Paper was the only thing keeping the world together between 1939 and 1945. It sounds like a reach, but it’s true. When you look at the sheer volume of World War 2 love letters that crossed the Atlantic and the Pacific, the numbers are basically staggering. We are talking about billions of pieces of mail. V-mail. Scented envelopes. Crumpled notes written in foxholes.

People didn’t just write to say "I miss you." They wrote to stay sane.

Honestly, the way we think about these letters today is a bit romanticized by Hollywood, isn't it? We imagine a soldier sitting under a tree with perfect penmanship. In reality, these letters were often stained with grease, mud, or sweat. They were censored by bored officers with black markers. They were delayed for months. Sometimes, a soldier would receive a stack of thirty letters all at once after weeks of silence, and then he’d have to read them in chronological order just to figure out if his wife had finally fixed the leaky roof or if the neighbor's kid had recovered from the flu.

The Raw Reality of V-Mail and Logistics

You've probably seen V-Mail in museums. It stands for Victory Mail. Because cargo space on planes and ships was desperately needed for ammunition and food, the military had to get creative with how they moved sentiment.

They basically turned letters into microfilm.

A person would write on a specific form, the military would photograph it, fly the tiny film reels across the ocean, and then print a miniature version of the letter for the recipient. It saved thousands of tons of weight. But it also meant that the physical touch was gone. You couldn't smell the perfume on a V-Mail. You couldn't feel the weight of the paper. It was a cold, processed version of intimacy, yet it was the most precious thing a person could own.

According to the National Postal Museum, the sheer scale of this operation required thousands of WACs (Women’s Army Corps) to sort through mountains of paper. If a letter was addressed to "Johnny Smith, US Army," it might never get there. You needed a serial number. You needed a unit. Without those, a love letter was just a ghost in the system.

What Most People Get Wrong About the Content

Most people think these letters were constant, poetic declarations of undying passion. Some were. But if you spend time in archives like the International WWII Museum in New Orleans, you realize most of them were about the mundane.

"Did you get the socks?"

"The butter ration is lower this month."

💡 You might also like: The Recipe Marble Pound Cake Secrets Professional Bakers Don't Usually Share

"I saw a movie and thought of you."

This was the "tether." Soldiers didn't want to hear about the grand strategy of the war; they wanted to hear that life back in Ohio or London was still there. They needed to know that there was a world worth returning to. The mundane was the most romantic thing imaginable because it represented peace.

The Black Marker of the Censor

Censorship was a huge deal. Every single one of these World War 2 love letters was potentially read by a stranger. Officers were tasked with reading their men's mail to ensure no one was accidentally leaking locations, ship names, or upcoming movements.

Imagine trying to be intimate when you know Captain Miller is going to read your words three days later.

It created a weird, coded language. Couples had "their" words. They used nicknames or references to old jokes to bypass the censor’s eyes. Sometimes, if a soldier mentioned he was seeing "a lot of sand lately," a heavy-handed censor would just black out the whole sentence. It was frustrating. It was lonely. It was the reality of security.

The Famous Pairs and the Anonymous Millions

We talk about the famous stuff, like the letters between Dwight D. Eisenhower and his wife Mamie. Their correspondence is a massive historical resource, showing the personal strain of command. But the real power of the World War 2 love letters phenomenon lies in the people you’ve never heard of.

Take the story of Chris and Bessie Barker. Their archive, which contains over 500 letters, shows a relationship evolving through the mail. He was a signalman; she was a member of the Postal Service herself. Their letters aren't just romantic; they are a record of social change, of a woman working a job she never thought she'd have, and a man seeing a world he never wanted to see.

Then there are the "Dear John" letters.

We can't ignore those. Not every letter was a love letter. Some were the opposite. Getting a "Dear John" was a specific kind of trauma for soldiers. In a high-stress environment where your survival often depended on your mental state, getting dumped via a three-week-old letter was devastating. It happened more than the movies like to admit.

📖 Related: Why the Man Black Hair Blue Eyes Combo is So Rare (and the Genetics Behind It)

The Physicality of the Letter

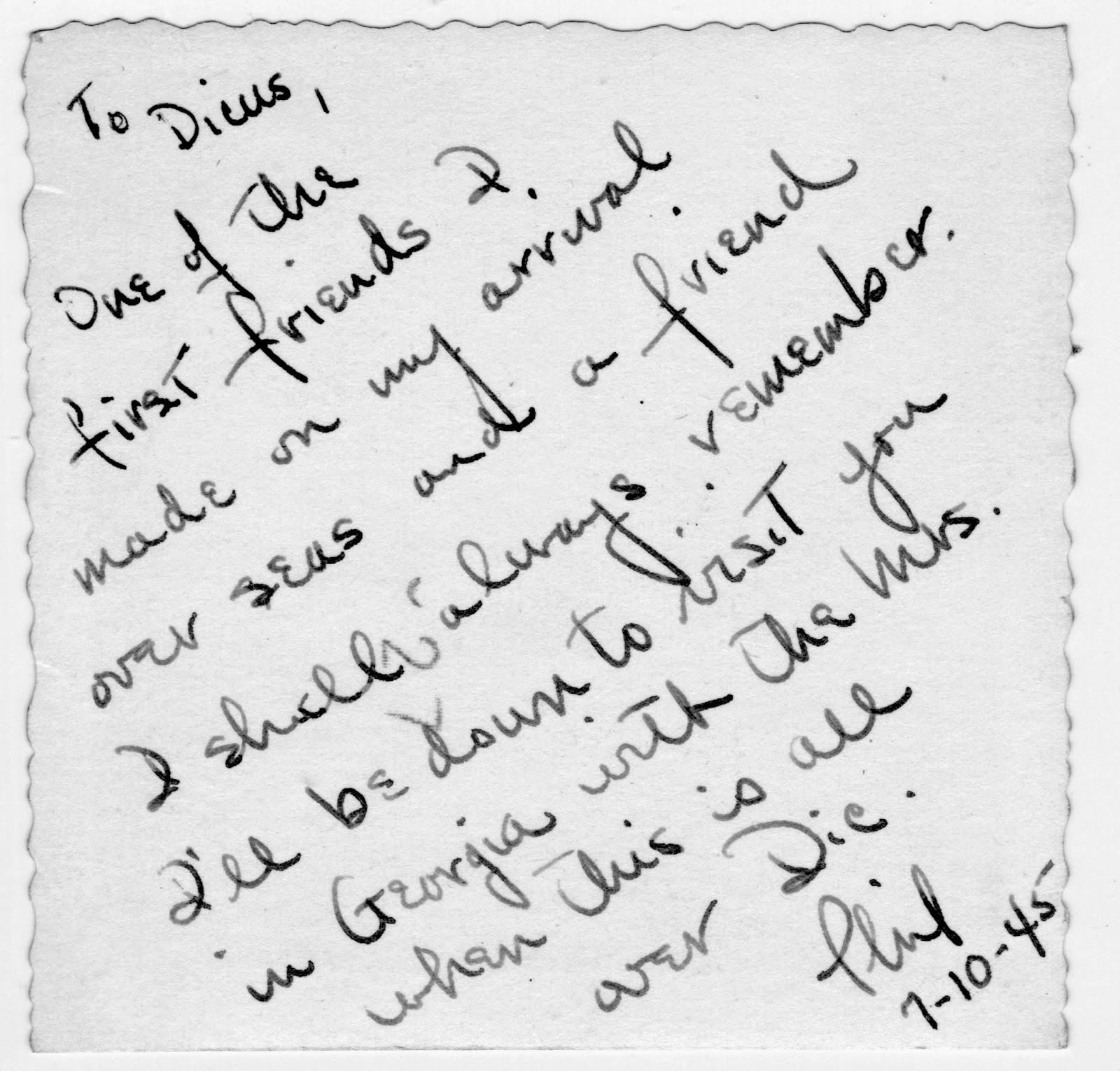

There’s something about the ink.

If you hold an original letter today—and many families still have them in shoeboxes—you can see where the pen pressed harder into the paper. You can see the shaky lines where the writer was cold or scared.

- Fountain pens were a luxury.

- Pencils were common but smeared.

- Ink was often watered down to make it last.

Digital communication can't replicate that. A text message doesn't have a "scent." During the war, women would often kiss the paper while wearing bright red lipstick. These "lipstick kisses" are still visible on letters 80 years later. It’s a physical artifact of a moment of longing. It’s a thumbprint of someone who might not have made it home.

The Psychological Weight of the Mail Call

"Mail Call" was the most important part of a soldier's day. Period.

Psychologists who study wartime morale, like those cited by the American Psychological Association, have noted that the absence of mail was a leading cause of depression and "combat fatigue" (what we now know as PTSD). A soldier who didn't get a letter for a month was a soldier who felt forgotten. And a soldier who felt forgotten was a dangerous liability to his unit.

The military knew this. They prioritized mail almost as much as ammunition. They understood that a man would fight harder if he had a fresh letter from his sweetheart in his breast pocket. It was literally a shield. Many veterans told stories of letters stopping shrapnel—though that's probably more myth than reality, the feeling of the letter being a protective charm was very real.

Why We Are Still Obsessed With These Letters

Why do we keep buying books of these? Why do TikToks of grandpas reading old letters go viral?

Because it's the peak of human sincerity.

We live in an era of "u up?" and disappearing Snaps. There is something deeply convicting about a person sitting down to write a four-page letter by candlelight, knowing it might take six weeks to arrive, and knowing they might be dead by the time the reply comes. It’s high-stakes communication.

👉 See also: Chuck E. Cheese in Boca Raton: Why This Location Still Wins Over Parents

The World War 2 love letters remind us that humans are capable of maintaining deep, complex bonds under the worst possible conditions. They show that love isn't just a feeling; it's a discipline. You had to work for it. You had to write for it.

Dealing With the Archive

If you happen to find a stash of these in an attic, don't just throw them away. Honestly, even if they aren't "famous," they are primary historical documents. Historians use these to understand everything from 1940s slang to the price of eggs during the Blitz.

- Don't use tape. If a letter is tearing, leave it. Tape will ruin the paper over time.

- Keep them out of the sun. UV light is the enemy of 1940s ink.

- Acid-free folders. If you’re serious, get the good stuff from an archival supply store.

- Scan them. Digital backups ensure the words live on even if the paper eventually crumbles.

Making the History Real

If you want to truly understand the impact of World War 2 love letters, you should look at the Legacy Project (started by author Andrew Carroll). He has collected thousands of letters from all American wars. What you notice when you read them chronologically is how the tone changes.

At the start of the war, the letters are optimistic. They talk about "knocking out the Japs" or "finishing off Hitler" by Christmas.

By 1944, the tone shifts. It gets darker. More weary. The love letters become more desperate, more focused on the "after." They stop talking about the glory of war and start talking about the glory of a quiet kitchen and a Saturday night at the pictures.

It’s the most honest history we have.

Generals write the history of the battles. The lovers write the history of the heart.

Actionable Steps for Preserving or Finding Wartime Correspondence

If you're interested in exploring this world further or have your own family history to dig through, here is how you should actually handle it:

- Visit Local Archives: Don't just look at the big national museums. Your local county historical society likely has collections of letters from people who lived in your town. Reading letters from someone who lived on your street makes the history feel much more visceral.

- Contribute to Digital Repositories: Organizations like The War Heritage Institute or The Million Veins Project often look for scans of letters to help build a more complete picture of the civilian and soldier experience.

- Contextualize the Mail: If you are reading a family letter, look up the date and the location of the unit. Matching a romantic letter to a specific battle (like the Bulge or Iwo Jima) changes how you read the "I'm doing fine" lines. Usually, they weren't fine. They were just trying to protect the person back home from the truth.

- Write Something Down: It sounds cheesy, but the reason we have this history is because people used physical media. If you want your descendants to know your story, send a letter. An email to your spouse won't be in a museum in 2090. A handwritten note might be.

The legacy of these letters isn't just in the words. It's in the fact that they survived. They are survivors of a war that tried to erase everything, proving that the need to connect is basically the most resilient thing about being human.