If you look at a standard classroom map of the world, the Pacific Ocean usually gets sliced in half. It’s tucked away on the edges, a blue fringe that makes the world look manageable. But if you want to actually understand the world war 2 in pacific map, you have to throw that flat image away. You’ve gotta realize that the Pacific is less of a "place" and more of a terrifying, endless void. It covers about one-third of the entire planet's surface. That is more than all the landmasses on Earth combined.

Everything about the Pacific Theater was dictated by this staggering, lonely distance. Logistics wasn't just a part of the war; it was the war.

When the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, they weren't just hitting a naval base. They were attempting to paralyze the only force capable of reaching across that void. Most people think of the war as a series of gritty beach landings—which it was—but looking at the world war 2 in pacific map reveals a game of leapfrog played over thousands of miles of deep water. It’s honestly hard to wrap your head around how a supply sergeant in San Francisco was supposed to get a fresh crate of eggs or a replacement carburetor to a guy on a tiny coral atoll 6,000 miles away.

The Strategy of Distances

The Japanese Empire's strategy, often called the "Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere," was basically a giant defensive perimeter. They grabbed Malaysia for the rubber, Indonesia (then the Dutch East Indies) for the oil, and then tried to build a "ribbon" of fortified islands to keep the Americans out. They figured the U.S. would get tired. They thought we'd look at the map, see the thousands of miles of blue, and just say, "Nah, not worth it."

But they didn't account for "Island Hopping."

👉 See also: The Truth About Mamma Mia Island Greece: What Most People Get Wrong

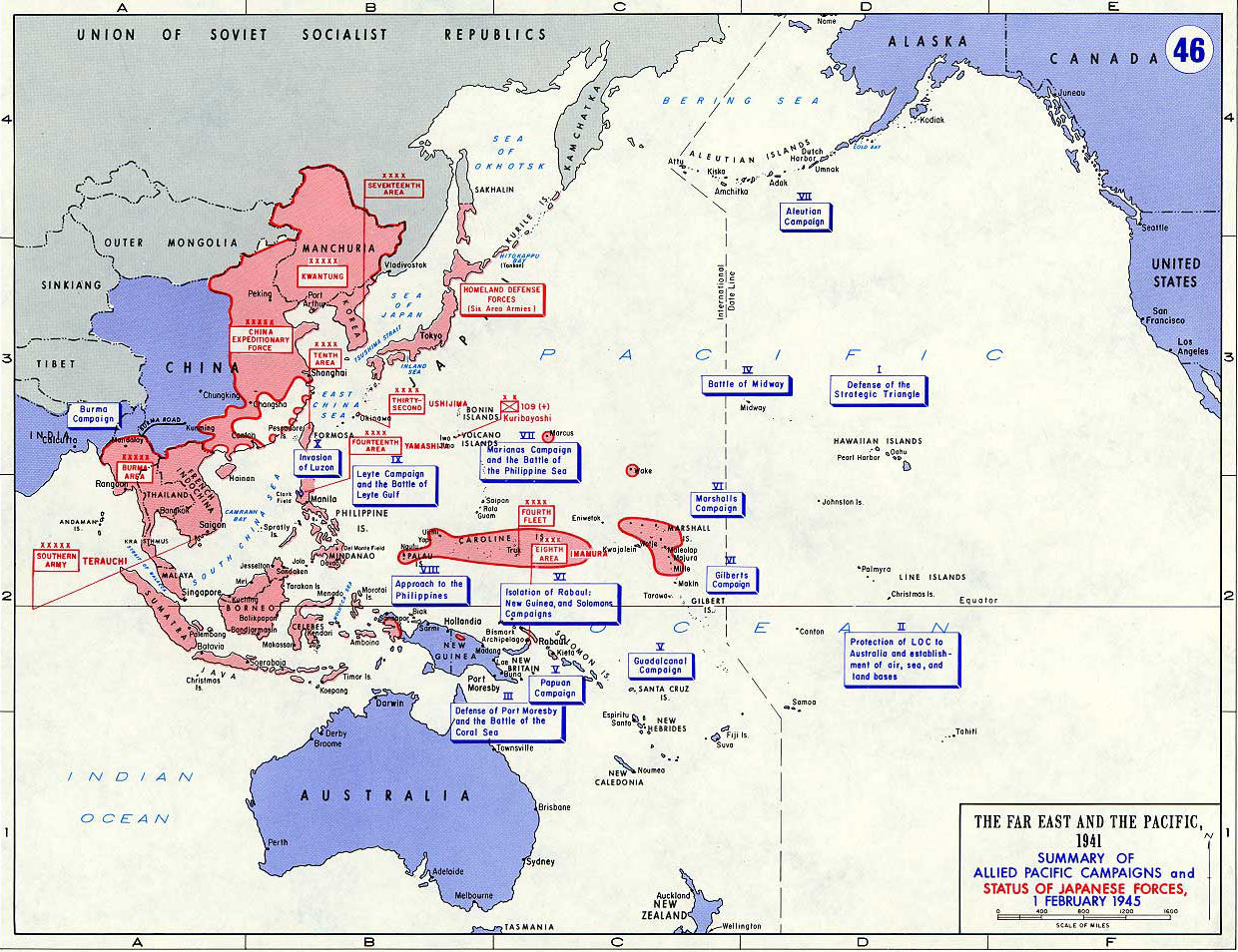

Admiral Chester Nimitz and General Douglas MacArthur didn't try to take every single island. That would’ve been suicide. Instead, they looked at the world war 2 in pacific map and picked specific targets—the ones with airfields or deep-water harbors. If an island had 5,000 Japanese soldiers on it but no runway? The U.S. just sailed right past it. They left those soldiers to "wither on the vine." It’s a brutal way to win a war. You don't kill the enemy; you just make them irrelevant by moving the map three hundred miles past them.

The Logistics of the "Big Blue"

Let's talk about the "Line of Communication." In Europe, you could often find a train or a road. In the Pacific? There are no roads. Everything moves by hull.

Take the Battle of Guadalcanal. It’s this jungle-choked island in the Solomons. If you look at it on a map today, it looks like a tropical paradise. In 1942, it was the end of the world. The U.S. Marines landed there, but the Navy got pushed back in the Battle of Savo Island. For a while, those Marines were totally cut off. On the world war 2 in pacific map, the distance from Guadalcanal back to a major base like Pearl Harbor is roughly 3,600 miles. To put that in perspective, that is further than the distance from New York City to London.

Imagine fighting a war where your "local" grocery store is across the Atlantic Ocean.

- The Southern Route: Managed mostly by MacArthur, moving through New Guinea toward the Philippines.

- The Central Pacific Drive: Led by Nimitz, hitting the Gilbert Islands, the Marshalls, and the Marianas.

- The Forgotten Front: The China-Burma-India theater, where the "map" was mostly jagged mountains and impenetrable jungle.

It wasn't a single line of advance. It was a multi-pronged squeeze. By 1944, the U.S. was building "floating bases." They had massive concrete barges that acted as floating refrigerators, mobile dry docks that could fix a destroyer in the middle of the ocean, and even a floating post office. They literally moved the infrastructure of a medium-sized American city across the map.

Why the Marianas Changed Everything

If you’re staring at a world war 2 in pacific map, find Saipan, Tinian, and Guam. They are tiny specks. But in 1944, they were the most important real estate on Earth. Why? Because of the B-29 Superfortress.

Before the U.S. took the Marianas, Japan was mostly out of reach for heavy bombers. But once the "Seebees" (Construction Battalions) built massive runways on Tinian, the map changed. Japan was now within a 1,500-mile radius. That sounds like a lot, but for a B-29, it was a commute. This is where the tactical map becomes a strategic nightmare for the home islands of Japan.

The firebombing of Tokyo and eventually the atomic missions started from those tiny specks on the map. It’s wild to think that the fate of the world was decided on a piece of coral that most people couldn't find with a magnifying glass today.

Misconceptions About the Terrain

People usually picture "The Pacific" as one big beach. Sorta like a deadly version of a Sandals resort.

That is totally wrong.

The world war 2 in pacific map covers everything from the Aleutian Islands in Alaska—which are foggy, freezing, and miserable—to the volcanic ash of Iwo Jima, where the ground was literally hot to the touch because of geothermal activity. In New Guinea, soldiers fought in rainforests so thick they couldn't see the sun for days. Disease killed more people than bullets in some of these places. Malaria, dengue fever, and "jungle rot" were constant map-side companions.

It was also a war of verticality. On islands like Okinawa, the Japanese didn't fight on the beaches. They dug into the ridges. They turned the geography itself into a weapon. The map wasn't just X and Y coordinates; it was the depth of the caves and the height of the escarpments.

The Legacy Left Behind

Today, if you travel to these places, the war is still there. It’s weirdly haunting. You can go to Chuuk Lagoon (formerly Truk) and dive on an entire Japanese fleet sitting at the bottom of the ocean. It’s the world’s largest underwater graveyard. You can see tanks rusting into the sand on Peleliu.

The world war 2 in pacific map isn't just a historical document; it's a graveyard of ships and planes that were simply too far from home to ever be recovered.

Most of the islands that saw the heaviest fighting—Tarawa, Eniwetok, Kwajalein—have returned to being quiet, remote outposts. But the scars are permanent. The airfields built by the U.S. are often still the main airports for these island nations. The geography of the war literally created the modern infrastructure of the Pacific.

How to Actually Study the Pacific Map Today

If you really want to get a feel for this, don't just look at a map in a book. Go to Google Earth.

🔗 Read more: Driving Distance Columbia SC to Myrtle Beach SC: What Your GPS Won't Tell You

- Measure the distances. Use the ruler tool to measure from San Francisco to Manila. It will blow your mind.

- Look at the atolls. Zoom in on Midway or Wake Island. See how small they are? Now imagine 50,000 men trying to kill each other on that tiny strip of sand.

- Trace the "Hump." Look at the mountains between India and China. Imagine flying a cargo plane over those in 1943 without modern GPS.

- Check the "Iron Bottom Sound." Look at the waters off Guadalcanal. It’s named that because so many ships sank there that it actually affects compass readings.

The sheer scale of the Pacific Theater is the most underrated aspect of the conflict. We focus on the heroism and the tragedy, as we should. But we often forget the math. The war was won by the side that could best solve the impossible geometry of the Pacific Ocean.

To get a true sense of the logistics involved, look into the "Service Force, Pacific Fleet." These were the guys who made sure the map stayed red, white, and blue by delivering millions of gallons of fuel and tons of ammunition to the middle of nowhere. It’s not as "cool" as a fighter pilot's story, but it’s why the map looks the way it does today.

If you’re planning a trip to see these sites, start with the National World War II Museum in New Orleans or the Arizona Memorial in Hawaii. They provide the best context before you head out to the more remote islands. Just remember, once you leave Hawaii, you’re heading into a part of the world where the horizon never ends.