It happened fast. One day you’re a shopkeeper in Seattle or a farmer in the Salinas Valley, and the next, there’s a poster on a telephone pole telling you to pack what you can carry. That’s the reality of World War Two internment camps. Honestly, it's a part of history that feels increasingly surreal as time passes, yet its shadow looms over every conversation we have today about civil liberties and "national security."

Most people think they know the gist. Pearl Harbor happens, fear spikes, and the government moves people away from the coast. But the granular reality? It was messier. It was a logistical nightmare built on a foundation of shaky intelligence and systemic bias. We aren't just talking about a few "relocation centers." We are talking about a massive, federally mandated upheaval that upended the lives of over 120,000 people, the majority of whom were American citizens.

The Paper Trail of Executive Order 9066

President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066 on February 19, 1942. This wasn't a law passed by Congress after a long debate. It was an executive action. It gave the military the power to designate "military areas" from which "any or all persons may be excluded."

Notice the language. It didn't specifically say "Japanese Americans." It didn't have to.

Lieutenant General John L. DeWitt, who headed the Western Defense Command, was pretty blunt about his motivations. He famously remarked that "a Jap's a Jap," regardless of citizenship. This sentiment drove the creation of the Wartime Civil Control Administration (WCCA) and, later, the War Relocation Authority (WRA).

People had days to sell their homes. Literally days. Imagine trying to liquidate a lifetime of assets—tractors, furniture, family businesses—in 72 hours. Predators moved in. People bought up Japanese-owned land for pennies on the dollar. It was a state-sanctioned fire sale.

The Assembly Centers vs. The Permanent Camps

Before the famous sites like Manzanar or Rohwer were even finished, people were shoved into "Assembly Centers." These were makeshift. They used race tracks like Santa Anita or fairgrounds like Puyallup.

Families slept in horse stalls. They still smelled like manure. You’ve got children, the elderly, and war veterans from the previous World War living on dirt floors covered in thin layers of linoleum. It was humiliating. It was also temporary, which in government-speak meant several months of squalor while the "real" World War Two internment camps were built in the interior of the country.

Life Inside the Barbed Wire

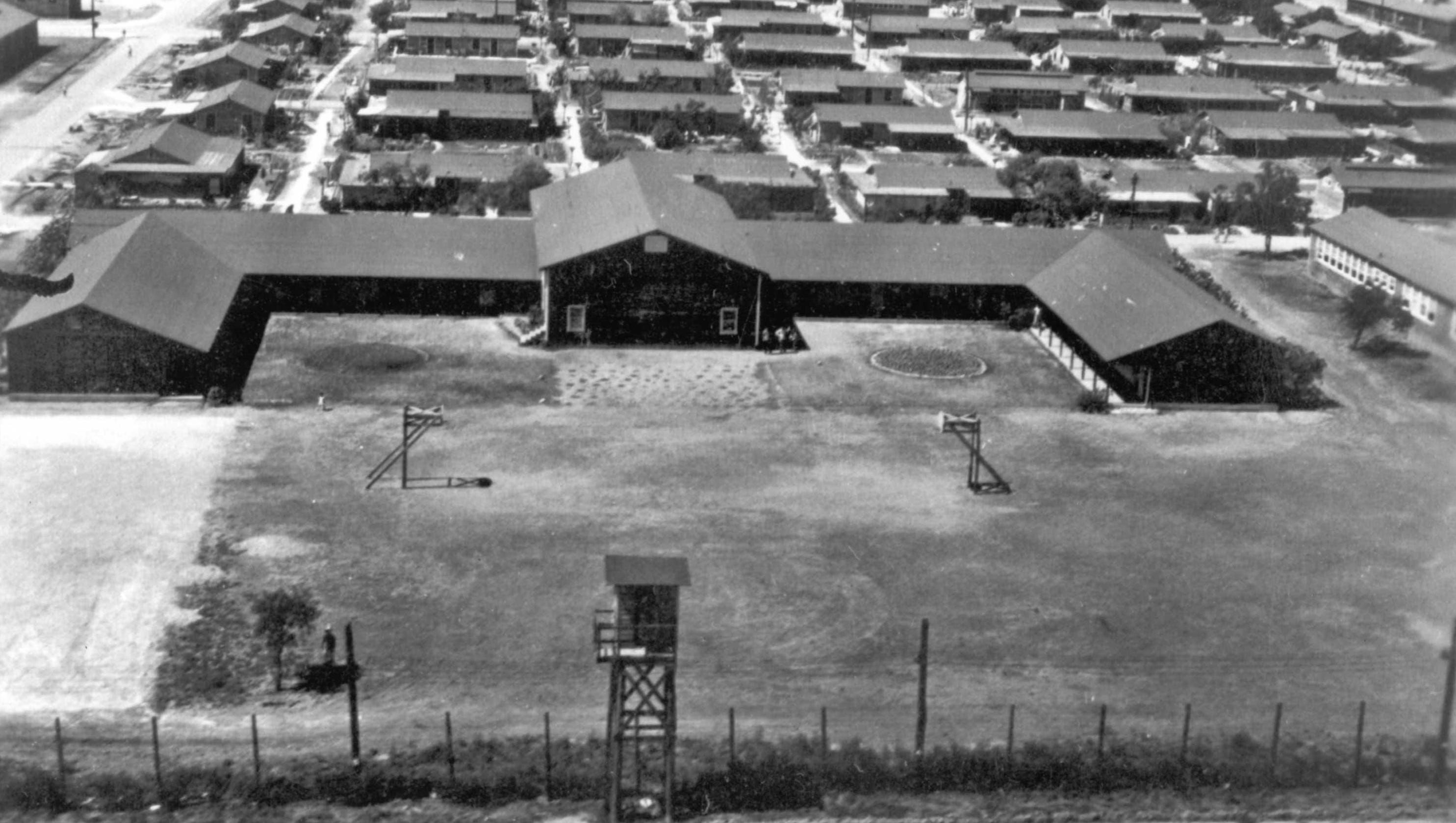

The ten primary WRA camps were located in some of the most desolate spots in America. Think scorched deserts or mosquito-infested swamps. Places like Poston in Arizona or Topaz in Utah.

The architecture was repetitive. Black tar-paper barracks. No insulation. In the summer, the heat was suffocating. In the winter, the wind whipped through the cracks in the floorboards.

Privacy? Forget it.

- Communal latrines with no partitions.

- Shared mess halls where you ate what was served, often "army slop" like canned meats and potatoes.

- Barracks rooms shared by entire families, sometimes separated only by a hanging sheet.

It broke the family unit. Usually, the father was the head of the household. In the camps, kids started eating with their friends in the mess halls instead of with their parents. The traditional authority of the elders (the Issei, or first-generation immigrants) began to crumble under the pressure of the WRA's rules, which favored the Nisei (second-generation, American-born citizens).

The Loyalty Questionnaire Mess

In 1943, the government decided to test the loyalty of the people it had already imprisoned. They issued a "Statement of United States Citizen of Japanese Ancestry."

Two questions caused total chaos.

Question 27 asked if individuals were willing to serve in the U.S. armed forces. Question 28 asked if they would swear unqualified allegiance to the U.S. and forswear any allegiance to the Japanese Emperor.

Think about the trap. If an Issei—who was legally barred from becoming a U.S. citizen—answered "yes" to Question 28, they effectively became a person without a country. They would be renouncing their only citizenship while having no path to American citizenship. If you said "no-no," you were labeled a "disloyal" and sent to Tule Lake, which became a high-security segregation center.

It was a bureaucratic disaster. It tore families apart. Some sons wanted to fight for the U.S. to prove their loyalty (forming the famous 442nd Regimental Combat Team), while their parents, understandably bitter, felt that answering "yes" was a betrayal of their dignity.

The Forgotten Camps: Germans and Italians

While the mass incarceration focused on Japanese Americans, the story of World War Two internment camps actually includes thousands of German and Italian "enemy aliens."

This part of the history is often glossed over.

Under the Alien Enemies Act of 1798, the government arrested thousands of German and Italian nationals. Many were residents who had lived in the U.S. for decades. Some were even Jewish refugees fleeing the Nazis who were ironically classified as "enemy aliens" because of their passports.

👉 See also: Aline Tamara Moreira de Amorim: What Really Happened at Devil’s Throat

The Department of Justice ran these camps, like the one in Crystal City, Texas. Crystal City was unique because it was a "family internment camp." They actually let families stay together, including Japanese, German, and Italian internees. It was a weird, multicultural microcosm of the war's contradictions, right in the middle of the Texas scrubland.

The Legal Battles That Changed Everything

It took a while for the courts to catch up. Three major cases went to the Supreme Court: Yasui v. United States, Hirabayashi v. United States, and the most famous, Korematsu v. United States.

Fred Korematsu didn't want to go. He had plastic surgery on his eyes to try and look "less Japanese" and stayed in California with his girlfriend. He was caught.

In 1944, the Supreme Court ruled against him. They said the exclusion was a "military necessity." It remains one of the most controversial decisions in American legal history. Justice Robert Jackson wrote a blistering dissent, calling the ruling a "loaded weapon" that would lie around for any future authority to use.

It wasn't until Ex parte Endo—decided the same day as Korematsu—that the court finally ruled that the government could not detain "concededly loyal" citizens. This effectively forced the WRA to start closing the camps.

The Long Road to Redress

After the war, people went home to nothing. Their businesses were gone. Their houses were sold. Many families didn't talk about the camps for forty years. The shame was too deep.

It wasn't until the 1980s that the Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians (CWRIC) concluded that the incarceration was not a result of "military necessity" but of "race prejudice, war hysteria, and a failure of political leadership."

In 1988, President Ronald Reagan signed the Civil Liberties Act. It provided a formal apology and $20,000 in restitution to each surviving internee. It wasn't about the money. It was about the acknowledgement.

Why We Still Talk About This

History isn't just a list of dates. World War Two internment camps serve as a warning. They show how quickly the rule of law can bend under the weight of fear.

When you look at the records from the National Archives or visit the Manzanar National Historic Site, you see the remnants of gardens. The internees built rock gardens and ponds. They tried to create beauty in a place designed to strip them of their humanity.

That resilience is the real takeaway.

Practical Steps for Understanding This History

If you want to move beyond the surface level of this topic, don't just read a textbook. Textbooks are often too sanitized.

- Visit the Sites: If you are in the Western U.S., go to Manzanar (California) or Minidoka (Idaho). Feeling the wind and seeing the isolation changes your perspective.

- Dig into the Densho Project: This is the "gold standard" for archives. It’s an online repository of oral histories from survivors. Hearing a grandmother talk about the dust storms in Poston is much more impactful than reading a statistics sheet.

- Read "Farewell to Manzanar": It’s a classic for a reason. Jeanne Wakatsuki Houston’s memoir captures the sensory details of camp life that government documents leave out.

- Check Local Archives: Many West Coast cities have specific records of the property seized during the evacuation. You might be surprised to find that a building you walk past every day has a history rooted in 1942.

- Review the CWRIC Report: It’s called "Personal Justice Denied." It is a dense read, but it outlines exactly how the government ignored its own intelligence reports that showed Japanese Americans posed zero threat.

Understanding the World War Two internment camps is about recognizing the fragility of rights. It's about realizing that "citizenship" is only as strong as the people's willingness to defend it, even—and especially—when it’s unpopular. The camps closed in 1946, but the legal and social lessons they taught us are still being debated in courtrooms and on the news today. Keep looking at the primary sources. The truth is usually found in the letters and the diaries, not the official press releases.