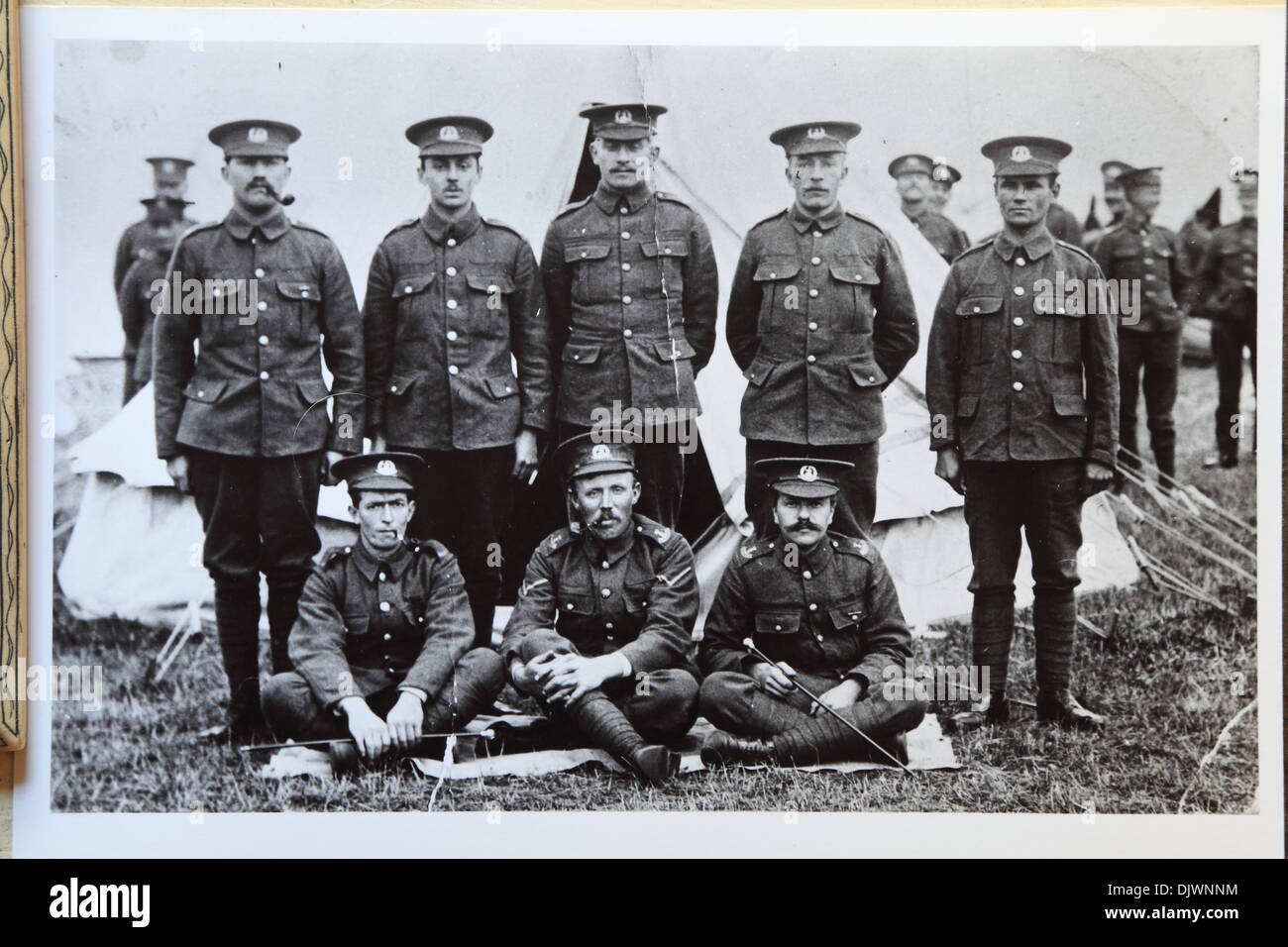

Look at them. Really look. Most people swipe past old black-and-white photos thinking they’re just dusty relics of a bygone era, but world war 1 soldiers pictures are actually high-definition windows into a world that was screaming. You see the stiff collars and the polished buttons, sure. But if you lean in, you see the "thousand-yard stare" before there was even a name for it. It's haunting.

The Great War was the first conflict where the camera actually went to the front lines in a meaningful way. Before this, war photography was mostly posed portraits or shots of empty battlefields after the bodies were cleared. Then 1914 happened. Suddenly, pocket-sized cameras like the Vest Pocket Kodak—advertised as "The Soldier's Kodak"—started appearing in the trenches. It changed everything.

Why world war 1 soldiers pictures look so "stiff" (and why they aren't)

There is this common misconception that people back then were just naturally more formal or lacked a sense of humor. That’s total nonsense. Honestly, the reason they look like statues in many world war 1 soldiers pictures is purely technical.

Even by 1914, shutter speeds were getting faster, but in low-light environments like a dugout or a muddy trench under a grey French sky, you still had to hold still. If you moved, you were a blur. So, you get these rigid, unblinking expressions. But look at the unofficial shots—the "trench art" of photography. You'll see soldiers goofing off, wearing captured German helmets, or holding onto scrawny stray dogs they adopted as mascots.

Those candid moments are where the real history lives.

The Kodak ban and the rise of the "outlaw" photographer

Did you know it was actually illegal for most British soldiers to take photos? By 1915, the War Office realized that a single photo of a pile of bodies or a flooded trench could destroy morale back home. They banned personal cameras. They wanted controlled, sanitized images from official photographers like Ernest Brooks.

But soldiers are soldiers. They smuggled those little Kodaks in their kits anyway. Many of the most gut-wrenching world war 1 soldiers pictures we have today were technically "contraband." If a soldier was caught, they faced a court-martial. Think about that for a second. Men were risking military prison just to document the reality of their lives. That tells you how much they wanted to be seen.

✨ Don't miss: Franklin D Roosevelt Civil Rights Record: Why It Is Way More Complicated Than You Think

Identifying the details in the uniform

If you're looking at a family heirloom and trying to figure out what you're seeing, the devil is in the details. It's basically a puzzle.

- The Puttees: Those long strips of cloth wrapped around the legs? They were a nightmare. They were supposed to provide support and keep mud out of boots, but if wrapped too tight, they cut off circulation. In many photos, you can see soldiers wearing them haphazardly—a sign of a "veteran" who cared more about comfort than drill-sergeant perfection.

- The P08 Leather Gear: British soldiers wore "webbing" made of canvas. If you see a soldier in a photo wearing leather equipment that looks like the canvas version, he’s likely part of a reserve unit or training in the UK. Leather was the backup because the factories couldn't keep up with the demand for canvas.

- The "Soft" Cap vs. The Brodie: Before 1916, most guys were wearing felt caps. Basically zero protection. If your world war 1 soldiers pictures show men in steel helmets (the "Brodie" or "Tommy" helmet), you’re almost certainly looking at a photo from late 1915 or later.

The psychological weight of the studio portrait

When a soldier knew he was going "over the top" or heading to the front, he often went to a professional studio in a local French or British village. This was the "just in case" photo.

These portraits are weirdly clean. The soldier has probably spent a week scrubbing mud off his uniform. He’s standing in front of a painted backdrop of a peaceful forest or a grand library. It’s a lie, basically. But it was a kind lie meant for his mother or his wife. He wanted them to remember him as a hero, not as a man living in a hole in the ground with rats the size of cats.

Experts like those at the Imperial War Museum (IWM) have archived millions of these. When you compare a studio portrait to a "trench candid," the difference in the eyes is staggering. In the studio, there's hope. In the trench, there's just... existence.

Colorization: Does it help or hurt?

There is a huge debate among historians about colorizing world war 1 soldiers pictures. You’ve probably seen Peter Jackson’s They Shall Not Grow Old. It’s a masterpiece. By adding color and correcting the frame rate, he turned "ghosts" into living people.

Some purists hate it. They think it distorts the original historical record. But honestly? Most people find it easier to empathize with a face that isn't grey. When you see the actual shade of the "Khaki" (which was more of a mustard-brown) and the bright red of a fresh poppy, the war stops being a movie and starts being a memory.

🔗 Read more: 39 Carl St and Kevin Lau: What Actually Happened at the Cole Valley Property

The "Ghost" images of the fallen

There is a specific type of photo that is particularly heartbreaking. Occasionally, you'll find a photo where a soldier looks translucent. This wasn't a ghost, obviously. It was a long exposure where the soldier moved or walked away before the shot was finished. In the context of a war where millions disappeared into the mud of the Somme or Passchendaele, these "accidental" ghosts feel incredibly symbolic.

How to preserve your own world war 1 soldiers pictures

If you’ve got these photos in a shoebox, you’re holding onto something that is literally decomposing. Silver gelatin prints are tough, but they aren't invincible.

- Stop touching the surface. The oils on your fingers are acidic. They will eat the image over decades. Handle them by the edges or wear cotton gloves if you want to be a pro about it.

- Scan at high DPI. Don't just take a photo of the photo with your phone. Use a flatbed scanner. Set it to at least 600 DPI (1200 is better). This allows you to zoom in on things like shoulder flashes or cap badges that help identify the unit.

- No sunlight. UV rays are the enemy. If you want to display a photo of a Great War ancestor, make a high-quality copy and frame that. Keep the original in a dark, acid-free sleeve.

The reality of the "Death Penny" and commemorative photos

Often, world war 1 soldiers pictures are found tucked into frames with a large bronze disk. This was the "Next of Kin Memorial Plaque," colloquially called the "Death Penny." Over 1.3 million were issued to the families of those who died.

Finding a photo paired with this disk changes the context entirely. It’s no longer just a military record; it’s a shrine. Families would often take the soldier's last letter and tuck it behind the photo in the frame. If you're researching an old photo, always check the back of the frame. You might find "trench letters" that haven't seen the light of day in a century.

Researching the man in the photo

If you have a photo but no name, don't give up. It’s a slog, but you can find them.

Check the cap badge first. That tells you the regiment. Then, look for "Service Stripes" on the lower sleeves. Each chevron usually represented a year of service overseas. Wound stripes (vertical gold braid) tell you if he was hit.

💡 You might also like: Effingham County Jail Bookings 72 Hours: What Really Happened

Once you have a regiment and a name, sites like Ancestry or the Commonwealth War Graves Commission (CWGC) become your best friends. You can often match a face to a "Medal Roll" index card. It’s like CSI: 1914.

Identifying fakes and "Great War" style recreations

Nowadays, with the rise of reenacting and AI, you have to be careful. Some "world war 1 soldiers pictures" floating around social media are actually stills from movies or modern reenactors using sepia filters.

Real photos usually have a "matte" or "eggshell" texture if they are original prints. They often have the photographer's stamp on the back from a town in France (like Amiens or Étaples). If the uniform looks too perfect—no fraying, no dirt, no mismatched buttons—be skeptical. The real war was messy.

What to do next with your collection

Don't let these images sit in the dark. History is only useful if it's shared.

- Digitize and Donate: Contact local museums. They might not want the physical copy, but they often want the high-res scan for their digital archives.

- Geotag the History: If you know where the photo was taken (check for landmarks in the background), you can contribute it to projects like "Lives of the First World War."

- Write it down: If you know the name of the man in the photo, write it on the back of the frame or the sleeve in pencil (never ink—ink bleeds). The biggest tragedy is a hero becoming "Anonymous."

These pictures aren't just art. They're a debt we haven't quite finished paying. Every time you look at a soldier's face from 1916, you're keeping a promise that their sacrifice wouldn't be forgotten.

Scan your photos this weekend. Seriously. Don't wait for the paper to crumble or the silver to fade. Those faces deserve more than a shoebox in the attic.