated this space. The Sony M-527 or the Olympus Pearlcorder S701 were ubiquitous. They were built like tanks. You could drop them, spill coffee on them, and they’d still keep spinning that magnetic ribbon.

Today, we use voice memos on an iPhone. It’s objectively better. It’s clearer. You can share the file in two seconds. But you lose the physical proof. There is a specific security in holding a physical tape that cannot be remotely deleted or hacked. That’s why some legal professionals and private investigators still hoard New Old Stock (NOS) tapes.

The Fragility of 30-Year-Old Magnetic Ribbon

If you have old tapes, you’re on a clock.

Magnetic tape is just plastic coated in rust (iron oxide) and held together by a binder. Over time, that binder breaks down. It’s called "Sticky Shed Syndrome," though it's less common in microcassettes than in high-end reel-to-reel tapes. Still, the tape can become brittle.

The bigger issue is "print-through." This happens when the magnetic signal from one layer of tape "ghosts" onto the layer underneath it because they’ve been pressed together for decades. You’ll hear a faint echo of the words before they are actually played.

How to Digitizing Those Old Memories

If you find a tape of your grandmother talking or a recording of your first words, don't just shove it into a 20-year-old recorder and hit play. The rubber belts inside old recorders often turn into a gooey, tar-like substance over time. If those belts snap or slip, they can eat your irreplaceable tape.

- Check the recorder first. Open the door, look at the rubber pinch roller (the tiny wheel). Is it shiny or cracked? If so, it might ruin the tape.

- Clean the heads. Use a Q-tip and a tiny bit of 90% isopropyl alcohol. Dirty heads make for muffled sound.

- The Transfer. Run a 3.5mm auxiliary cable from the "Earphone" or "Line Out" jack of the recorder into the "Line In" or "Mic" jack of a computer.

- Software. Use Audacity. It’s free. It’s great.

- Levels. Don't let the red bars hit the top. Analog distortion is okay; digital clipping sounds like garbage.

Finding New Tapes in 2026

Can you still buy them? Yes. Sorta.

👉 See also: The Real Joseph Louis Gay Lussac: Why Science Still Owes Him So Much

Maxell and TDK stopped mass-producing these years ago, but you can still find "New Old Stock" on eBay or at specialty electronics shops. Sony was one of the last holdouts to keep production lines open.

Prices have actually gone up. A pack of three 60-minute microcassettes that used to cost $5 might now run you $20 or $30. People who use them for "Lo-Fi" music production or "Tape Loops" have driven up the demand. Musicians love the "wow and flutter"—that slight pitch instability that makes everything sound nostalgic and haunting.

The Tech Specs Nobody Asks For (But You Need)

Microcassette tapes come in different lengths: MC30, MC60, and MC90.

An MC60 gives you 30 minutes per side at the standard speed. If your recorder has a "2.4cm / 1.2cm" switch, flipping it to 1.2cm doubles your recording time but halves your audio quality. It’s a trade-off. Unless you’re recording a four-hour board meeting where you only need to hear the gist of what’s being said, stay at the faster speed.

Also, watch out for the "End of Tape" sensor. Some high-end recorders used an optical sensor to stop the motor, while cheaper ones just let the motor strain against the end of the plastic leader. This can stretch the tape. If you’re at the end of a side, stop it manually.

What Really Happened to the Market?

The transition to digital wasn't gradual; it was a cliff.

In the early 2000s, Flash memory became cheap enough that companies like Olympus shifted their entire R&D budget to digital recorders. The benefits were too big to ignore. You could index recordings, jump to specific timestamps, and—most importantly—no moving parts meant the devices could be even smaller.

But the microcassette didn't die because it was bad. It died because it was mechanical in a world that became software-defined. There is a massive difference between a file named "memo_01.mp3" and a physical object you can label with a Sharpie and put in a shoebox.

Why You Should Keep Your Player

If you have a working Microcassette recorder, do not throw it away. Even if you don't use it, the secondary market for working analog gear is exploding.

Collectors look for specific models. The Sony M-800V or the Olympus Pearlcorder L400 (which is incredibly tiny and sleek) are highly sought after. They represent a peak in mechanical engineering—hundreds of tiny gears and springs working in perfect synchronization.

Moving Forward With Your Analog Collection

If you're looking to get back into mini tape recorder tapes or just trying to save what’s on them, start with a hardware audit. Check your battery compartments for corrosion. If you see white powder, clean it out with vinegar and a toothbrush immediately; that acid will eat the circuit board.

Once you’ve confirmed your gear works, prioritize your tapes. Start with the ones that look "white" or "cloudy" through the clear plastic window—that’s often a sign of mold or extreme degradation. Those need to be digitized first.

For those looking to buy "new" gear, stick to the big four: Sony, Olympus, Panasonic, or Sanyo. Avoid the modern, unbranded "USB Cassette Converters" you see on big retail sites today. They are almost universally made with cheap, plastic mechanisms that have terrible motor stability. You are much better off buying a used, "tested" name-brand unit from a reputable seller who actually knows what a belt-drive is.

Preserving these tiny bits of magnetic history is a bit of a chore, but once you hear that specific, grainy hiss of a voice from thirty years ago, you'll realize it's worth the effort. There's a soul in the tape that a digital file just can't replicate.