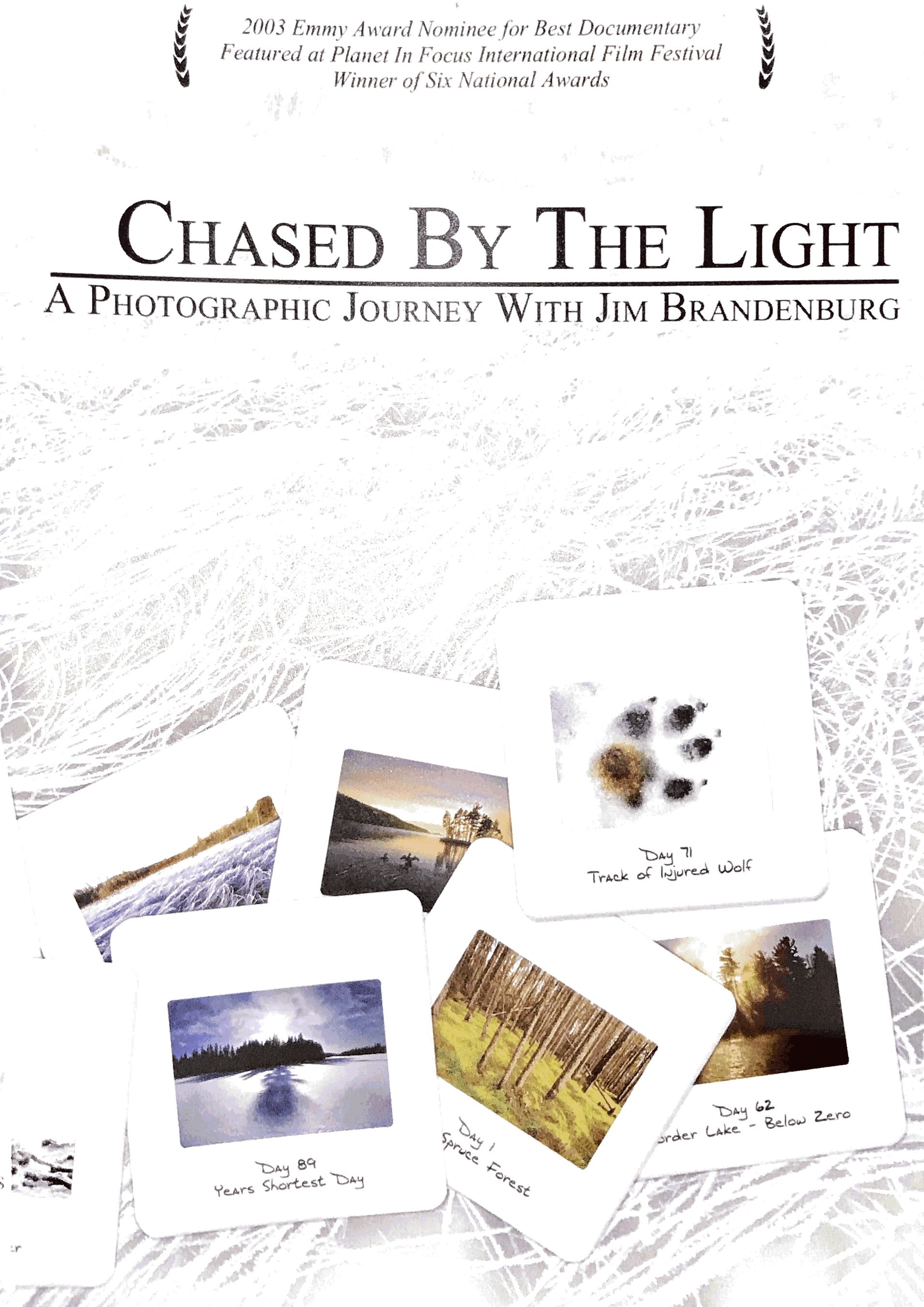

In 1994, Jim Brandenburg was burnt out. You’ve probably felt that itch—the one where your job, even if it's a "dream job" like shooting for National Geographic, starts to feel like a repetitive grind. He was tired of the "spray and pray" method of modern photography, where you burn through rolls of film just to find one decent shot. So, he set a rule that most photographers today would find physically painful: one single frame per day. No second chances. No "safety" shots. Just one click of the shutter between the autumnal equinox and the winter solstice. This project became Chased by the Light, and honestly, it’s still the most stressful thing I’ve ever read about a nature photographer doing.

Think about the sheer audacity of that.

The Mental Toll of One Click

We live in an era where people take thirty photos of a brunch salad. Brandenburg, sitting in the North Woods of Minnesota, would sometimes wait until the very last sliver of light before deciding to commit. If a wolf ran past at 10:00 AM, he had to decide: is this the shot? If he took it, he was done for the day. If he passed it up, he might end up with nothing but a blurry tree at dusk.

The resulting book, Chased by the Light, isn't just a collection of pretty pictures; it’s a psychological study of restraint. He wasn't just taking photos; he was living a self-imposed discipline that mirrored the scarcity of the wilderness itself. Most experts in the field, like those at the International Center of Photography, point to this work as a turning point in "slow photography." It forced a shift from the technical obsession with gear to a spiritual obsession with timing.

What Most People Get Wrong About the Project

A lot of hobbyists think Brandenburg just got lucky ninety times in a row. That’s not what happened. If you look closely at the collection, some days are... well, they’re quiet. They aren't all "epic" sunsets or rare wildlife encounters.

- Day 32 might just be the way frost clings to a leaf.

- Sometimes the "light" he was chasing was barely there at all, a grey, muted Minnesota overcast that would make most Instagram influencers quit on the spot.

- He didn't use fancy filters or digital manipulation (which wasn't really a thing in '94 anyway).

The misconception is that this was a "best of" reel. It wasn't. It was a diary. If the day was bleak, the photo was bleak. That honesty is why Chased by the Light resonates decades later. He wasn't trying to manufacture beauty; he was trying to document his presence within it.

📖 Related: Emily Piggford Movies and TV Shows: Why You Recognize That Face

The Technical Nightmare of 1994

You have to remember the tech. There was no LCD screen on the back of his Nikon. He couldn't check the histogram to see if he blew out the highlights. He was shooting on Fuji Velvia or Kodachrome—slide films known for having almost zero dynamic range. If you missed the exposure by half a stop, the shot was ruined.

And he wouldn't know if he ruined it for weeks.

He had to wait until the film was processed to see if his one-shot-a-day gamble actually paid off. Can you imagine the anxiety of Day 45? You’ve spent six weeks being perfect, and you’re standing in the snow, hands shaking, hoping the light meter isn't lying to you. This is why the project is often cited in workshops by organizations like the North American Nature Photography Association (NANPA). It’s the ultimate case study in "pre-visualization." You have to see the print in your head before you ever touch the button.

Why Chased by the Light Matters in 2026

We are currently drowning in images. AI can generate a "perfect" sunset in four seconds. But AI can’t replicate the intent behind Brandenburg’s work. The "value" of a photo in the modern age has plummeted because the "cost" (effort) has dropped to near zero.

Brandenburg’s project did the opposite. By artificially limiting his supply, he made the value of each frame infinite.

👉 See also: Elaine Cassidy Movies and TV Shows: Why This Irish Icon Is Still Everywhere

Breaking the "Content" Cycle

Basically, we’ve been taught that more is better. More posts, more frames, more engagement. Chased by the Light is a direct rebuttal to that entire philosophy. When he captured that famous image of the lone wolf or the raven in flight, it wasn't "content." It was a culmination.

It’s also worth noting that Brandenburg was already an elite-level pro. He had the "eye" developed over decades. For a beginner to try this, it would be a disaster—but it would be a highly educational disaster. It forces you to look at the world differently. You stop looking for "stuff" to shoot and start looking for "the" shot.

Lessons from the North Woods

If you actually sit down with the book—and I mean the physical book, not just scrolling thumbnails—you notice the rhythm. The project starts with the lush, fiery reds of late September and descends into the stark, monochromatic whites of December.

It’s a countdown.

- The Equinox: Plenty of light, lots of color, high energy.

- The Transition: The leaves drop, the "easy" beauty disappears.

- The Solstice: Survival mode. The light is weak, the days are short, and every shot is a battle against the dark.

He wasn't just chasing light; he was losing it. The book is a record of a man watching the world go to sleep.

✨ Don't miss: Ebonie Smith Movies and TV Shows: The Child Star Who Actually Made It Out Okay

How to Apply the Brandenburg Method Today

You don't need to move to a cabin in Minnesota to learn from this. Honestly, most of us would benefit from a "Diet Brandenburg" approach.

The next time you go out to take photos, leave the 128GB memory card at home. Take a small one. Or, better yet, tell yourself you only have ten shots for the whole afternoon. You’ll find yourself standing still longer. You’ll notice how the shadows move across a building or how the wind changes the texture of water. You become a participant in the environment rather than just a spectator with a camera.

Real-World Actionable Steps

If you're feeling uninspired, try these specific constraints. They’re derived directly from the DNA of Chased by the Light:

- The Power of One: For one weekend, allow yourself exactly one photo per hour. No more. If you see something cool at 10:05, you take it, and then you're a civilian until 11:00.

- Manual Only: Turn off the autofocus. Turn off the auto-exposure. Brandenburg’s era required a level of manual dexterity that we've largely lost. Reclaiming that control makes you feel more "connected" to the final image.

- Print the "Failures": Brandenburg included shots that weren't perfect because they were part of the story. Stop deleting everything that isn't a masterpiece. Sometimes the "mistake" captures the mood better than the technically perfect shot.

The legacy of Chased by the Light isn't about being a hermit or being "anti-tech." It’s about intentionality. In a world that wants you to move faster, there is a profound, almost rebellious power in choosing to move slower. Jim Brandenburg proved that one single, well-considered moment is worth more than a thousand mindless clicks.

Next Steps for Your Own Practice:

To truly understand the weight of this method, pick a single subject near your home—a tree, a street corner, even a window. Commit to taking one photo of it every day at the exact same time for thirty days. Don't worry about the weather or the "quality." Just focus on the discipline of the single frame. By the end of the month, you’ll have a narrative of change that no single "perfect" photo could ever convey. This builds the "muscle memory" of seeing light rather than just subjects, which is the core secret that Brandenburg used to transform the North Woods into a masterpiece.