Ever stared at a check—or a wedding invitation—and suddenly forgotten if "forty" has a "u" in it? It’s okay. Most of us do. Writing a list of numbers as words seems like it should be the easiest thing in the world, yet here we are, second-guessing ourselves every time we have to type out a formal document or a fancy letter. It's weird. We use numbers constantly, but the moment you have to convert those digits into actual letters, your brain kinda glitches out.

Numbers are the backbone of how we organize life, but the English language decided to make spelling them out a total minefield of hyphens and "and" placements.

✨ Don't miss: Fried Ribs: Why Most People Get the Crunch Wrong

Let's get the big one out of the way: it’s forty, not "fourty." I know, it makes no sense. "Four" has a "u." "Fourteen" has a "u." But forty? Forty decided to be different. It’s one of those linguistic quirks that catches people off guard when they’re writing a list of numbers as words for a professional report or a legal contract. If you get that wrong, the rest of your numbers—no matter how accurate—just look a bit off.

When to actually use a list of numbers as words

So, when do you actually stop using digits? Most style guides—like AP or Chicago—have their own opinions, and they don't always agree. Honestly, it’s mostly about consistency.

If you're following the AP Stylebook, you generally spell out numbers zero through nine. After that, you switch to digits. 10. 11. 1,000. But if you're writing a novel or a formal invitation, you might follow the Chicago Manual of Style, which tells you to spell out everything up to one hundred. That’s a huge difference. Imagine writing "ninety-nine" every single time instead of "99." It changes the whole "vibe" of the page. It looks denser. More serious.

Wait, there's a huge exception. Never start a sentence with a digit. Never. It looks messy. "10 people went to the store" is a cardinal sin in the world of editing. You have to write "Ten people went to the store." Even if the number is "One thousand four hundred and twenty-two," you spell it out if it’s at the start of that sentence. Or, you know, just rewrite the sentence so the number isn't first. That’s the pro move.

The hyphen madness

Hyphens are where people usually lose their minds. There’s a very specific rule for compound numbers: you only use a hyphen for numbers between twenty-one and ninety-nine.

- Twenty-five.

- Sixty-eight.

- Eighty-one.

But you don't use them for things like "one hundred." It’s just "one hundred." If you’re writing "one hundred twenty-five," only the "twenty-five" gets the dash. It’s a small detail, but if you’re trying to look like an expert, these are the things that matter. People notice. Or rather, they don't notice when it’s right, but they definitely feel like something is "wrong" when it’s missing.

Large numbers and the "and" controversy

Here is a hill many grammarians are willing to die on: the word "and."

In American English, you aren't supposed to use "and" when writing out whole numbers. For example, 150 should be "one hundred fifty," not "one hundred and fifty." Why? Because in mathematics, "and" usually signifies a decimal point. If you say "one hundred and fifty," some strict math teachers might argue you’re saying 100.50.

Now, in British English, they use "and" all the time. "One hundred and fifty" is perfectly standard over there. So, depending on who you're writing for, that little word can be a regional giveaway. If you’re in the US and writing a check, "one hundred fifty and 00/100" is the "correct" way, though nobody is going to bounce your check if you throw an extra "and" in there.

Counting into the millions

When you get into the big stuff, a list of numbers as words becomes a visual marathon. Let's look at a number like 1,250,500.

One million, two hundred fifty thousand, five hundred.

It’s long. It’s clunky. This is why most journalists skip the words and use a mix: "1.25 million." It’s readable. It saves space. But if you’re writing a high-end certificate or a deed, you’ve gotta go full-out with the words.

💡 You might also like: 55 pounds to kilograms: How to Get it Right Without the Guesswork

A quick reference for the tricky ones

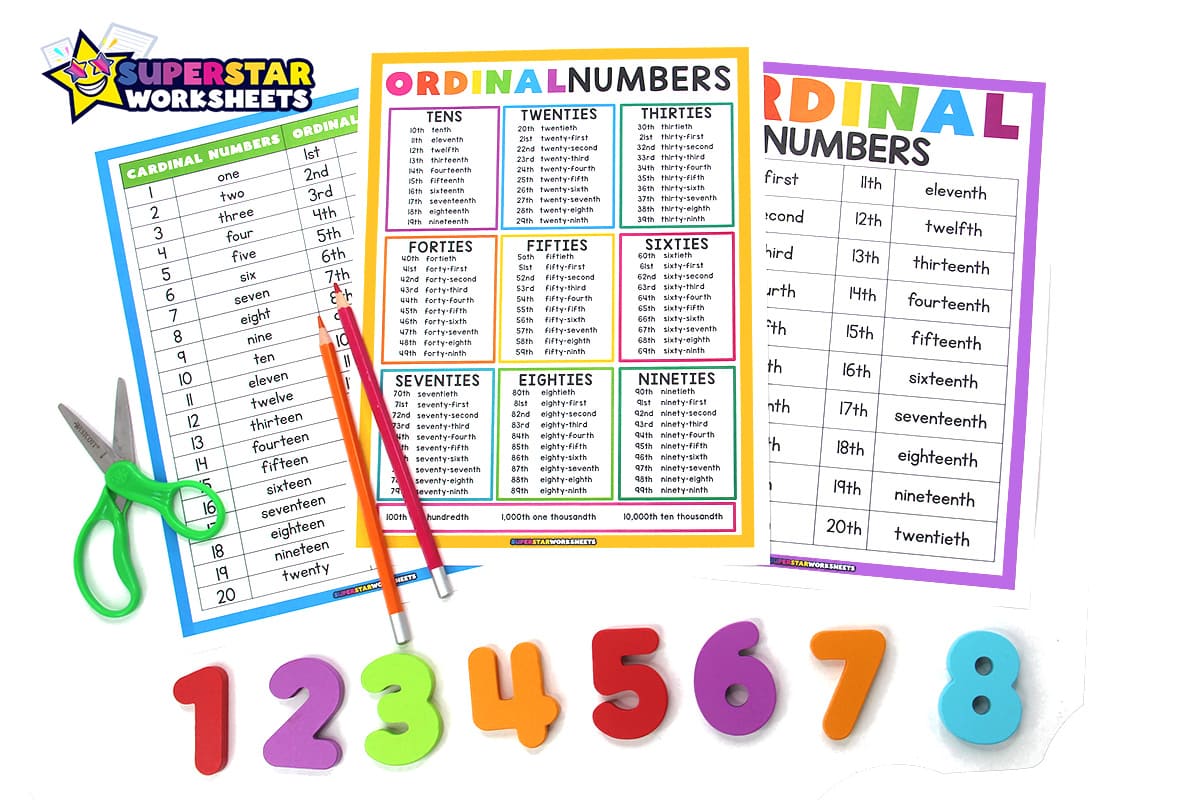

Sometimes you just need to see them. Spelling is a visual thing for a lot of us.

- Eighth: People always forget the second "h."

- Ninety: Keep the "e." Unlike "forty," ninety keeps its root word intact.

- Fourteenth: Also keeps the "u." (English is a nightmare, isn't it?)

- Twelfth: That "f" is weirdly difficult to remember to type.

Fractions and decimals

Fractions are another hyphen zone. If you're using a fraction as an adjective—like "a two-thirds majority"—you hyphenate it. If you're using it as a noun—"He ate two thirds of the cake"—you technically don't have to, though many people do just to be safe.

Decimals are almost never written as words unless you're in a very specific scientific or legal context. You wouldn’t write "thirty-five point seven." You’d just write 35.7. It’s cleaner.

Why does this even matter anymore?

You might think, "Why do I care? My phone autocorrects everything."

Well, AI and spellcheck are actually notoriously bad at the nuances of number-to-word conversion in context. They might catch a misspelling of "thirteen," but they won't tell you if you're breaking the "Chicago Manual of Style" halfway through your document. Consistency is what builds trust with a reader. If you use "9" in one paragraph and "nine" in the next, it looks like you didn't proofread. It looks sloppy.

In 2026, where everything is digital and fast, taking the time to correctly format a list of numbers as words shows a level of attention to detail that sets your work apart. It’s about the "texture" of your writing. Words feel warmer. Digits feel clinical.

Practical steps for your next project

If you're sitting down to write something that involves a lot of numbers, don't just wing it.

First, pick a style. Are you going AP (0-9 are words) or Chicago (0-100 are words)? Stick to it like glue.

Second, do a "Ctrl+F" for "40" and "90" at the end. Those are the most common typos. Check your hyphens. If it's a compound number between 21 and 99, it needs that little dash.

Third, look at your sentence starters. If a sentence begins with a number, spell it out or move it.

Finally, read it out loud. If you’re writing out "one thousand eight hundred seventy-six," and you find yourself stumbling over the words, maybe that’s a sign to use the digits instead. Unless it’s a formal invitation—then you just have to suffer through the long version.

Writing numbers as words isn't just a grammar rule; it's an aesthetic choice that changes how people perceive your message. Keep it consistent, watch your "u"s and "f"s, and remember that when in doubt, "forty" is always the one trying to trick you.