It was 1964. The Beatles were basically camping out at the top of the Billboard charts. Everyone wanted to hold someone’s hand. Then came Lesley Gore. She was 17. She had already sang about crying at her own party and how Judy had "turned" to cry. But then, she dropped a bombshell that sounded nothing like the bubblegum pop of the era. You Don’t Own Me wasn't just a hit; it was a line in the sand.

Honestly, it’s wild to think about. In an era where most "girl group" songs were about pining for boys or being "owned" by a boyfriend, Gore stood her ground. She looked right into the camera on The Ed Sullivan Show and told the world she wasn't a toy. She wasn't just another pretty thing to be put on display.

The Accidental Revolutionaries

You’d think a song this empowering was written by a coven of feminist icons, right? Nope. It was actually written by two guys from Philadelphia: John Madara and David White. They were the same duo behind "At the Hop." They weren't trying to start a political movement. They just wanted to write a song about a woman telling a guy off.

They met Lesley Gore at a hotel in the Catskills. She was there for a record hop. They played the song for her in a poolside cabana on a baritone ukulele. Gore loved it immediately. She saw something in the lyrics that felt like... well, like her.

Why the Song Felt So Different

Most pop songs back then were about "belonging" to someone. You had songs like "You Belong to Me" by The Duprees or even Gore’s own "That's the Way Boys Are," which basically told women to just accept that boys will be boys. You Don't Own Me flipped the script.

👉 See also: Kate Moss Family Guy: What Most People Get Wrong About That Cutaway

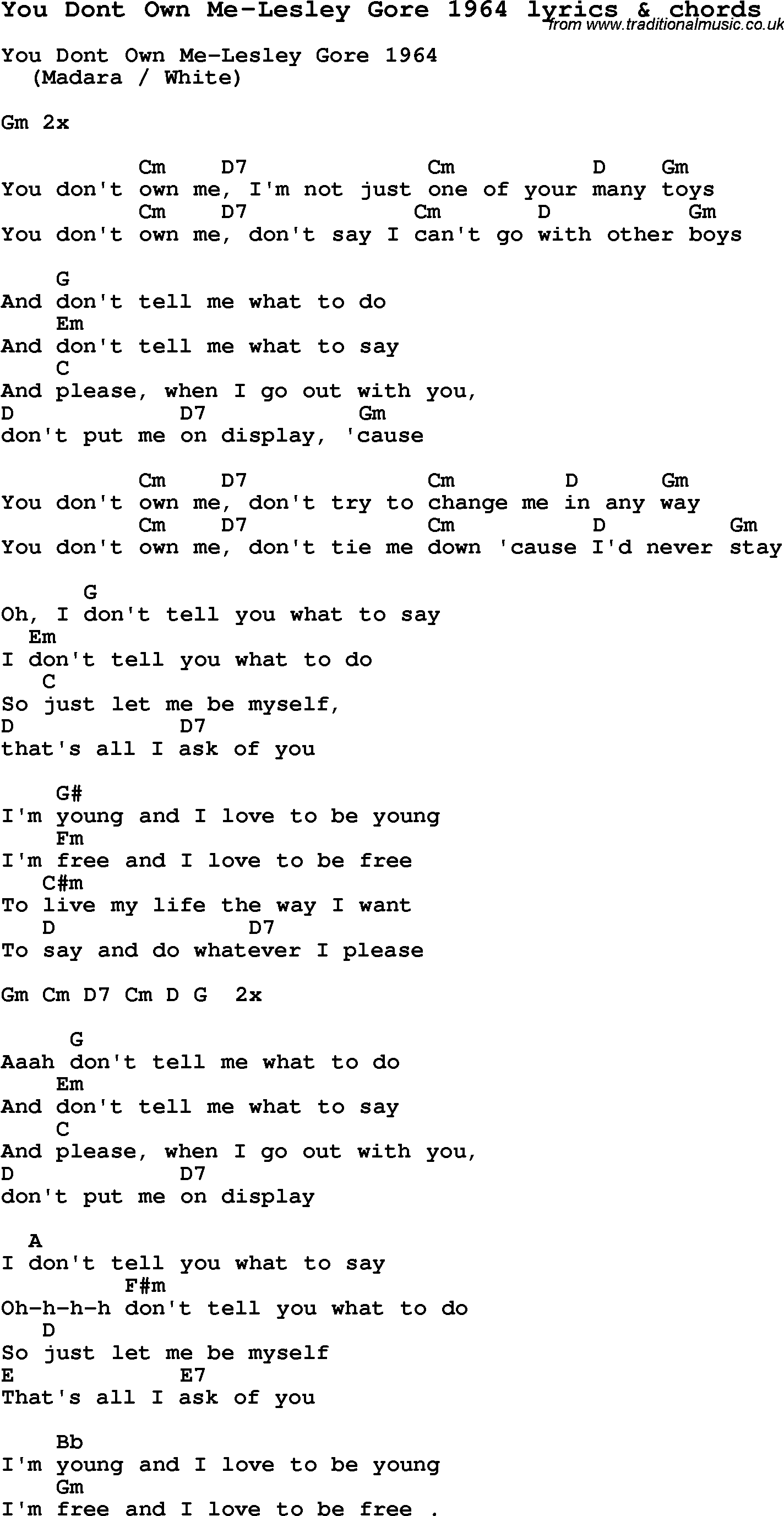

- The Tempo: It starts slow, almost like a funeral march, then builds into a triumphant, major-key chorus.

- The Modulations: The song keeps stepping up in key, which creates this feeling of rising up or growing stronger as she sings.

- The Directness: "Don't tell me what to do / Don't tell me what to say." It’s not a request. It’s a command.

Quincy Jones produced the track. Yeah, that Quincy Jones. He was only in his late 20s then, but he knew how to make a record sound massive. He layered Gore’s voice to give it a "wall of sound" quality that made her sound ten feet tall.

Stalled by the Fab Four

The song was a massive success, but it famously hit a ceiling. It spent three weeks at No. 2 on the Billboard Hot 100 in February 1964. What was stopping it from reaching the top? The Beatles.

"I Want to Hold Your Hand" was the juggernaut that blocked Lesley Gore from the No. 1 spot. It’s sort of poetic if you think about it. The "innocent" boy-girl romance of the British Invasion was keeping the early stirrings of the feminist movement at bay, at least on the charts. But while the Beatles' song is a great pop relic, Gore's track became a blueprint for decades of protest music.

A Legacy That Refuses to Quit

The song didn't die out with the 60s. It sort of became a shape-shifter. In 1996, it had a massive revival in the movie The First Wives Club. Watching Bette Midler, Goldie Hawn, and Diane Keaton sing it in all-white outfits was a core memory for an entire generation of women. It turned the song into a "divorce anthem" and a celebration of sisterhood.

✨ Don't miss: Blink-182 Mark Hoppus: What Most People Get Wrong About His 2026 Comeback

Then came the 2015 cover by Grace (featuring G-Eazy). It’s kind of cool that Quincy Jones actually returned to produce that version, too. It introduced a Gen Z audience to the lyrics just as the Me Too movement was starting to gain momentum. Gore herself used the song in a 2012 PSA to encourage women to vote and protect reproductive rights. She knew what she had. She called it her "signature song" and said she could never find anything stronger to close her shows with.

The Real Lesley Gore

People often forget that Lesley Gore was living a double life. While she was singing about "other boys" in her songs, she was actually a lesbian. She didn't come out publicly until 2005, but she lived with her partner, Lois Sasson, for over 30 years.

Knowing that makes the lyrics of You Don’t Own Me hit even harder. When she sings "I'm free and I love to be free," she wasn't just talking about a bossy boyfriend. She was talking about her right to exist in a world that wanted her to fit a very specific, heteronormative mold. She was a Jewish, lesbian feminist icon before those terms were even part of the mainstream conversation.

What Most People Get Wrong

There's a misconception that the song was "manufactured" feminism. Some critics argue that because it was written by men and produced by a man, it can't be a true feminist anthem.

🔗 Read more: Why Grand Funk’s Bad Time is Secretly the Best Pop Song of the 1970s

That feels sorta reductive.

Interpretation matters. Gore took those words and gave them a voice that didn't sound like a "toy." She looked directly into the camera lens with a defiance that was genuinely scary to people in 1963. You can't manufacture that kind of grit. It’s the difference between reading a script and believing it.

How to Listen to it Today

If you want to really get why this song still works, don't just put it on as background noise.

- Listen to the 1963 original first. Pay attention to the way the drums sound like a heartbeat speeding up.

- Watch the live footage. Look at Gore’s facial expressions. She’s not smiling like a typical 60s pop star. She looks annoyed. She looks done.

- Check out the 2005 re-recording. It’s from her album Ever Since. Her voice is deeper, more soulful, and you can hear the weight of forty years of life behind every syllable.

You Don’t Own Me isn't a museum piece. It’s a living document. Whether it's being sampled in a rap song or sung at a protest march, the core message remains the same: autonomy isn't a gift; it's a right.

If you're looking to dive deeper into the era's shift from bubblegum to protest, you might want to look into the 1963 Mercury Records sessions or the influence of Quincy Jones on early 60s pop vocalists. You could also compare Gore's trajectory with artists like Dusty Springfield, who also struggled with the "girl next door" image while harboring a much more complex internal life. The music is just the surface; the real story is always in the defiance.