It hits you at the weirdest times. Maybe you’re standing in the grocery aisle looking at the specific brand of hot sauce he used to put on everything, or you hear a classic rock song through a cracked car window. Suddenly, you're mentally drafting a message to my dad in heaven. It’s a strange, heavy, yet oddly comforting impulse. We know they can't text back. We know the "Seen" receipt isn't coming. Yet, the urge to communicate remains one of the most persistent parts of the human grieving process.

Grief isn't a straight line. It’s more like a messy scribble. Some days you’re fine; other days, the silence is deafening. Writing or speaking to a parent who has passed away isn't about being "stuck" in the past. Honestly, it’s about integration. Dr. Robert Neimeyer, a leading expert on grief and director of the Portland Institute for Loss and Transition, often discusses "meaning-making." He suggests that we don't actually "get over" loss. Instead, we learn to carry it. We build a new relationship with the person that doesn't depend on their physical presence.

The Psychology Behind the Connection

Why do we do it? Is it just wishful thinking? Not really. Psychologists call this "Continuing Bonds" theory. Back in the day, the old-school medical advice was all about "closure." You were supposed to say goodbye, detach, and move on. That’s kinda harsh, isn't it?

Modern research, particularly the work of Klass, Silverman, and Nickman, flipped that script in the late 90s. They argued that maintaining a connection with the deceased is actually healthy and normal. When you write a letter to my dad in heaven, you aren't denying reality. You’re acknowledging that while his body is gone, his influence on your identity is permanent. You're keeping the dialogue open because he's still a part of who you are.

It’s about the "internalized" father. You probably already know what he’d say about your new job or that weird noise your car is making. Writing it down just makes that internal conversation tangible. It’s a way to process the "undelivered" thoughts that pile up in your brain like junk mail.

🔗 Read more: Marie Kondo The Life Changing Magic of Tidying Up: What Most People Get Wrong

Different Ways People Send Their Messages

There’s no "right" way to do this. Some people find the idea of a formal letter too daunting. They feel like they have to write something profound or poetic. You don't.

- The Unsent Text: Many people keep their dad’s phone number in their contacts for years. They send little updates. "The Mets won today." "I finally fixed the sink." It’s quick. It’s dirty. It works.

- The Journal Entry: This is for the long-form stuff. The stuff that hurts. The stuff you can't say out loud because it feels too heavy for a Tuesday afternoon.

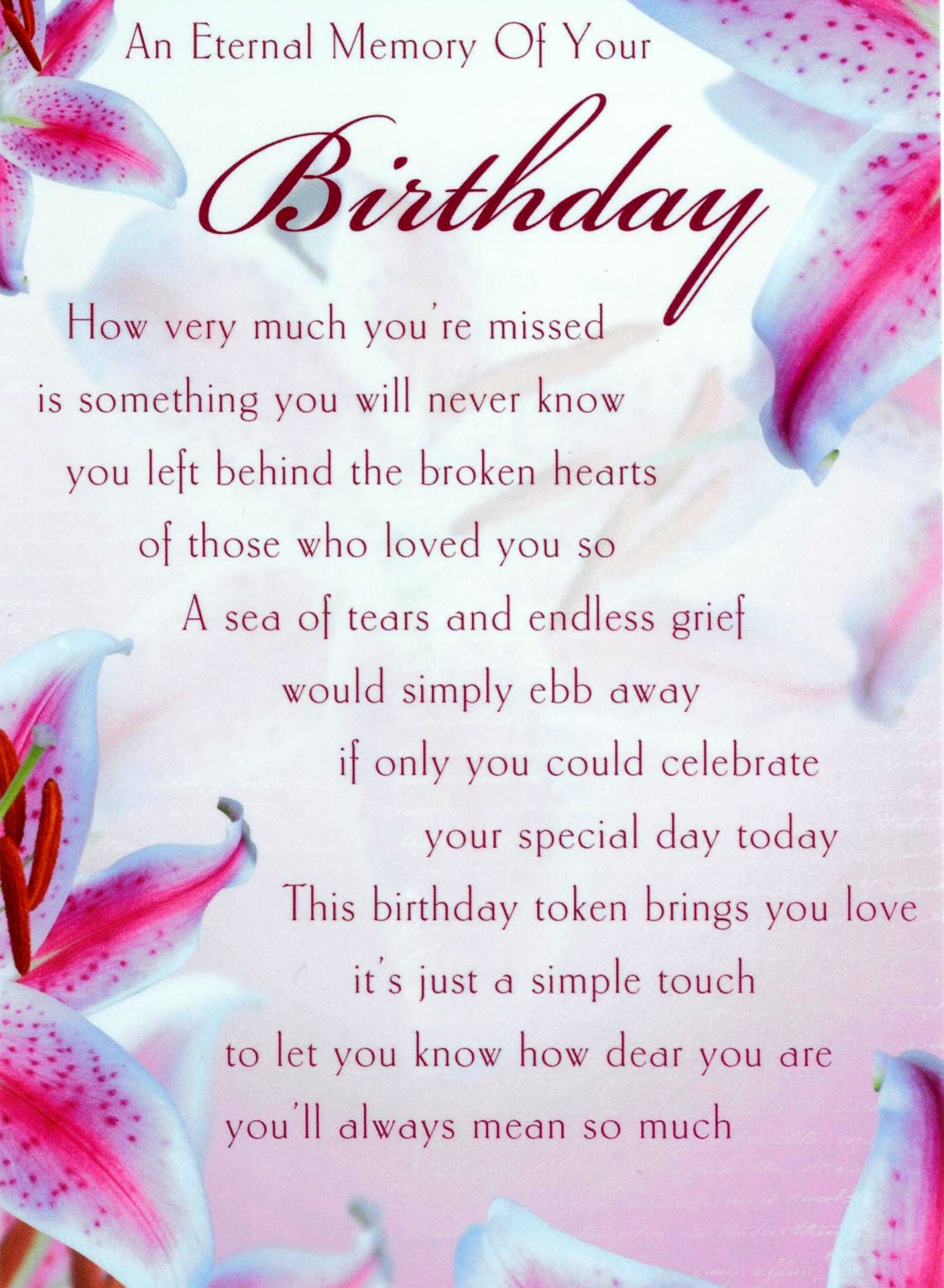

- The Public Tribute: Social media has changed everything. Posting a photo on his birthday or Father’s Day is a way of saying, "He existed, and he mattered." It’s a communal form of writing to my dad in heaven that lets others share in the memory.

- The Physical Object: Some folks write notes and tuck them into a suit pocket he used to wear or leave them at a gravesite. There’s something powerful about the physical act of leaving a message in a place that feels "his."

When the Silence Gets Too Loud

Let's be real for a second. Sometimes, writing to him makes the absence feel worse. You write the words, you look at the page, and the realization hits again: he’s not here. That’s the "sting" of grief that never quite disappears.

Therapists often use "Empty Chair" work, a technique from Gestalt therapy. You sit across from an empty chair and imagine him there. You talk. You vent. You cry. It sounds "extra," but it’s a massive release. It’s especially helpful if there were things left unsaid. Maybe you didn't get to apologize for that fight you had in 2014. Maybe you never told him how much you appreciated the way he taught you to drive. Writing a letter to my dad in heaven allows for a "corrective experience." You get to say the things that the suddenness of death stole from you.

What Most People Get Wrong About "Moving On"

People will tell you to "find closure." That's a myth. Closure is for bank accounts and real estate deals. It’s not for parents. You don't close the book on your father. You just start a new volume where he’s a character in the prologue instead of a protagonist in the current chapter.

💡 You might also like: Why Transparent Plus Size Models Are Changing How We Actually Shop

The goal isn't to stop thinking about him. The goal is to think about him without it shattering your entire day. Continuing the conversation—whether through a prayer, a letter, or just a quiet thought while you’re mowing the lawn—is part of that stabilization. It turns an acute, piercing pain into a dull, manageable ache.

Real Examples of Living Legacies

I once spoke with a woman who wrote a letter to her father every time she hit a major milestone. She had a box full of them. She wasn't "crazy." She was a high-functioning executive who just needed a place to put her pride and her sorrow. Another man told me he buys a specific cigar on his dad's birthday, sits on the porch, and "talks" through the year's highlights.

These aren't just rituals; they are anchors. In a world that moves incredibly fast, these moments of writing to my dad in heaven force us to slow down and remember our roots.

Actionable Steps for Processing Your Loss

If you’re feeling the weight of things left unsaid, or if you just miss him more than usual today, here is how you can practically handle that impulse.

📖 Related: Weather Forecast Calumet MI: What Most People Get Wrong About Keweenaw Winters

1. Don't overthink the format. If you want to write a letter, do it. If you want to talk to the air while you’re driving alone, do that. The "medium" doesn't matter as much as the "message." Don't worry about grammar or whether you sound "weird." You’re writing for an audience of one.

2. Focus on specifics. Instead of just saying "I miss you," try "I missed you when I saw that old Chevy today." Specificity grounds the emotion. It makes the memory sharper and more rewarding to revisit.

3. Address the "Unfinished Business." If you have guilt, put it on paper. "I’m sorry I didn't visit more that last month." Research shows that externalizing these feelings reduces their power over your subconscious. You aren't necessarily "sending" the apology, but you are releasing it from your own chest.

4. Create a "Connection Ritual." Pick a date—his birthday, the anniversary of his passing, or even just a random Sunday—to consciously "check in." This gives your grief a designated time and place so it doesn't leak into your work week quite as much.

5. Consider a Legacy Project. If writing letters isn't enough, do something he would have loved. Donate to a charity he supported. Finish that woodworking project he started. Writing to my dad in heaven can be done with your hands just as easily as with a pen.

Grief is a long-term transition from "presence" to "memory." Talking to him, in whatever way feels natural to you, is just your heart's way of navigating that transition. It’s okay to keep the conversation going. In fact, it’s probably one of the most human things you’ll ever do.