You probably learned in high school chemistry that noble gases are the "loners" of the periodic table. They’re stable. They’re satisfied. They have that "perfect" octet of electrons that every other element is desperately trying to achieve through messy breakups and aggressive takeovers. So, when people ask does xenon lose or gain electrons and how many, the textbook answer used to be a flat "neither."

But textbooks are often oversimplified versions of a much weirder reality.

Honestly, xenon is the rebel of the noble gas family. While neon and helium are content to sit in their corner doing absolutely nothing, xenon is surprisingly social under the right—or rather, the most extreme—conditions. It doesn't just sit there. It reacts. It bonds. It defies the old "rule of eight." Understanding whether it gives up its electrons or hoards them requires looking at how much energy it takes to pester a "stable" atom into doing something it wasn't designed to do.

The Short Answer: Xenon Loses Electrons

If you’re looking for the quick "yes or no," here it is: Xenon loses electrons. It almost never gains them. In the world of chemistry, we talk about electronegativity—the measure of how badly an atom wants to hog electrons. Xenon has a relatively high ionization energy compared to alkali metals, but compared to its noble gas siblings like helium or neon, it's actually a bit of a pushover.

Because xenon is so large, its outermost electrons are far away from the positive pull of the nucleus. There’s a lot of "shielding" going on. Imagine trying to keep track of a toddler in a tiny room versus a crowded stadium; the stadium is the xenon atom, and those outer electrons are the toddlers wandering near the exit. Because they are so far out, a very "greedy" element—like fluorine or oxygen—can come along and rip those electrons away.

💡 You might also like: World War 1 Planes: What Most People Get Wrong About Early Aerial Combat

The Magic Number: How Many Electrons Does It Lose?

Xenon doesn't just lose one electron and call it a day. Depending on who it’s "hanging out" with, it can lose multiple. The most common oxidation states for xenon are +2, +4, +6, and even +8.

Wait. +8?

Yeah. That means in compounds like xenon tetroxide ($XeO_4$), xenon is essentially sharing or "losing" all eight of its valence electrons to the oxygen atoms. It’s a total shell-out.

In the more common xenon difluoride ($XeF_2$), it loses two. In xenon tetrafluoride ($XeF_4$), it loses four. The chemistry here is fascinating because it proves that the "noble" part of its name is more of a suggestion than a law. It takes an incredible amount of energy to make this happen, but once it does, xenon becomes a central hub for some of the most powerful oxidizing agents known to man.

Why Doesn't It Gain Electrons?

You’ll basically never see xenon gain an electron to become a negative ion ($Xe^-$). Why? Because its electron shells are already full.

Adding an extra electron would mean forcing it into a brand-new, higher-energy shell. It’s like trying to squeeze an extra passenger onto a bus where every seat is taken and the roof is made of spikes. It just isn't energetically favorable. Nature likes the path of least resistance. Losing electrons to a bully like fluorine is hard, but gaining an extra one is nearly impossible in any stable sense.

The Neil Bartlett Breakthrough

For decades, scientists thought xenon was totally inert. Then came 1962. Neil Bartlett, a chemist at the University of British Columbia, realized that a specific platinum-fluorine compound was so reactive it could pull an electron off of oxygen. He noticed that the energy required to pull an electron off oxygen was almost identical to the energy required to pull one off xenon.

He tried it. It worked.

He created the first noble gas compound, xenon hexafluoroplatinate. This shattered the idea that noble gases were chemically "dead." It proved that if you have a strong enough vacuum-cleaner of an element, you can suck the electrons right off a xenon atom.

How the Process Actually Works

When we talk about xenon losing electrons, we're talking about covalent bonding where the electrons are pulled heavily toward the other atom. In $XeF_2$, for example, the xenon atom is in the middle.

📖 Related: How to Share Private GitHub Repo Access Without Breaking Your Security

The fluorine atoms are so electronegative (electron-hungry) that they distort the xenon’s electron cloud. Even though they are "sharing," the fluorine is doing 90% of the "holding." In chemical bookkeeping, we count this as xenon "losing" those electrons to the +2 oxidation state.

Real-World Applications of Xenon's Electron Loss

This isn't just lab-coat theory. Xenon's willingness to give up electrons makes it useful in some pretty high-tech ways:

- Ion Thrusters: Deep space exploration uses xenon because it's heavy and easy to ionize. NASA’s Dawn spacecraft used xenon ion engines. By stripping an electron off the xenon atom (making it $Xe^+$), engineers can use magnets to hurl that ion out the back of the ship at incredible speeds, providing thrust.

- Imaging and Lighting: Xenon flashes in cameras and high-end car headlights rely on the movement of electrons through xenon gas.

- Chemical Synthesis: Xenon fluorides are used to etch silicon chips in the semiconductor industry. They are "clean" because once the reaction is done, the xenon just floats away as a gas, leaving no messy residue.

The Electron Configuration Problem

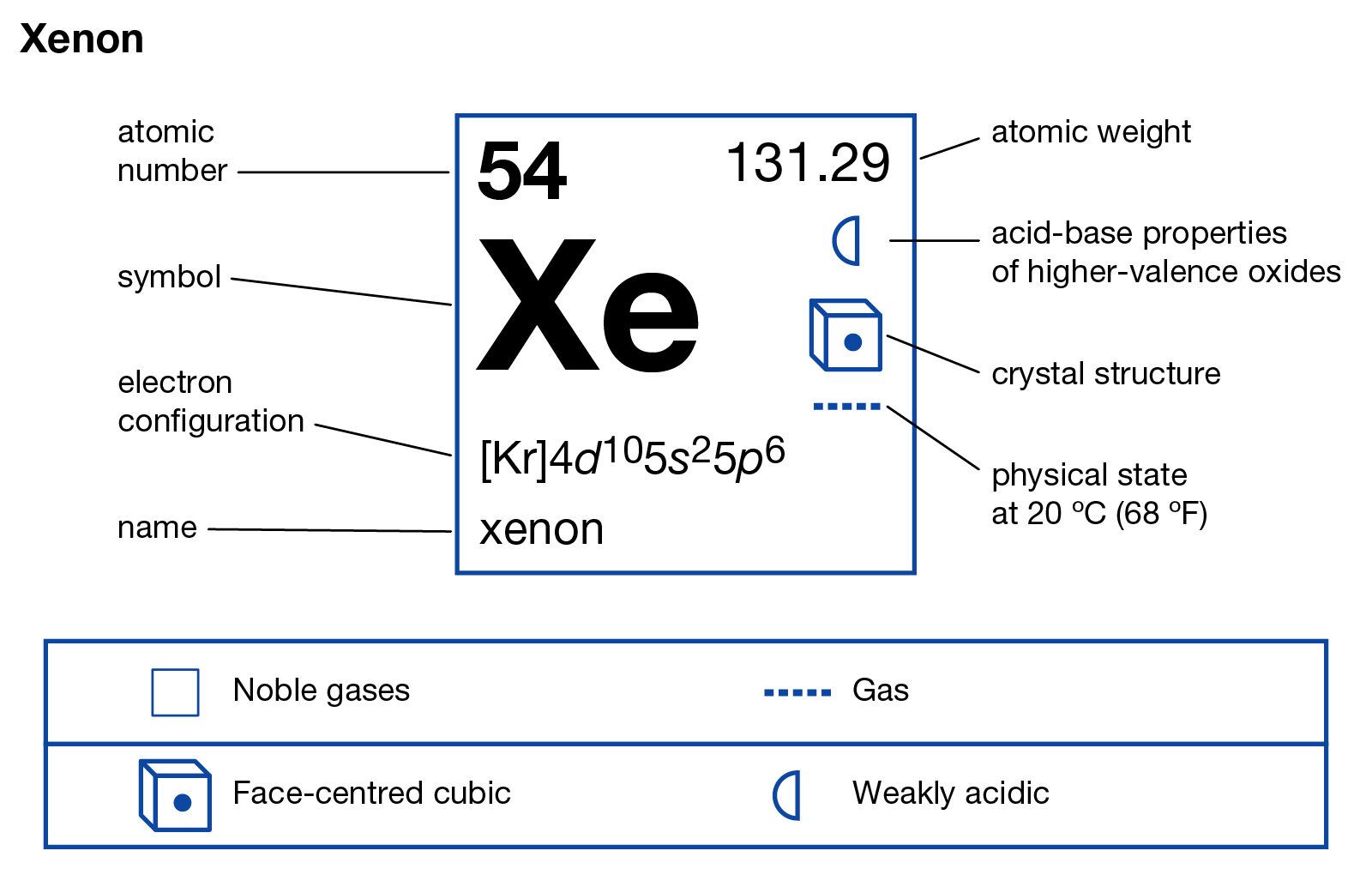

To understand the "how many" part of does xenon lose or gain electrons, you have to look at its address on the periodic table.

Xenon is element 54. Its electron configuration ends in $5s^2 5p^6$. That’s eight electrons in the outer shell.

When it reacts with fluorine, it can promote electrons from the $5p$ orbital into the empty $5d$ orbitals. This "expanded octet" is what allows it to form more than one bond. It’s essentially opening up more seats in the stadium so it can interact with more than one "guest" atom.

This is why you can get $XeF_2$, $XeF_4$, and $XeF_6$. Each step up involves "losing" more control over more electrons.

Is It Always +2, +4, +6, or +8?

Mostly. Chemistry loves even numbers when it comes to xenon because electrons usually hang out in pairs. Ripping away just one electron to create a radical is possible but usually results in something highly unstable that wants to react instantly. The even-numbered oxidation states represent a more "stable" (if you can call it that) arrangement of the remaining electron pairs.

Common Misconceptions About Xenon

Many people assume that because xenon is a "gas," it must be weak or unreactive. In reality, xenon is quite heavy—about 4.5 times denser than air. If you filled a balloon with it, it would drop to the floor like a stone.

Another mistake is thinking that all noble gases behave this way. They don't. Helium and neon have their electrons held so tightly by their nuclei that we still haven't found a way to make them form stable, neutral compounds at room temperature. Xenon is the "softie" of the group because its valence electrons are so far out in the suburbs of the atom.

Actionable Insights for Chemistry Students and Tech Enthusiasts

If you’re studying this for an exam or just trying to understand the tech behind ion drives, keep these points in your back pocket:

- Look at the partner: Xenon only loses electrons when paired with high-electronegativity elements like Fluorine, Oxygen, or Nitrogen. If those aren't present, xenon stays neutral.

- Ionization is key: In tech applications like ion thrusters, we force xenon to lose an electron using electricity, not a chemical reaction.

- The "Size" Factor: Remember that size matters. Xenon is big. Big atoms lose electrons more easily than small ones in the same group.

- Oxidation States: If you're asked "how many" electrons it loses, the most common answers are 2, 4, or 6.

Xenon is a perfect example of how "rules" in science are often just guidelines. The octet rule says xenon shouldn't react. The reality of its atomic structure says that if you push it hard enough, it’ll give up those electrons every single time. It's this specific vulnerability—this "willingness" to lose electrons—that makes it one of the most useful and interesting elements in modern propulsion and chemistry.

📖 Related: Why Pictures of Voyager 2 Spacecraft Still Look Better Than Modern CGI

To dive deeper into how this works in a lab setting, you might want to look into the work of Karl O. Christe, a leading researcher in high-energy density materials who has spent years pushing the boundaries of what noble gases can do. His work on $XeF_5^+$ and other exotic ions shows that we are still discovering new ways to make "inert" gases do our bidding.

The next time you see a xenon headlight or read about a satellite maintaining its orbit, remember: it's all happening because xenon is just "weak" enough to let go of its electrons.