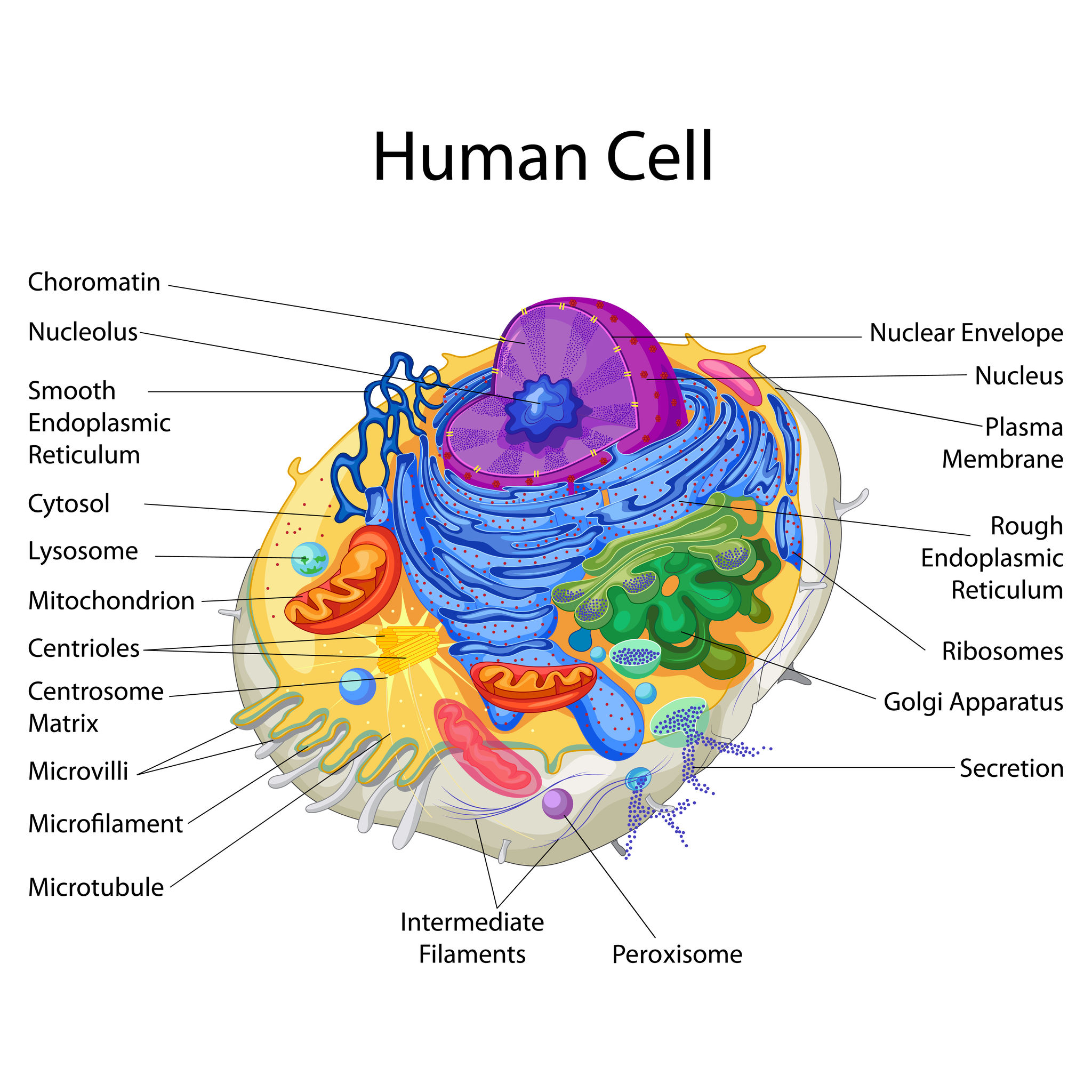

You probably remember the poster from middle school. It was bright, maybe a bit neon, and featured a lumpy oval that looked suspiciously like a cross-section of a bean or a jelly donut. That was your introduction to the cell. But honestly, most of those posters are kind of a lie. When you look at a labeled diagram of a cell, you’re seeing a frozen, simplified snapshot of something that is actually a chaotic, crowded, and pulsing city. It’s not a bag of soup with some floating bits. It’s an architectural masterpiece that’s constantly tearing itself down and building itself back up.

Biology is messy.

Real cells aren't transparent. They are packed so tightly with proteins and organelles that there is barely room for water to move. If you actually saw a high-resolution electron micrograph of a human cell, you might not even recognize the parts you spent hours memorizing for a quiz.

What a Labeled Diagram of a Cell Usually Gets Wrong

Most diagrams show the nucleus as this big, purple ball in the center. While the nucleus is the "brain," it isn't always in the middle. In some cells, it’s shoved to the side to make room for other things. For example, in a fat cell (an adipocyte), the giant droplet of stored fat is so huge it literally squashes the nucleus against the cell membrane.

Then there’s the cytoplasm. Diagrams make it look like empty space. It's not. It is a dense "cytosol" filled with a cytoskeleton that acts like a combination of a highway system and a structural scaffold. Without this, your cells would just collapse into a puddle of molecular goop.

The Nucleus: More Than Just a Library

The nucleus holds your DNA. We know this. But a labeled diagram of a cell often misses the nuclear pores. These are the gatekeepers. Imagine a club with the strictest bouncers in the world. Only specific proteins and RNA molecules are allowed in or out. The DNA itself never leaves; it’s too precious. Instead, it sends out "photocopies" in the form of mRNA.

Inside the nucleus, you’ll see the nucleolus. It’s the dark spot. This is where ribosomes are born. If the cell is a factory, the nucleolus is the department that builds the machines that build the products. It’s remarkably efficient.

💡 You might also like: Foods to Eat to Prevent Gas: What Actually Works and Why You’re Doing It Wrong

Mitochondria: The Powerhouse Meme

Everyone says it. "The mitochondria is the powerhouse of the cell." It's a cliché because it's true, but diagrams often fail to show how dynamic they are. Mitochondria aren't static little sausages. They fuse together into long networks and then break apart again. They have their own DNA, which is weird when you think about it. This is a remnant of an ancient event where one single-celled organism basically ate another, and instead of digesting it, they decided to live together forever.

The Logistics Hub: ER and Golgi

If you follow a labeled diagram of a cell outward from the nucleus, you hit the Endoplasmic Reticulum (ER). It looks like a stack of flattened pancakes or a maze.

The "Rough" ER is covered in ribosomes, which makes it look bumpy. These ribosomes are cranking out proteins. The "Smooth" ER is where lipids (fats) are made and where toxins are neutralized. If you drink a glass of wine, the smooth ER in your liver cells goes into overdrive to process that alcohol.

Then comes the Golgi Apparatus. Think of this as the FedEx or UPS hub. It receives proteins from the ER, puts "shipping labels" on them (usually by adding sugar molecules), and packs them into vesicles to be sent to their final destination. Without the Golgi, your proteins would just wander around the cell with nowhere to go.

The Garbage Disposal: Lysosomes and Peroxisomes

Cells create waste. A lot of it. Lysosomes are the recycling centers. They are filled with digestive enzymes that can break down almost anything—bacteria, old organelles, or misfolded proteins. If a lysosome leaks, it can actually start digesting the cell itself. It's a dangerous but necessary part of the ecosystem.

Peroxisomes are similar but specialized. They deal with oxidative reactions and break down fatty acids. They produce hydrogen peroxide as a byproduct, which is toxic, so they also contain an enzyme called catalase to turn that peroxide into harmless water and oxygen. It’s a delicate chemical balancing act.

📖 Related: Magnesio: Para qué sirve y cómo se toma sin tirar el dinero

Why Scale Matters in Cell Diagrams

One thing a labeled diagram of a cell almost never captures is the sheer scale of the molecules inside.

A protein is tiny compared to a mitochondrion. If a cell were the size of a large city, a protein would be about the size of a human, and the nucleus would be a massive skyscraper complex in the center. The "empty" space between organelles is actually filled with millions of these protein "humans" rushing around to do their jobs.

- Microtubules: These are the heavy-duty structural beams.

- Actin filaments: These help the cell move and change shape.

- Intermediate filaments: These provide the tensile strength so your cells don't snap when you stretch.

The Membrane: The Velvet Rope

The cell membrane isn't just a skin. It’s a "fluid mosaic." It’s made of phospholipids that are oily and move around like people in a crowded room. Floating in this oil are proteins that act as sensors, channels, and pumps.

This is where the cell interacts with the world. Receptors on the surface pick up signals like hormones or nutrients. If you take a medication like ibuprofen, it works by interacting with specific proteins on or near these membranes.

Plant vs. Animal: The Big Differences

When looking at a labeled diagram of a cell, you have to know if you're looking at a plant or an animal.

- Cell Wall: Only plants (and fungi/bacteria) have this. It’s a rigid outer layer made of cellulose. It’s why trees can grow tall without a skeleton.

- Chloroplasts: These are the green bits in plants. They turn sunlight into sugar. Like mitochondria, they have their own DNA.

- Large Central Vacuole: Plants have a massive water balloon in the middle. It provides "turgor pressure." When you forget to water your plants and they wilt, it’s because this vacuole has emptied out and the cell is collapsing inward.

How to Study a Labeled Diagram of a Cell Without Going Crazy

Don't just stare at the picture. That doesn't work for most people.

👉 See also: Why Having Sex in Bed Naked Might Be the Best Health Hack You Aren't Using

Instead, try to trace the "life of a protein." Start at the DNA in the nucleus. Move to the ribosome on the Rough ER where it’s built. Follow it to the Golgi where it gets tagged. Watch it get loaded into a vesicle and shipped out through the cell membrane.

If you can tell that story, you actually understand the diagram. You aren't just memorizing labels; you're understanding a process.

Real-World Applications: Why Should You Care?

Understanding cell structure isn't just for passing a test. It’s the foundation of modern medicine.

Cancer is basically what happens when the "instruction manual" in the nucleus gets a typo and the cell starts dividing uncontrollably. Many antibiotics work by attacking the specific structure of a bacterial cell wall—something human cells don't have—so the medicine kills the bacteria but leaves you alone.

Viral infections, like the flu or COVID-19, happen because a virus hijacks the cell’s own machinery (the ribosomes and ER) to make copies of itself. When you look at a labeled diagram of a cell, you are looking at the battlefield where your immune system fights every day.

Take Action: How to Master Cell Biology

To truly grasp these concepts, stop looking at 2D drawings and explore 3D visualizations.

- Use Interactive Tools: Websites like Cell SALIVE! or the Harvard BioVisions videos (like "The Inner Life of the Cell") show these structures in motion. Seeing a kinesin motor protein "walk" along a microtubule is a game-changer for your understanding.

- Draw It Yourself: Don't just print a diagram. Draw it. Label it. Use different colors for the "shipping" parts of the cell versus the "power" parts.

- Compare and Contrast: Look at diagrams of specialized cells, like a neuron or a muscle cell. See how they modify the basic "bean" shape to fit their specific function. Neurons have long axons for communication; muscle cells are packed with mitochondria for energy.

The cell is the smallest unit of life, but it’s arguably the most complex thing in the universe. Once you move past the static labels and see the moving parts, biology starts to make a lot more sense. Focus on the relationships between the organelles—how the nucleus talks to the ER, and how the Golgi feeds the membrane. That's where the real science happens.