It happened in the late nineties. Internet cafes in Cairo, Beirut, and Amman were packed with kids trying to talk to each other on MSN Messenger or ICQ, but they hit a massive wall. The keyboards were English. Windows didn't really "do" Arabic script back then without a fight. So, people started improvising. They didn't wait for Silicon Valley to catch up; they just grabbed the Latin keys and started mapping sounds.

That’s how Arabic alphabet with English letters—often called Arabizi, Franco-Arabic, or Moarab—became a literal lifeline for communication.

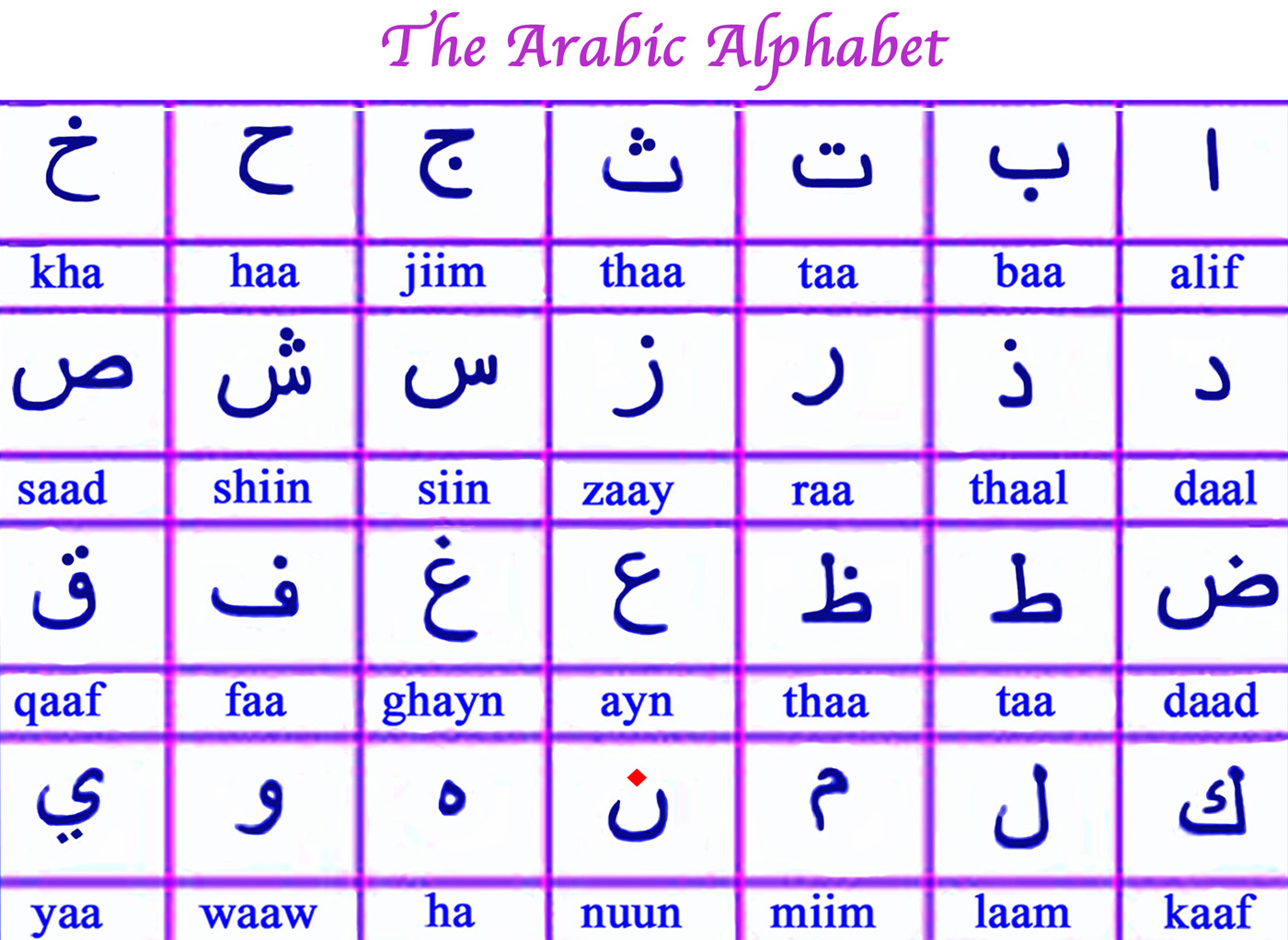

Honestly, if you look at it now, it’s a linguistic masterpiece born out of necessity. It isn't just "slang." It’s a systematic way of using numbers and Latin characters to represent phonetics that simply do not exist in the Roman alphabet. You can't just write "H" for everything because Arabic has two different "H" sounds. One is soft like "hello," and the other—the Ha (ح)—sounds like you’re breathing on a pair of glasses to clean them.

The logic behind the numbers

Why numbers? Because they look like the letters. Simple as that.

If you’ve ever seen a "3" in the middle of a word like "3arab," you’re looking at the letter Ain (ع). If you flip a 3 horizontally, it looks exactly like the Arabic character. It’s genius. This isn't some secret code; it’s visual shorthand.

Take the number 7. In Arabizi, 7 represents the letter Ha (ح). Why? Because the numeral 7 looks like the sharp angle of the Arabic letter. Then you have the 2, which represents the Hamza (ء), that little glottal stop you hear in the middle of the word "uh-oh."

Here is how the most common mappings usually shake out in daily texts:

The number 3 is for Ain (ع). Sometimes people add an apostrophe—3'—to make it a Ghayn (غ), though many just use "gh."

💡 You might also like: Finding the most affordable way to live when everything feels too expensive

The number 7 is the heavy Ha (ح).

The number 5 is the Kha (خ), that throat-clearing sound. Think of the name Khaled; in Arabizi, it's often 5aled.

The number 9 represents Sad (ص), because the loop of the 9 mimics the loop of the Arabic letter.

It’s messy. It’s inconsistent. Depending on whether you're in Morocco or Lebanon, the "8" might mean something different, or someone might use "q" instead of "9" for certain sounds. But it works. It’s a living, breathing dialect of the digital age.

Why we still use it in 2026

You’d think that since every smartphone on earth now has a native Arabic keyboard, this would have died out. It didn't.

Actually, it's faster for many. If you grew up typing on QWERTY, switching your brain to the Arabic layout feels like wading through molasses. Speed is everything. When you're arguing in a group chat about where to get shawarma, you don't want to hunt for the Qaf. You just type "wayn el akel" and move on.

There’s also a huge cultural layer here. Using the Arabic alphabet with English letters carries a specific "vibe." It’s the language of the diaspora. It’s how a college student in London talks to their cousin in Dubai. It bridges the gap between a Western education and Middle Eastern roots.

📖 Related: Executive desk with drawers: Why your home office setup is probably failing you

Researchers like Dr. David Wilmsen, who has spent years studying Arabic sociolinguistics, have noted that Arabizi allows for a "code-switching" that feels more natural than formal Arabic (MSA). Formal Arabic is for news anchors and textbooks. Arabizi is for the soul. It’s for jokes, for flirting, and for yelling at your friends.

The controversy: Is it "killing" the language?

Not everyone is a fan. Spend five minutes in a traditional academic circle in Cairo, and you’ll hear someone lamenting the "death of the script." There are legitimate concerns that younger generations are losing their ability to write correctly in formal Arabic.

UNESCO has even raised concerns about the preservation of the Arabic script in digital spaces. When you spend 90% of your day typing in Latin characters, the complex strokes of Arabic calligraphy start to feel foreign.

But languages evolve. They always have.

Arabic itself absorbed Persian, Greek, and Latin influences centuries ago. This is just the digital version of that same process. It's not a replacement; it's an extension. Many people are perfectly "biliterate"—they can write a formal essay in beautiful Arabic script and then pivot to a rapid-fire Arabizi conversation on WhatsApp without blinking.

Cracking the code: A quick reference

If you’re trying to read a message and it looks like a math equation, don't panic.

- 2 = ء (Hamza): Like "M2al" (said/proverb).

- 3 = ع (Ain): Like "3arab" (Arabs).

- 5 = خ (Kha): Like "5alas" (Finished/Enough).

- 7 = ح (Ha): Like "Habibi" (My love).

- 8 = ق (Qaf): (Used more in North Africa) or sometimes representing the G sound.

- 9 = ص (Sad): Like "9aba7" (Morning).

Notice how the vowels are usually just ignored or handled by English vowels (a, e, i, o, u). Because Arabic is a "root-based" language, you mostly just need the consonants to understand the meaning. Your brain fills in the gaps. It's basically a puzzle that everyone in the region already knows how to solve.

👉 See also: Monroe Central High School Ohio: What Local Families Actually Need to Know

Beyond the numbers: Regional flavors

The way someone writes the Arabic alphabet with English letters tells you exactly where they are from.

A Lebanese person might use more French-influenced spelling. They might write "Bonjour" and then finish the sentence in Arabizi. A Maghrebi user from Morocco or Algeria will mix in French words and use "9" or "k" differently because their spoken dialect is so distinct.

In the Gulf, you’ll see a heavier use of the "6" for the letter Taw (ط). It’s a nuance that shows how deeply integrated this system has become. It isn't a monolith. It has its own accents, its own slang, and its own rules of etiquette. For example, using too many numbers can sometimes feel "old school" or like you're trying too hard, while using too few can make the words hard to read.

Is it here to stay?

Most likely, yes.

Even with AI-driven voice-to-text and better Arabic keyboards, the Latin-script version of Arabic has become a brand. It’s used in advertising, in song titles on Spotify, and in movie credits. It has moved from a technical workaround to a stylistic choice.

It represents a generation that is comfortable in two worlds at once. It’s the sound of the modern Arab world—fast, adaptive, and slightly chaotic.

If you want to master this, start by looking at the shapes. Stop seeing "7" as a number and start seeing it as a letter. Once you make that mental flip, the whole language opens up.

Next steps for mastering Arabizi:

- Download a "Franco" dictionary app. There are several community-driven tools that can translate specific Arabizi words back into Arabic script if you get stuck on a specific number.

- Focus on the "Big Three". Learn 3, 7, and 5 first. These make up about 80% of the number usage in most casual conversations.

- Listen as you read. Try to say the words out loud. Usually, the phonetic English spelling is very literal. If it looks like "7abibi," say it out loud, and the "7" sound will naturally slot into place as you recognize the word.

- Observe the vowels. Remember that "e" and "i" are often used interchangeably depending on the local dialect's pronunciation of the Kasra.

- Practice on social media. Follow creators from the Levant or Egypt and read their comments sections. It’s the best "textbook" you’ll ever find for real-world usage.