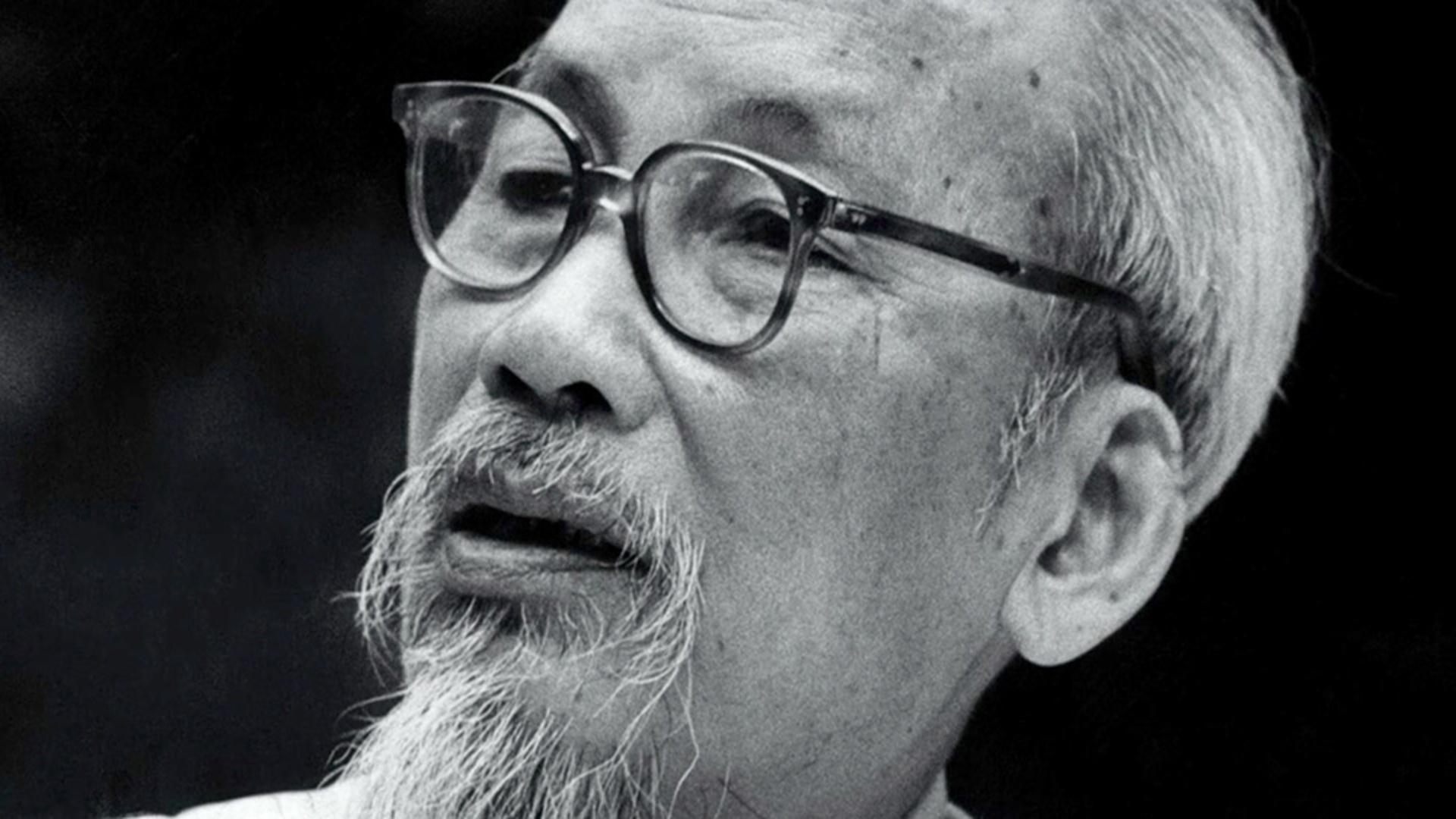

You’ve probably seen the posters. The wispy beard, the simple rubber sandals, the stoic "Uncle Ho" persona that defined a revolution. But before he was the face of North Vietnam, he was just a kid named Nguyen Sinh Cung, wandering the streets of Brooklyn and London, basically trying to figure out how to pay rent.

Most history books treat him like a statue that was born revolutionary. Honestly, that’s just not true. The young Ho Chi Minh wasn't a Communist mastermind from day one. He was a curious, slightly desperate, and incredibly hardworking young man who spent thirty years in exile doing jobs that would make most modern influencers quit in a heartbeat.

We’re talking about a guy who scrubbed pots, shoveled coal, and allegedly made the best dinner rolls in Boston.

The Cook’s Assistant Who Wanted to See the World

In 1911, the world was changing, but Vietnam was stuck. It was French Indochina back then, and if you were a bright kid with a bit of ambition, your options were pretty much "work for the French" or "fight the French."

Nguyen Tat Thanh (one of his many, many early names) chose a third option: he left.

He didn't leave as a diplomat. He signed up as a kitchen hand on a French merchant steamer called the Amiral Latouche-Tréville. His name on the manifest? "Van Ba." He was 21 years old.

Think about that for a second. He left his family and his country with almost no money. He spent months on the ocean, doing the kind of back-breaking labor that most people today only see in historical dramas. He wasn't just "traveling." He was observing. He saw the ports of Marseille, African colonies like Djibouti and Oran, and eventually, the skyline of New York City.

What did he actually do in America?

There’s a lot of myth-making here. Some people claim he worked for General Motors, but there’s zero proof of that. What we do know is that he spent time in Harlem and worked at the Omni Parker House in Boston.

If you’ve ever had a Parker House roll—those buttery, folded pieces of heaven—you might have a connection to the young Ho Chi Minh. He was a pastry assistant there between 1912 and 1913. Imagine the future leader of a revolution perfecting a lemon meringue pie while watching wealthy Americans dine.

He also spent a lot of time at the Boston Public Library. He wasn't just reading cookbooks; he was reading the U.S. Declaration of Independence. That’s where the "all men are created equal" stuff really started to stick in his head.

The London Fog and the Shadow of Versailles

By 1914, he’d moved to London. It was the height of the British Empire.

Life wasn't exactly glamorous. He worked as a snow sweeper (yeah, literally) and eventually landed a job at the Carlton Hotel. Legend says he trained under the world-famous chef Auguste Escoffier. While some historians debate how close they actually were, the hotel records do show a "Nguyen" working in the kitchens.

Why London mattered

London was where he started to get political. He joined the "Overseas Workers’ Association." He was starting to realize that the poverty he saw in London's East End wasn't that different from the poverty in Vietnam.

Then came 1919. The "Big Bang" moment for his political career.

The Great War was over. World leaders were gathered at Versailles to redraw the map of the world. President Woodrow Wilson was talking about "self-determination." The young Ho Chi Minh, now calling himself Nguyen Ai Quoc (Nguyen the Patriot), rented a tuxedo, hopped on a train to Versailles, and tried to hand a petition to the world’s most powerful men.

He wanted basic rights for the Vietnamese people. Not even full independence yet—just things like freedom of the press and the right to travel.

The world leaders ignored him.

That was the turning point. He realized that the "West" wasn't going to save Vietnam. If he wanted change, he had to find a different path.

Becoming "The Patriot" in Paris

Paris in the 1920s was wild. Hemingway was there. Picasso was there. And so was this thin Vietnamese guy working as a photo retoucher.

He spent his days fixing old photographs and his nights writing for Le Paria (The Outcast), a newspaper for people from the French colonies. He was living in a tiny, unheated room, surviving on bread and a few vegetables.

He joined the French Socialist Party, mostly because they were the only ones who seemed to care about colonial issues. But he eventually got frustrated with their "all talk, no action" vibe.

In 1920, he read Lenin’s "Theses on the National and Colonial Questions."

Supposedly, he was so moved by it that he cried in his room, shouting, "Dear martyrs, compatriots! This is what we need, this is the path to our liberation!"

From that moment on, he wasn't just a patriot. He was a revolutionary. He helped found the French Communist Party. He moved to Moscow. He went to China to train other Vietnamese exiles. He was a man with a mission, and he had the scars and the resumes to prove it.

Why the Young Ho Chi Minh Still Matters

It’s easy to look at the Vietnam War and see two-dimensional figures. But when you look at the young Ho Chi Minh, you see someone remarkably relatable.

He was a migrant worker. He was an immigrant. He was a guy who worked "gig economy" jobs a century before they had a name for it. He learned English, French, Chinese, and Russian because he had to survive.

He wasn't a "born" leader. He was forged by the rejection he felt at Versailles and the poverty he saw in London and New York.

Actionable Insights from his Early Life:

- Curiosity is a weapon. He didn't just stay in his bubble. He traveled to the heart of the empires that oppressed his people to see how they worked.

- Skill stacking works. Being a pastry chef, a photo retoucher, and a sailor gave him a unique perspective on how the world’s "gears" actually turn.

- Patience is everything. He spent 30 years outside of Vietnam. 30 years! Most people give up on their dreams if they don't see results in 30 days.

If you ever find yourself in Boston, stop by the Omni Parker House. Look at the kitchen. Think about the young man who was there, decades before the world knew his name, making rolls and dreaming of a country he hadn't seen in years.

To really understand the history of Southeast Asia, you have to start with the young Ho Chi Minh. You have to see the man before the myth. If you're interested in more historical deep dives, you should check out the archives of the Wilson Center or William Duiker’s biography, which is basically the gold standard for this stuff.