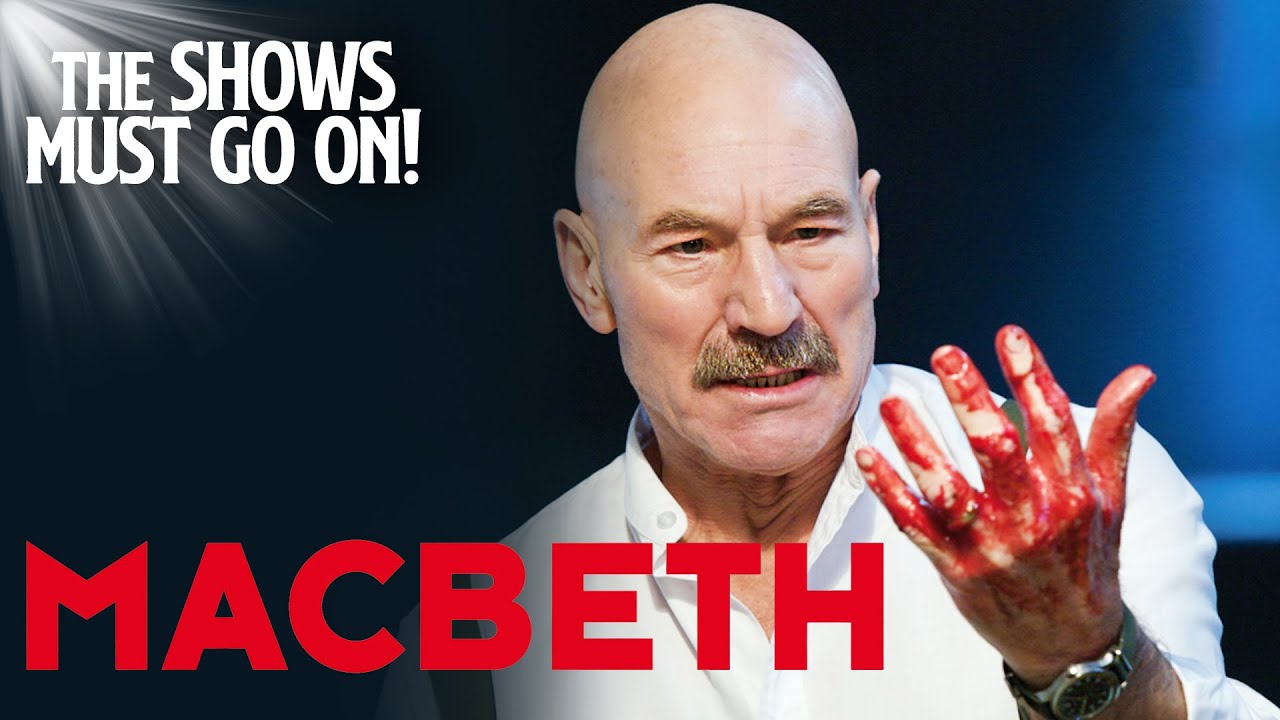

Shakespeare is often dusty. You know the vibe—guys in tights, fake sword fights, and actors shouting at the back of the room like they’re trying to wake up a sleeping usher. But then there’s the 2010 Patrick Stewart Macbeth.

It’s different. Honestly, it’s terrifying.

Directed by Rupert Goold, this isn't a "movie" in the traditional Hollywood sense, but a filmed version of the Chichester Festival Theatre production. It doesn't feel like a stage play, though. It feels like a fever dream set in a Stalinist bunker. If you’ve ever wondered what happens when you mix 17th-century prose with 20th-century totalitarians, this is your answer.

The Cold Reality of a Soviet Macbeth

Forget the Scottish Highlands. There are no rolling green hills here. Instead, Goold traps us in a subterranean world of white tiles, industrial kitchens, and flickering fluorescent lights. The setting is basically a brutalist nightmare.

Most of the "film" was shot at Welbeck Abbey, a massive country house in Nottinghamshire with a bizarre network of underground tunnels. It’s claustrophobic. You can almost smell the damp concrete and the stale cigarette smoke. By shifting the timeline to a sort of mid-century Soviet era, the stakes change. Macbeth isn't just a lord wanting a promotion; he’s a mid-level officer in a killing machine who decides to become the machine himself.

🔗 Read more: The Reality of Sex Movies From Africa: Censorship, Nollywood, and the Digital Underground

Patrick Stewart plays Macbeth as a man who has seen too much war. He’s tired. He’s competent. And when the opportunity for power arrives, he doesn't just "want" it—he consumes it.

There’s this one scene where he’s making a sandwich. Just a ham sandwich. But the way he handles the knife, the precision of the mustard—it’s more menacing than any battle scene. It shows a man who has completely compartmentalized the act of murder into a daily routine.

Why the Witches as Nurses Works

The "Weird Sisters" are usually the hardest part of Macbeth to get right. Do you make them literal hags? Goth teenagers? Goold turns them into hospital nurses.

It’s brilliant.

💡 You might also like: Alfonso Cuarón: Why the Harry Potter 3 Director Changed the Wizarding World Forever

Nurses are supposed to be healers. In this version, they are the ones who harvest hearts from the dying. They linger in the background of almost every scene, masquerading as servants or medical staff. They don't just predict the future; they seem to be actively dissecting the present.

- The Heart Scene: Right at the start, they pull a beating heart out of a wounded soldier. It sets the tone immediately: this isn't a fairy tale.

- The Kitchen: They aren't brewing potions in a cauldron; they’re grinding meat in a dingy kitchen.

- The Presence: Because they look like staff, they can go anywhere. They are the "surveillance state" personified.

Kate Fleetwood: The Real Power

You can't talk about the Patrick Stewart Macbeth without talking about Kate Fleetwood’s Lady Macbeth. She is ice-cold. While Stewart’s Macbeth slowly descends into a loud, frantic madness, Fleetwood’s descent is quiet and devastating.

Her "unsex me here" monologue is delivered with a visceral intensity that makes your skin crawl. She isn't just a "supportive wife" with a dark streak. She is the architect of their shared doom.

The chemistry between Stewart and Fleetwood is what makes the 2010 film feel so modern. They aren't just archetypes. They’re a middle-aged couple whose marriage is built on a foundation of shared trauma and lethal ambition. When she eventually breaks—the famous "out, damned spot" sleepwalking scene—it doesn't feel like a theatrical flourish. It feels like a psychiatric collapse.

📖 Related: Why the Cast of Hold Your Breath 2024 Makes This Dust Bowl Horror Actually Work

The Technical Wizardry of Rupert Goold

Goold uses the camera to mess with your head. There’s a heavy use of film noir aesthetics—lots of high-contrast lighting and deep shadows.

He also uses a cage elevator as a recurring symbol. It’s the literal and metaphorical "ascent" to power, but it feels like a prison. Every time characters step into that lift, you know something terrible is about to happen. It bridges the gap between the public life of the "state" and the private horror of the Macbeths' living quarters.

The film also kept a famous trick from the stage production. In the banquet scene where Banquo's ghost appears, we see it twice. Once through Macbeth’s eyes—where the ghost is physically there, horrifyingly real—and once from the perspective of the guests. In the second version, the seat is empty. It forces you to realize that Macbeth isn't just being haunted; he’s losing his grip on reality in front of everyone he needs to impress.

Is This Version for You?

If you want a traditional "period piece" with kilts and bagpipes, look elsewhere. Try the Roman Polanski version or the 2015 Justin Kurzel film.

But if you want a version that understands the psychology of a dictator, the 2010 Patrick Stewart Macbeth is the gold standard. It treats the text like a living, breathing thing rather than a museum artifact.

Actionable Takeaways for Viewing

- Watch it on a big screen with good sound. The sound design—industrial hums, dripping water, sudden screams—is half the experience.

- Pay attention to the background. The witches (nurses) are often hiding in plain sight. It’s like a "Where's Waldo" of impending doom.

- Notice the costumes. They transition from World War I style trench coats to more modern, polished military uniforms as Macbeth’s power grows. It’s a visual representation of his "Stalinization."

- Look for the sandwich. I'm serious. The sandwich scene is a masterclass in acting.

The Patrick Stewart Macbeth proves that you don't need a hundred-million-dollar budget to make a masterpiece. You just need a claustrophobic tunnel, a sharp knife, and an actor who knows exactly how to make a ham sandwich look like a death warrant.