You probably think of glucose as a simple little hexagon. It’s the stuff in your blood, the fuel for your brain, and the reason you get a rush after eating a donut. But honestly, the chemical structure of glucose is a chaotic, shape-shifting mess that refuses to stay still. Most people visualize it as a static drawing on a whiteboard. In reality, if you were to zoom into a drop of your own blood, you wouldn’t see a bunch of identical little hexagons floating around. You’d see molecules constantly snapping open and shut like molecular mousetraps.

Glucose is a hexose. That basically means it has six carbon atoms. Its chemical formula, $C_6H_{12}O_6$, is one of the first things you memorize in organic chemistry, yet that string of letters and numbers hides a massive amount of complexity. It is the most abundant monosaccharide on Earth. It’s the primary building block for cellulose in plants and glycogen in your liver. Without the specific orientation of these atoms, life as we know it would literally collapse because our enzymes wouldn't recognize their fuel.

The straight-chain vs. ring debate

Let's get into the weeds. If you look at glucose in its "dry" form, it can exist as an open-chain structure. This is often called the Fischer projection. Imagine a vertical spine of six carbon atoms. At the very top, you have an aldehyde group—a carbon double-bonded to an oxygen and single-bonded to a hydrogen. This makes glucose an "aldose."

📖 Related: Is 120 bpm normal? What your heart is actually trying to tell you

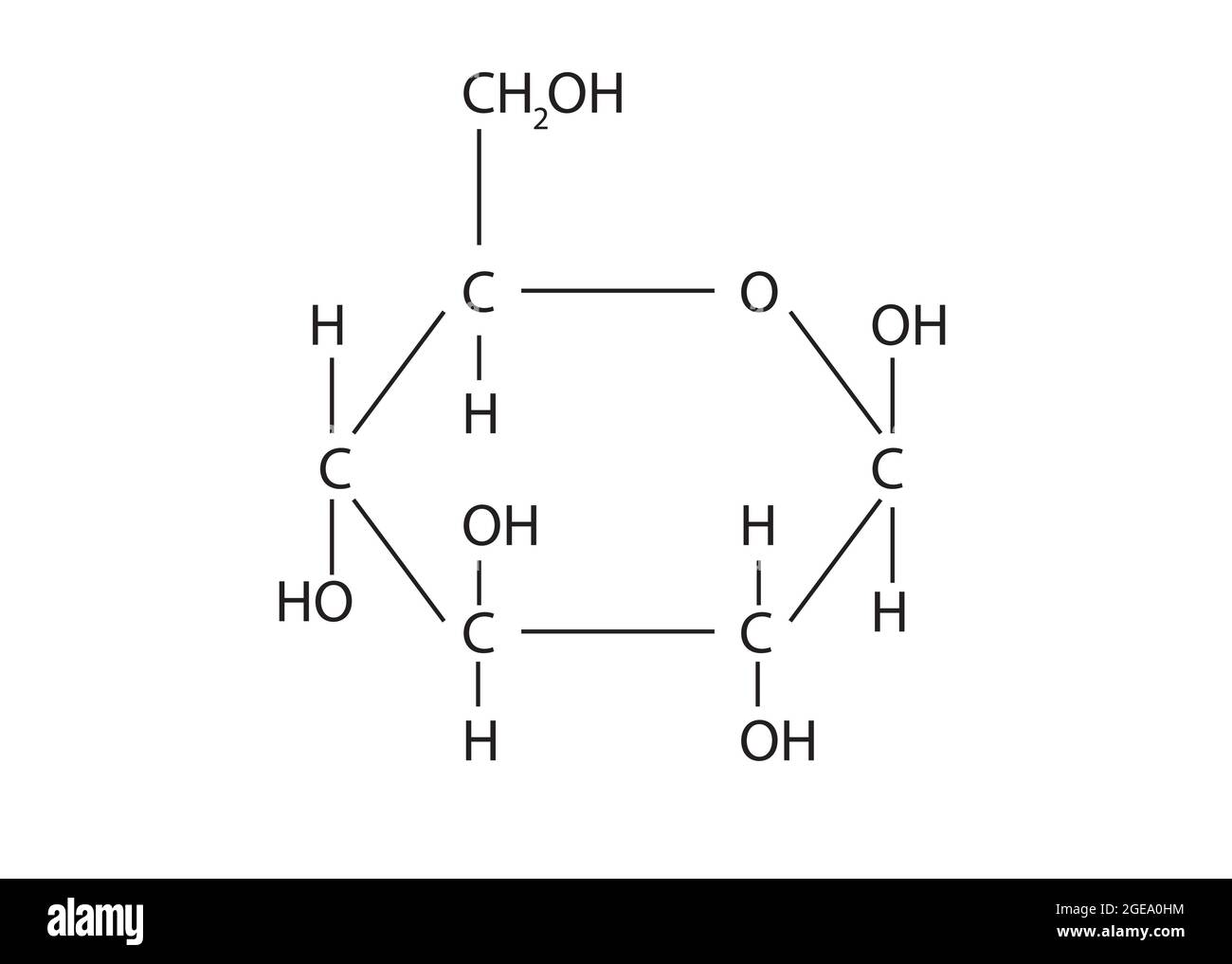

But here’s the kicker: glucose is almost never a straight line when it’s inside your body. Molecules are lazy. They want to be stable. When glucose is dissolved in water (or blood), the hydroxyl group on the fifth carbon reaches around and attacks the aldehyde carbon at the top. This "attack" causes the molecule to curl up into a ring. This isn't a rare occurrence. In an aqueous solution, less than 0.02% of glucose molecules are actually in that straight-chain form at any given moment. The rest are locked into a six-membered ring called a glucopyranose.

Why the "D" in D-glucose actually matters

You’ve probably seen the term "D-glucose" on supplement bottles or in medical papers. That "D" stands for dextro, referring to the chirality—or handedness—of the molecule. Think of your hands. They are mirror images, but you can’t slide a left-handed glove onto your right hand. Molecules are the same.

In the 1890s, Emil Fischer figured out that the orientation of the hydroxyl group ($-OH$) on the asymmetric carbon furthest from the aldehyde group determines this handedness. In D-glucose, that group points to the right. This isn't just a naming convention for nerds. Your body is incredibly picky. It can only process D-glucose. If you were to eat a bowl of L-glucose (the "left-handed" mirror image), it would taste sweet, but your body wouldn't know how to burn it for energy. It would just pass through you.

The alpha and beta flip-flop

Once the ring closes, something weird happens at the first carbon, known as the anomeric carbon. The hydroxyl group can end up pointing "down" or "up."

If it points down (away from the $CH_2OH$ group), we call it alpha-D-glucose.

If it points up (towards the $CH_2OH$ group), it’s beta-D-glucose.

This tiny difference is why you can digest a baked potato but you can't digest a piece of wood. Starch is made of alpha-glucose chains, which our enzymes can easily break apart. Cellulose, the structural stuff in plants and wood, is made of beta-glucose chains. Our digestive systems look at those beta-linkages and basically say, "No thanks."

The process of switching between these two forms is called mutarotation. If you dissolve pure alpha-glucose in water, it will slowly transform until it reaches an equilibrium—about 36% alpha and 64% beta. The beta form is slightly more stable because the hydroxyl groups are spread further apart, reducing "clash" between atoms.

It isn't actually flat

The Haworth projection—those flat hexagons you see in textbooks—is a lie. A convenient lie, but a lie nonetheless.

Carbon atoms like to maintain a tetrahedral bond angle of about 109.5°. You can't achieve that in a perfectly flat hexagon. To relieve the tension, the chemical structure of glucose twists into what scientists call a "chair conformation."

👉 See also: Chemical peel before and after photos: What they don't show you about the process

Imagine a lounge chair. One end of the ring tilts up, and the other tilts down. This allows the bulky side groups (the $-OH$ and $CH_2OH$) to sit in "equatorial" positions, sticking out from the sides rather than poking straight up or down where they would bump into each other. This specific geometric stability is likely why glucose became the "universal fuel" of the biological world. It’s sturdy. It’s reliable. It doesn’t degrade easily compared to other sugars like galactose or fructose.

Practical implications for health and testing

Why does any of this matter outside of a lab? Well, the reactivity of that open-chain form is what causes problems in diabetics.

When blood sugar is high, more glucose is in that open-chain state with a reactive aldehyde group exposed. This aldehyde can spontaneously react with proteins in your blood, like hemoglobin. This is what we measure in an HbA1c test. It’s essentially a measure of how much your proteins have been "sugar-coated" (glycated) over three months.

💡 You might also like: The Map of Obesity in America: Why Your Zip Code Might Matter More Than Your Gym Membership

- Glucose levels and Glycation: High glucose isn't just about energy; it's about the chemical damage that happens when the ring opens up and the aldehyde group starts sticking to things it shouldn't.

- Isomerization: Food scientists use the fact that glucose can be rearranged into fructose to create High Fructose Corn Syrup. They use an enzyme called glucose isomerase to flip the atoms around, making the syrup sweeter and cheaper.

- Standardization: When you use a glucose meter, the strips are usually coated with an enzyme like glucose oxidase, which is highly specific to the D-isomer of the molecule.

Misconceptions about "natural" vs "synthetic" glucose

There's a lot of talk in wellness circles about "natural" glucose from fruit versus "synthetic" versions. Chemically, there is zero difference. A D-glucose molecule extracted from a corn stalk is identical in every way—bond length, bond angle, and atomic weight—to one found in an organic blueberry.

The difference lies in the "packaging." In fruit, glucose is wrapped in fiber, which slows down the rate at which the molecules enter your bloodstream. When you drink a soda, the chemical structure of glucose is hit with zero resistance, leading to that massive insulin spike.

How to use this knowledge

If you're trying to manage your metabolic health, understanding the stability of these structures helps.

- Prioritize Starch over Simple Sugars: Since starch is just a long-chain polymer of alpha-glucose, it requires more enzymatic work to break down than pure dextrose or table sugar.

- Monitor A1c, not just daily spikes: Remember that the open-chain reactivity is a slow-burn process. Your daily finger-prick test is a snapshot; your A1c is the history of how many molecules "unzipped" and stuck to your red blood cells.

- Fiber is the "Beta" shield: Since we lack the enzymes to break beta-linkages in cellulose (fiber), eating fiber alongside glucose acts as a physical barrier, preventing the alpha-glucose from being absorbed too quickly.

To dive deeper into how these structures interact with your unique physiology, you might want to look into continuous glucose monitoring (CGM). It provides a real-time look at how different "linkages" of glucose—whether they come from complex grains or simple fruits—affect your blood chemistry throughout the day.