You’ve probably heard the name Zora Neale Hurston. Maybe you read Their Eyes Were Watching God in a high school English class, or you've seen those black-and-white photos of her in a jaunty hat, looking like she’s about to tell a joke that’ll make the whole room roar. But if you really want to get her—like, actually understand why she wrote the way she did—you have to look at a tiny dot on the map just north of Orlando.

Zora Neale Hurston and Eatonville Florida are basically two sides of the same coin.

Most folks think she was born there. She wasn't. She was actually born in Notasulga, Alabama, in 1891. But she never claimed Alabama. To Zora, Eatonville was the "center of the world." It was the first all-Black incorporated town in the United States, and that single fact changed everything for her. Imagine growing up in a place where the mayor, the marshal, and the shopkeepers all looked like you. No "whites only" signs. No looking down at your shoes when a white person walked by. In Eatonville, Zora was just Zora.

The Town That Freedom Built

Eatonville isn't just a setting in a book; it’s a real place with a wild history. Back in the 1880s, a group of Black men wanted a town of their own. They tried to buy land, but white landowners kept saying no. Finally, a white captain named Josiah Eaton and a philanthropist named Lewis Lawrence sold them the acreage. On August 15, 1887, twenty-seven Black men met and voted to incorporate.

Zora’s dad, John Hurston, was one of those men. He was a carpenter and a preacher, and he eventually served three terms as mayor.

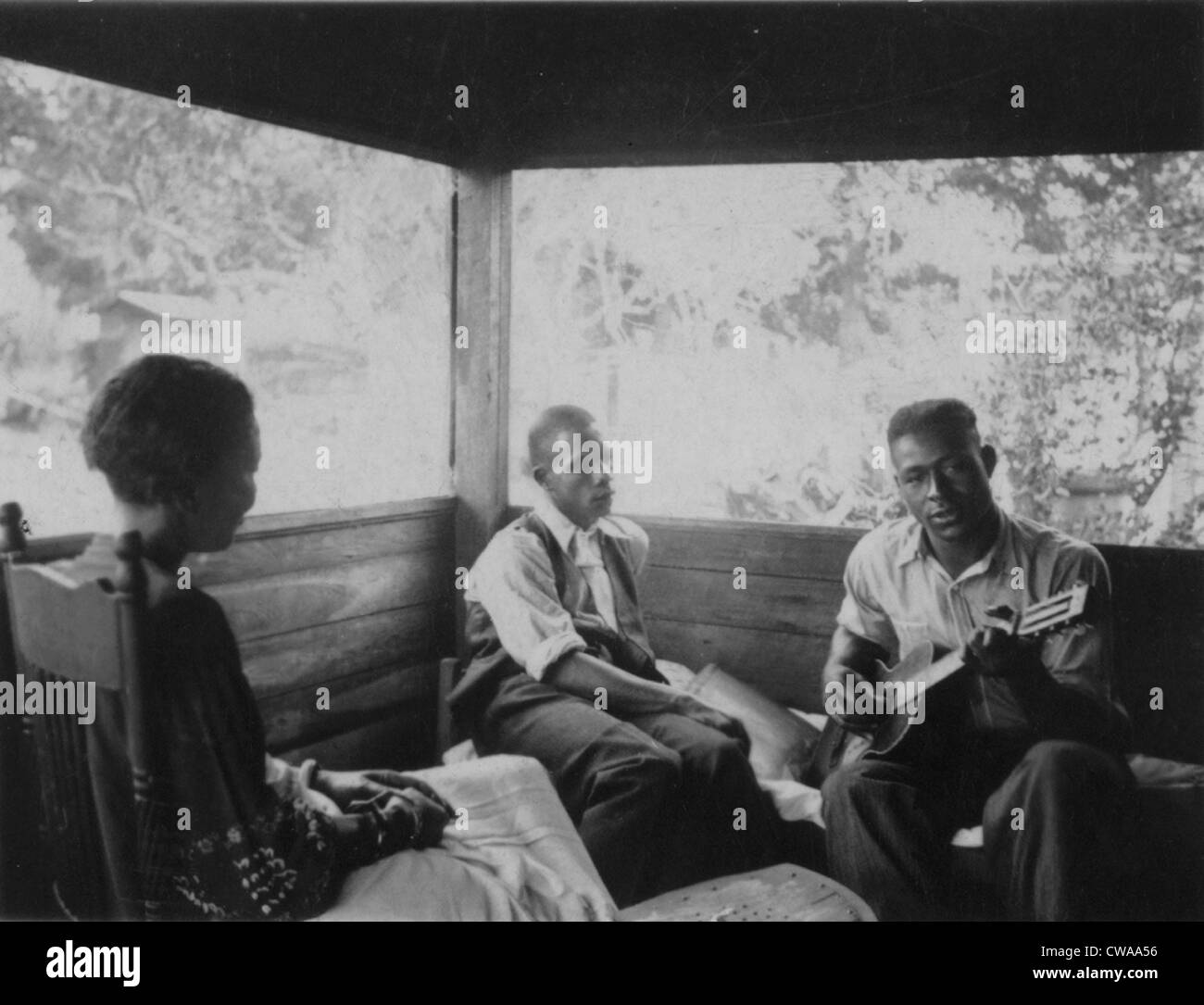

That’s why Zora’s writing feels so confident. She wasn't writing about "the struggle" in the way many of her Harlem Renaissance peers were. She was writing about Black life as the default. To her, Black culture wasn't a reaction to white supremacy; it was its own vibrant, beautiful, messy thing. She spent her childhood sitting on the porch of Joe Clarke’s general store, listening to the men "lying"—that’s what they called telling tall tales. Those stories became the backbone of her career as an anthropologist and a novelist.

Why the Porch Mattered

If you visit Eatonville today, you won’t see that original store, but the spirit of "the porch" is everywhere. To Zora, the porch was a stage.

👉 See also: Why the Man Black Hair Blue Eyes Combo is So Rare (and the Genetics Behind It)

- It was where folklore was born.

- It was where the community held its trials and celebrations.

- It was where she learned that language could be a weapon or a gift.

She once described Eatonville as a city of "five lakes, three croquet courts, three hundred brown skins, three hundred good swimmers, plenty guavas, two schools, and no jailhouse." Honestly, it sounds like a dream. But it wasn't a utopia. It was a real town with real problems, and she didn't shy away from that either.

The Tragic Gap and the "Haunted Years"

Things went south for Zora when she was thirteen. Her mother, Lucy Potts Hurston, died in 1904. Lucy was the one who told Zora to "jump at de sun." Her father remarried quickly—to a woman Zora absolutely loathed—and suddenly, the girl who was the "mayor's daughter" was being shunted from relative to relative.

She called the decade after her mother’s death her "haunted years."

She worked as a maid, a manicurist, and whatever else she had to do to survive. She even lied about her age to get into high school for free. She told the school she was sixteen when she was actually twenty-six. It worked. She kept that lie going for the rest of her life, which is kind of hilarious and very Zora. She wasn't going to let a little thing like a birth certificate stop her from getting an education.

The Harlem Renaissance and the Return Home

By the 1920s, she was in New York, the life of the party during the Harlem Renaissance. She was friends with Langston Hughes and studied under the "father of American anthropology," Franz Boas, at Barnard. But New York wasn't enough. Boas sent her back to the South to collect folklore.

Where did she go first? You guessed it.

✨ Don't miss: Chuck E. Cheese in Boca Raton: Why This Location Still Wins Over Parents

She rolled into Eatonville in a fancy car, wearing expensive clothes, and realized her old friends wouldn't talk to her if she acted like a big-city intellectual. So, she ditched the "Barnard" accent and just became Zora again. She collected songs, stories about "Old Massa" and "John," and details about Voodoo (or Hoodoo) that nobody else was getting.

She realized that the way people talked in Eatonville was art. While other writers were trying to make Black characters sound "proper" to impress white readers, Zora leaned into the dialect. She wanted you to hear the rhythm of the porch.

The Hurston Museum and Saving the Town

Fast forward to the late 1980s. Eatonville was in trouble. Developers wanted to run a big five-lane road right through the heart of the town. It would have leveled the historic district.

But then, the community fought back. They used Zora’s legacy as a shield. They formed the Association to Preserve the Eatonville Community (P.E.C.) and started the Zora! Festival. Suddenly, this tiny town was an international destination for scholars and fans.

Today, you can visit the Zora Neale Hurston National Museum of Fine Arts. It’s not a huge, sprawling building like the Met, but it’s powerful. It focuses on artists of African descent, keeping Zora’s mission alive by giving a platform to voices that are often ignored.

What People Get Wrong About Her End

There’s this persistent narrative that Zora’s life was a tragedy because she died poor in 1960. She was working as a maid again and was buried in an unmarked grave in Fort Pierce.

🔗 Read more: The Betta Fish in Vase with Plant Setup: Why Your Fish Is Probably Miserable

But "poor" doesn't mean "failed."

Zora lived exactly how she wanted. She was fiercely independent. She didn't want to be a "professional Negro" or a political pawn. She ruffled feathers—like when she spoke out against the Brown v. Board of Education decision. Not because she liked segregation, but because she feared that losing Black schools would destroy Black culture and the sense of community she found in Eatonville. She was complicated.

It wasn't until 1973, when Alice Walker (author of The Color Purple) went looking for her grave, that the world started paying attention again. Walker bought her a headstone that calls her a "Genius of the South."

Actionable Ways to Experience Zora’s Eatonville

If you’re a fan or just curious, don't just read the books. Experience the place.

- Attend the ZORA! Festival: Usually held in late January, it’s a mix of academic talks, heavy-hitting jazz, and incredible food. It’s when the town really comes alive.

- Take the Walking Tour: There are sixteen historic markers in town that link Zora’s writing to specific spots. You can literally walk through the pages of her autobiography, Dust Tracks on a Road.

- Visit the Moseley House Museum: This is one of the oldest structures in town and gives you a real sense of what middle-class Black life looked like in the early 1900s.

- Read the "Other" Books: Everyone knows Their Eyes Were Watching God, but check out Mules and Men. It’s her collection of Eatonville folklore, and it’s basically a transcript of those porch conversations.

Eatonville today is still a small town. It’s got no grocery store and no gas station, just a Family Dollar and a lot of history. It’s struggling, like many historic places, but the pride there is thick. When you stand on the street, you realize Zora Neale Hurston didn't just write about a place—she was the product of a community that refused to be anything other than itself.

To understand the writer, you have to stand in her dust.

Go to Eatonville. See the lakes. Hear the stories. You'll realize that Zora never really left; she just made sure the rest of us would never forget where she came from. The next time you pick up one of her books, remember that every word was filtered through the Florida sun and the voices of the people who built a town where they could finally breathe free.