You're sitting at your desk, staring at a blinking cursor, trying to figure out how to sum up three years of someone’s unpaid labor without sounding like a corporate robot. It's tough. Most people think a reference letter for volunteer worker needs to be this stiff, formal document filled with "to whom it may concern" and "diligent worker" clichés. Honestly? That’s the quickest way to get the letter ignored. Hiring managers and admissions officers at places like the Peace Corps or big nonprofits like the Red Cross see hundreds of these. They want to see the person, not just the paperwork.

When someone asks you for a reference, they aren’t just asking for a list of chores they did. They’re asking you to put your own reputation on the line to vouch for their character. It’s a big deal. Whether they’re trying to land a paid job in the non-profit sector or applying for a competitive grad school program, your words carry weight. You have to bridge the gap between "they showed up on time" and "this person is a vital asset to any team."

🔗 Read more: How to Actually Get That Chase Bank Joining Bonus Without the Usual Headaches

Why Generic Letters Fail (And How to Fix Yours)

Most people write these letters by downloading a template and swapping out the names. Don't do that. It feels hollow. A truly effective reference letter for volunteer worker focuses on the "why" behind the service. Did they volunteer because they had to meet a court requirement, or did they spend their Saturdays at the food bank because they actually care about food insecurity?

Specificity is your best friend here. Instead of saying "Sarah was a great helper," say "Sarah managed our intake system during the holiday rush, handling 40 families an hour without losing her cool." See the difference? One is a vague compliment; the other is proof of performance.

The Structure That Works

Forget the 1-2-3-4 numbering systems you see in textbooks. You want a flow that feels like a conversation between two professionals. Start with the context. How do you know them? If you were their supervisor at a local animal shelter, say that immediately. "I’ve spent the last 18 months watching Marcus handle some of the most difficult cases at our shelter" is a killer opening line. It establishes your authority and his experience in one go.

Next, dive into the soft skills. In the volunteer world, soft skills are actually "hard" skills. Reliability, empathy, and initiative are the currency of non-profits. If you're writing for someone who helped at a hospital, talk about their bedside manner. If they were a volunteer bookkeeper, talk about their integrity and attention to detail.

Proving Value Without a Paystub

One of the biggest hurdles in writing a reference letter for volunteer worker is the lack of traditional metrics. In a corporate job, you can say "John increased sales by 20%." In a volunteer role, you might be measuring "smiles" or "bags of trash collected." You have to get creative with how you define success.

Think about the "mission-critical" moments. Was there a time the power went out and the volunteer stepped up? Did they suggest a new way to organize the donation bin that saved everyone three hours a week? That’s the gold. These anecdotes prove that the person wasn't just a warm body in a chair—they were thinking, contributing, and improving the organization.

Addressing the Elephant in the Room: The "Volunteer" Label

There is a weird, lingering stigma that volunteer work isn't "real" work. We know that’s nonsense. According to AmeriCorps, volunteers are often more likely to find employment than non-volunteers because they’ve built a diverse network. Your letter needs to treat their role with the same gravity as a C-suite position. Use professional terminology. If they were a "camp counselor," they were "leading youth development programs." If they "helped with the website," they "contributed to digital communications and brand management."

The Legal and Ethical Bit

Wait, can you get sued for a reference letter? It's rare, but you should stick to the facts. Stick to what you observed. If you say someone is "the most honest person on Earth" and they later get caught embezzling, that’s a headache you don't want. Stick to: "During her tenure, she handled all cash donations with total transparency and followed all our internal protocols." It’s professional, it’s factual, and it protects everyone involved.

Also, be honest with the volunteer. If you can’t write a glowing letter, it’s better to decline. A lukewarm letter is often worse than no letter at all. Just say, "I don't feel I've worked with you closely enough to provide the detailed reference you deserve." It's polite and saves them from a mediocre recommendation.

The Anatomy of a High-Impact Paragraph

Check out this illustrative example of a middle paragraph that actually says something:

"What struck me most about David wasn't just his willingness to show up at 6:00 AM for the Saturday soup kitchen shifts, but how he interacted with our guests. He didn't just hand out bowls; he learned names. He noticed when one of our regulars, a veteran named Mr. Henderson, hadn't shown up for two days and flagged it for our social services team. That kind of situational awareness and genuine empathy is something you can't teach in a training manual."

This works because it shows David’s character through action. It proves he’s observant and proactive. Any employer would want that guy on their team.

Getting the Formatting Right

You don’t need a fancy letterhead, but it helps. If your organization doesn't have one, just put your contact info at the top. Use a standard font like Arial or Times New Roman. Keep it to one page. No one—and I mean no one—is reading a three-page letter of recommendation for a volunteer role.

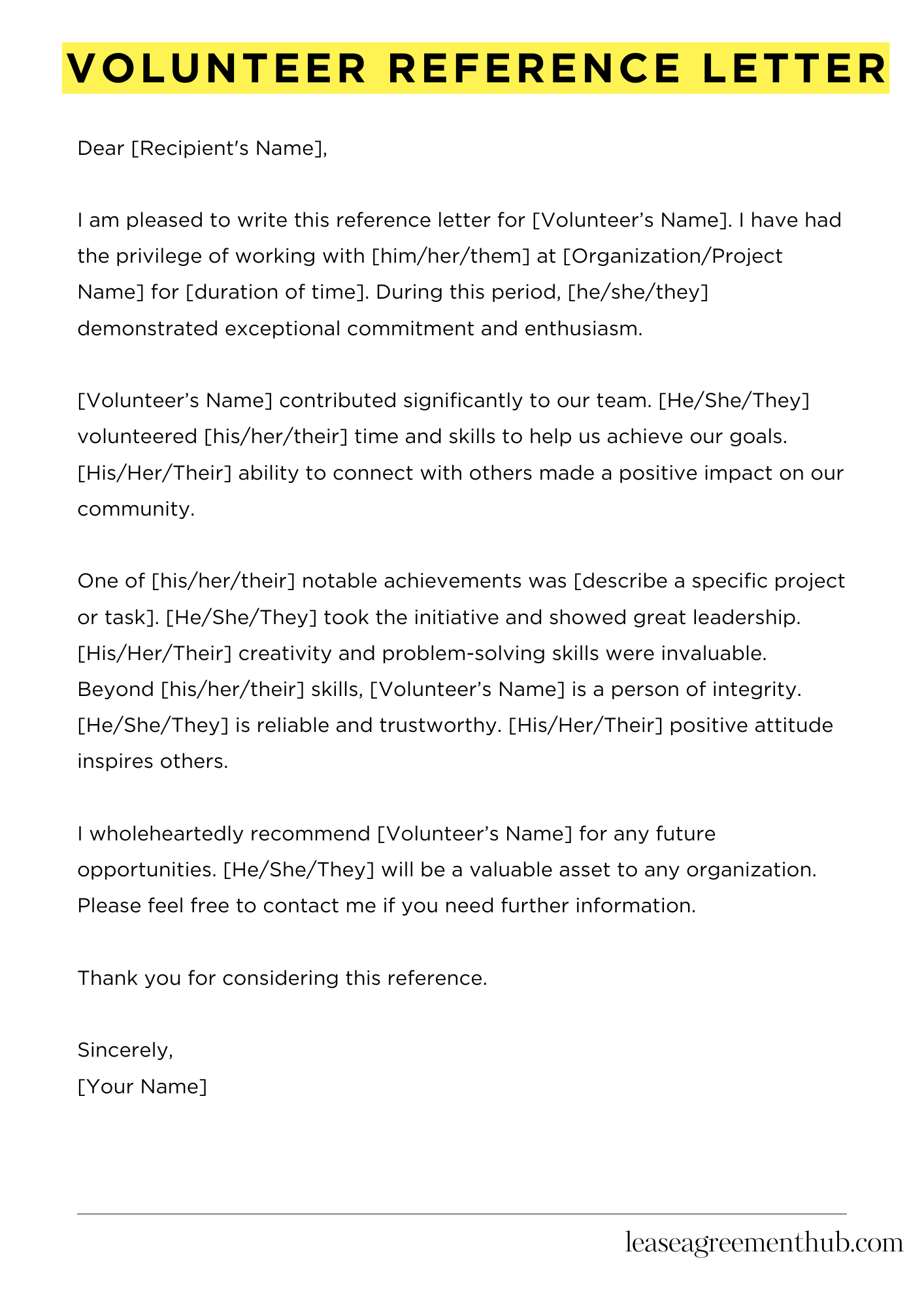

- Header: Your name, title, organization, and date.

- Salutation: "Dear [Name of Hiring Manager]" or "To the Selection Committee."

- The Hook: Who you are and who you're talking about.

- The Evidence: Two paragraphs of specific stories and skills.

- The Vouch: A final, strong statement of recommendation.

- The Sign-off: "Sincerely" or "Best Regards."

Key Takeaways for Your Draft

Basically, you’re telling a story. You're the narrator, and the volunteer is the hero. Your job is to make the reader believe in that hero.

Don't overthink the vocabulary. You don't need to use words like "utilize" when "use" works just fine. Keep it punchy. Keep it real. If they were a bit of a jokester who kept morale high during stressful shifts, mention it! Culture fit is a huge part of hiring, and showing that someone is a joy to work with is a massive selling point.

Putting It All Together

When you're finalizing the reference letter for volunteer worker, read it out loud. If it sounds like something a robot generated, go back and add a specific detail. Think of one time they made your life easier. Put that in there. That one detail is what the recruiter will remember after they’ve closed the file.

- Verify the dates. Make sure you have their start and end dates right. Accuracy matters.

- Ask for the job description. If they are applying for a specific job, ask to see the posting. You can then tailor your letter to highlight the skills that employer is looking for.

- Use "Power Verbs." Instead of "helped," use "facilitated," "coordinated," or "spearheaded."

- Proofread. Typos in a reference letter make both you and the volunteer look bad.

Now, take that draft and send it. You're doing a good thing. Helping someone transition from volunteer work to a career is one of the most impactful things a supervisor can do.

Next Steps for Your Reference Letter

- Draft the "Evidence" section first: Write down three specific moments where this volunteer impressed you before you even touch the formal intro.

- Check the submission requirements: Some organizations require the letter to be sent directly from your email or uploaded to a specific portal—don't just give it to the volunteer and assume your job is done.

- Keep a copy for yourself: You might need to write another one for them in two years, and having the original as a starting point will save you a ton of time later.