If you’re staring at a graph with two crossing lines and feeling like your brain is melting, welcome to the club. Honestly, AP Macroeconomics Unit 3 is where most students realize that this isn't just about "supply and demand" for lemonade stands anymore. This is the big stuff. We're talking about the entire economy—national income, price levels, and why the government keeps messing with your taxes.

Think of it this way. Unit 1 and 2 were just setting the table. Unit 3 is the actual meal. It’s where the Aggregate Demand and Aggregate Supply (AD-AS) model takes center stage. If you don't get this, the rest of the exam is basically a lost cause. But if you do? You’re golden.

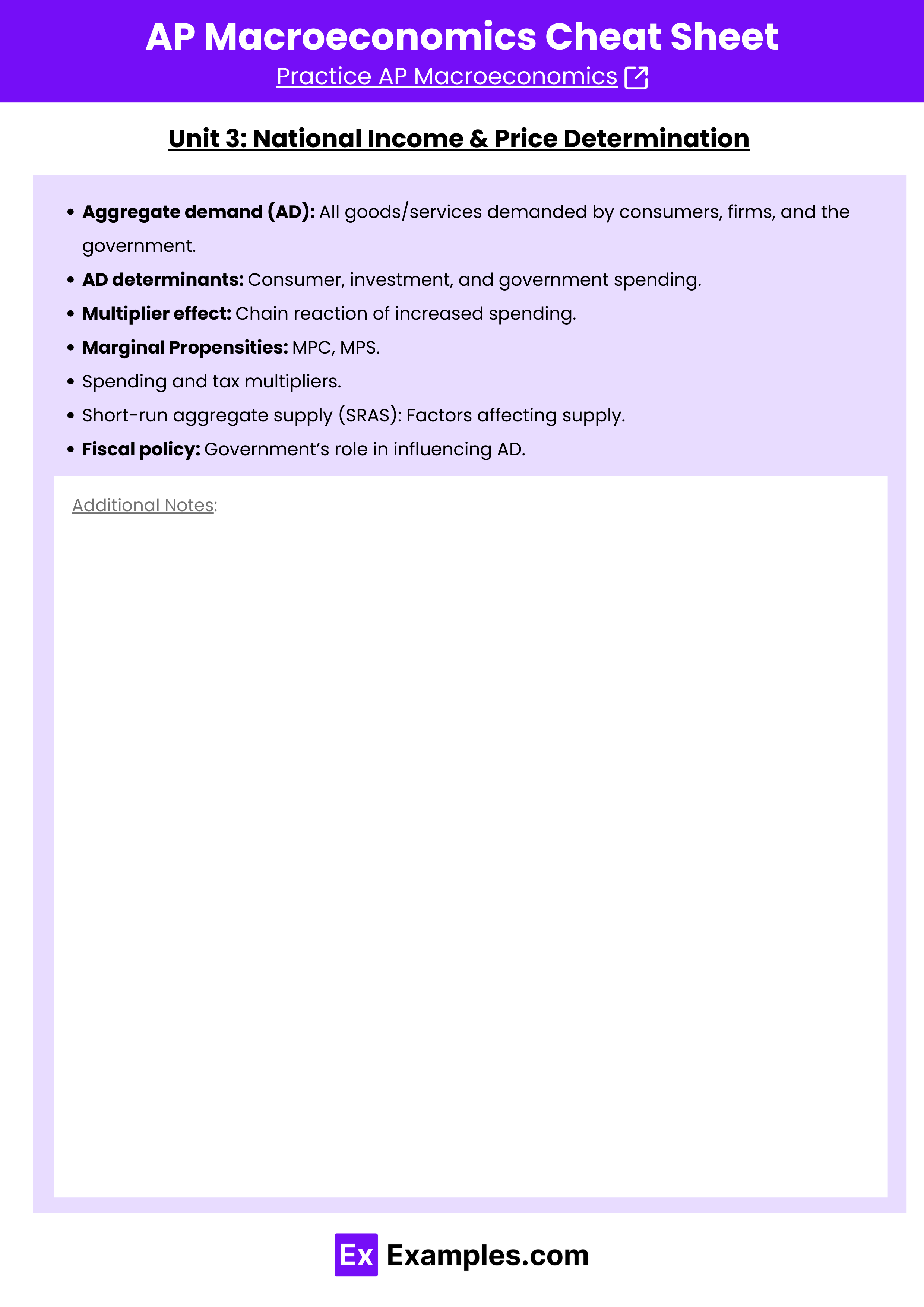

The AD-AS Model Is Basically the Ruler of Everything

So, what is AP Macroeconomics Unit 3 actually about? It’s the study of National Income and Price Determination. In plain English, it's how we figure out if a country is rich, poor, or currently spiraling into a recession.

The heart of it is the AD-AS model. You've got Aggregate Demand (AD), which is just a fancy way of saying "how much stuff does everyone in the country want to buy?" Then you have Aggregate Supply (AS). That’s "how much stuff are businesses actually making?"

Here is the kicker: Aggregate Supply is split into two parts. You have the Short-Run Aggregate Supply (SRAS) and the Long-Run Aggregate Supply (LRAS). If you forget the difference between these on the FRQ, you're toast. Short-run is sticky. Prices and wages don't change instantly. Long-run is flexible. It’s the "potential" of the economy. It’s a vertical line because, in the long run, our ability to produce stuff depends on resources and tech, not just the price of a burger.

Why Does the AD Curve Slope Down? (Hint: It’s Not Just "Law of Demand")

In Unit 1, the demand curve sloped down because if tacos get cheaper, you buy more tacos. Simple. In Unit 3, it’s different. We are talking about the entire economy. You can't just switch from buying "everything" to "nothing."

✨ Don't miss: Georgia Apply for Unemployment: What Most People Get Wrong

There are three specific reasons the AD curve slopes downward, and you've gotta know them by name:

- The Wealth Effect: When price levels drop, the cash in your pocket is suddenly worth more. You feel richer. You buy more stuff.

- Interest Rate Effect: Lower prices mean people save more. Banks have more money to lend. Interest rates drop. Businesses borrow money to buy machines. Boom—investment spending goes up.

- Foreign Purchases Effect: If American goods get cheaper compared to European goods, people in France buy our stuff (Exports up) and we buy less of theirs (Imports down).

If you see a question about why the AD curve shifts, remember the formula: $GDP = C + I + G + (X - M)$. If anything in that equation changes—like consumer confidence or a new government spending bill—the whole curve moves.

The Multiplier Effect: Turning $1 Into $5

This is where it gets kinda weird. If the government spends $100 billion on new bridges, the economy doesn't just grow by $100 billion. It grows by way more. Why? Because the people who built the bridge now have money. They spend it at the grocery store. The grocer then spends it on a new car.

This is the Multiplier Effect.

To calculate it, you need the Marginal Propensity to Consume (MPC). If you get a $100 bonus and spend $80, your MPC is 0.8. Your Marginal Propensity to Save (MPS) is 0.2.

The formula is simple: $1 / MPS$.

So, if the MPS is 0.2, the multiplier is 5. That $100 billion in government spending actually turns into $500 billion of total economic activity. It sounds like magic. It’s actually just math.

Fiscal Policy: The Government's Toolkit

When the economy is in a recession (a "recessionary gap"), the government tries to kickstart it. They use Expansionary Fiscal Policy. They can either increase spending or decrease taxes.

But wait. There's a catch.

Tax cuts are less powerful than spending increases. Why? Because when the government spends money, 100% of it enters the economy immediately. When they cut taxes, people save a little bit of that money. So, the "Tax Multiplier" is always one less than the "Spending Multiplier" and it's negative.

$Tax Multiplier = -MPC / MPS$.

The Long Run is a Different Beast

Most students struggle with the "Self-Correction" mechanism. Let's say we are in an inflationary gap. Prices are high. Unemployment is low. In the short run, we’re partying. But eventually, workers realize their paychecks don't buy as much as they used to. They demand higher wages.

As wages rise, it gets more expensive for businesses to make stuff. The SRAS curve shifts to the left. Eventually, we end up back at the LRAS line, but with much higher prices. This is why economists like Milton Friedman argued that the government should often just stay out of it. Of course, John Maynard Keynes famously quipped, "In the long run, we are all dead."

Common Pitfalls to Avoid on the Exam

Don't mix up a movement along the curve with a shift of the curve. A change in the price level only moves you along the AD or SRAS line. It does not shift them.

Also, watch out for the "Crowding Out" effect. This happens when the government borrows a ton of money to fund spending. This drives up interest rates. High interest rates make it too expensive for private businesses to borrow money. So, government spending "crowds out" private investment. It’s like the government is taking all the seats at the table and leaving no room for anyone else.

Real World Nuance: It’s Not Always a Perfect Graph

In a textbook, the SRAS curve is a nice, neat slope. In the real world, things are messy. We have supply shocks—like the oil crisis in the 70s or the supply chain chaos in 2021. These cause Stagflation. This is the worst-case scenario: prices go up (inflation) and output goes down (recession).

Standard fiscal policy usually can't fix stagflation easily. If you increase spending to fix the unemployment, you make the inflation worse. If you cut spending to fix inflation, you make the unemployment worse. It's a nightmare for policymakers.

📖 Related: Yanni Hufnagel and Lemon Perfect: What Really Happened

Actionable Steps for Mastering Unit 3

If you want to ace the Unit 3 section of the AP Macroeconomics exam, stop just reading and start drawing.

- Draw every scenario: Practice drawing a recessionary gap, an inflationary gap, and full employment at least five times each.

- Memorize the Multipliers: You cannot afford to fumble the math on $1/MPS$. It is the easiest point you will get on the exam if you know it.

- Identify the "Shifters": Make a list of what moves AD (C, I, G, Xn) and what moves SRAS (RAP: Resources, Actions of Gov, Productivity).

- Connect to Unit 4: Start thinking about how the Federal Reserve fits in. Unit 3 is about fiscal policy (Congress), but Unit 4 is about monetary policy (The Fed). They often work together—or against each other.

By focusing on the AD-AS equilibrium and the relationship between the price level and real GDP, you'll bridge the gap between simple supply/demand and the complex machine that is a national economy.