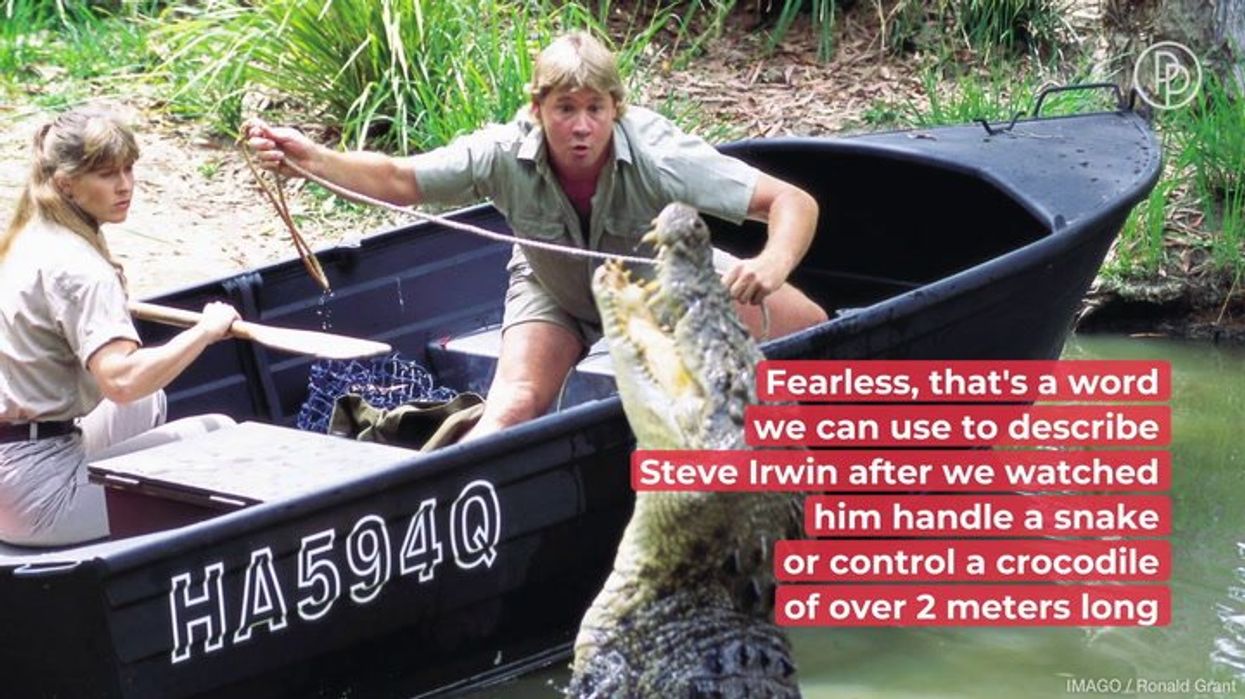

You're wading through knee-deep water, the sun is hitting your back, and you feel something soft under your foot. Most of the time, that "something" is just a patch of seaweed or a buried shell. But sometimes, it’s a flat, winged fish hiding under the sand. Getting killed by a stingray is, honestly, one of those freak occurrences that occupies a massive space in our collective nightmares despite being statistically almost impossible. We all remember where we were when Steve Irwin died in 2006. It felt like a glitch in the matrix because we’d watched him handle crocodiles and king cobras for years.

But here’s the reality: stingrays aren’t hunters. They aren’t looking for a fight. They are basically the "grumpy introverts" of the ocean floor. Most of the time, if you step on one, it just wants you to get off its back. It lashes out because it thinks it’s about to be eaten by a shark or a ray-eating predator. Understanding the mechanics of how these animals function—and why deaths are so incredibly rare—is the best way to lose the fear before your next beach trip.

The Biology of the Barb

A stingray isn't a single species. We’re talking about a group of rays consisting of eight different families, like the Dasyatidae (whiptail stingrays). Their "stinger" isn't actually at the tip of their tail like a scorpion. It’s a modified dermal denticle—essentially a giant, jagged tooth—located partway down the tail. This spine is covered in a thin layer of skin called the integumentary sheath. When the ray strikes, that skin breaks, and the venom glands underneath release a cocktail of proteins.

The venom itself is nasty. It’s "proteolytic," which is a fancy way of saying it breaks down tissue and causes intense, localized cell death. If you get hit in the foot, it’s going to hurt like nothing you’ve ever felt. People describe it as a hot iron being pressed into the skin. But venom alone is rarely what leads to someone being killed by a stingray. The real danger isn't the "poison"—it’s the plumbing.

Why Fatalities Are Anomalies

Most stingray injuries happen on the ankles or feet. You step on them, they whip their tail up, and you get a painful puncture wound. You go to the ER, they soak it in hot water to denature the protein-based venom, and you're fine in a few days. So, why do people actually die?

It almost always comes down to the location of the strike. In the case of Steve Irwin, the barb pierced his thoracic wall and entered his heart. When the barb is pulled out—or if it moves while inside—the serrated edges act like a saw. These barbs are designed to go in easy and stay in. They have backward-pointing teeth. If a barb enters a vital organ like the heart, lungs, or abdomen, the physical trauma and subsequent internal bleeding are the primary killers.

🔗 Read more: Why Amundsen-Scott South Pole Station is Much Weirder Than You Think

According to data from the California Poison Control System and various maritime medical records, there are only about 1,000 to 2,000 stingray injuries reported in the U.S. annually. Fatalities? Almost zero. Globally, the number of people killed by a stingray is estimated to be only one or two people per year. You are significantly more likely to die from a lightning strike or even a vending machine falling on you.

The Steve Irwin Effect and Public Perception

We can't talk about this topic without mentioning the "Crocodile Hunter." His death was a "black swan" event. He was filming a documentary called Ocean's Deadliest and happened to be swimming over a large bull ray. The ray, likely feeling cornered, struck hundreds of times in a few seconds. One of those strikes hit perfectly between the ribs.

What’s interesting is that Irwin actually pulled the barb out. Medical experts often debate whether staying still and leaving the object in place might have changed the outcome, but with a direct puncture to the heart, the odds were astronomical anyway. This single event changed how the world viewed rays. Before 2006, they were seen as gentle "birds of the sea." Afterward, beachgoers started looking at the sand with a lot more suspicion.

But you have to remember: he was intentionally interacting with wildlife in a way most of us never will. For the average snorkeler or swimmer, the risk remains negligible.

The Venom Chemistry

Let's get into the weeds for a second. Stingray venom contains 5-nucleotidase and phosphodiesterase. These enzymes cause the rapid breakdown of tissues. It also contains serotonin, which is why the pain is so immediate and agonizing—serotonin causes smooth muscle contraction and intense nerve firing.

💡 You might also like: Weather San Diego 92111: Why It’s Kinda Different From the Rest of the City

If you are stung, the goal isn't just to stop the pain. You’re fighting a two-front war:

- The Physical Trauma: Is there a piece of the barb left in there?

- The Bio-Hazard: Stingrays live in the mud. Their barbs are covered in bacteria like Vibrio vulnificus.

Secondary infections are actually a bigger threat to life and limb than the venom itself for most people. If a sting goes untreated, necrotizing fasciitis (flesh-eating bacteria) can set in. That’s why "home remedies" besides hot water are a bad idea. You need a professional to irrigate the wound.

Myths vs. Reality

One common myth is that stingrays "attack" people. They don't. They have no interest in you. They eat mollusks, crustaceans, and small fish. You are a giant, vibrating mountain that might step on them. Their only defense is that tail.

Another misconception is that all rays sting. Manta rays, for example, are enormous and look intimidating, but they don't even have a stinger. They are filter feeders. You could swim with a Manta Ray all day and the only danger you'd face is getting accidentally bumped by a few tons of fish.

How to Not Get Stung (The Stingray Shuffle)

If you're worried about being killed by a stingray, or even just getting a painful poke, there is one foolproof method to stay safe. It’s called the "Stingray Shuffle."

📖 Related: Weather Las Vegas NV Monthly: What Most People Get Wrong About the Desert Heat

Don't lift your feet when you walk in the water. Slide them. If you shuffle your feet along the bottom, you’ll bump into the side of the ray. This gives it a "heads up" and it will almost always just flutter away. They only sting when they feel pinned down from above. If you kick them from the side, they just think you're a clumsy neighbor and they move out of the way.

What to Do If the Worst Happens

If you or someone you’re with gets hit, don’t panic. Panic increases your heart rate, which spreads venom faster (though, again, the venom isn't usually the "deadly" part).

- Check the location. If it’s in the chest or abdomen, do not move. Call emergency services immediately. Do not pull the barb out if it's deep in the torso.

- Heat is your friend. Immerse the wound in the hottest water you can tolerate (without burning yourself). This breaks down the venom’s proteins and kills the pain almost instantly.

- Antibiotics are mandatory. Because of the bacteria mentioned earlier, you need a course of antibiotics. Even a "minor" sting can turn into a nightmare if Vibrio gets a foothold.

Real-World Stats and Safety

In places like Stingray City in the Cayman Islands, thousands of tourists handle and feed Southern Stingrays every single day. These rays have become habituated to humans. They are like underwater puppies. While accidents can happen, the lack of fatalities in these high-traffic areas proves that these animals are not inherently aggressive.

The vast majority of deaths involving stingrays in history have involved the barb entering the heart, the neck, or causing a severe allergic reaction (anaphylaxis), which is even rarer than the stings themselves.

Quick Safety Checklist

- Shuffle your feet. Every time. No exceptions.

- Wear thick-soled booties. They aren't foolproof, but they can deflect a glancing blow.

- Watch the tides. Rays love shallow, warm water during high tide.

- Respect the distance. If you see one, give it a few feet of space.

Stingrays are a vital part of the ocean's ecosystem. They stir up the sand, uncovering food for smaller fish. They are beautiful, graceful, and mostly misunderstood. Being killed by a stingray is a tragic, lightning-strike event that shouldn't stop you from enjoying the ocean. Just remember that you’re a guest in their living room.

Next Steps for Ocean Safety

If you're heading to a beach known for ray activity (like the Gulf Coast or Southern California), buy a pair of puncture-resistant wading boots. Also, carry a small thermos of hot water in your car—it's the only thing that truly neutralizes the pain if a sting occurs. Always check with local lifeguards about "purple flag" warnings, which often indicate dangerous sea life in the area.