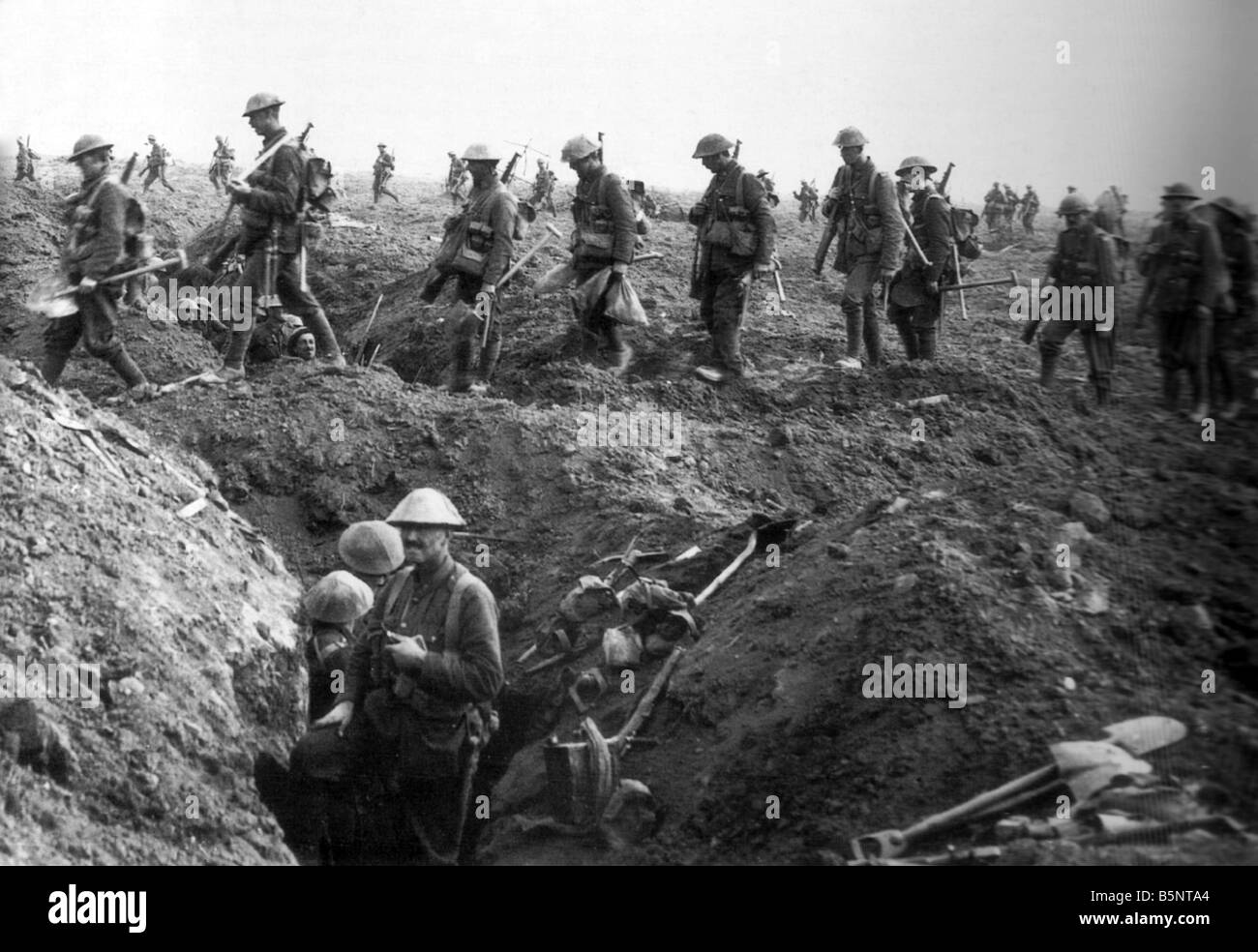

When you think of World War 1 soldiers in trenches, your mind probably goes straight to the mud. You imagine the whistles blowing and men leaping over the top into a hail of machine-gun fire. It's the Hollywood version. It's 1917 or All Quiet on the Western Front. But the reality? Honestly, it was a lot more boring, a lot more disgusting, and much weirder than the movies ever let on.

Most of the time, they weren't fighting. They were just... existing.

Imagine living in a ditch for weeks. Now, make that ditch three feet wide and filled with a foot of standing water that smells like a mix of rotting onions, unwashed bodies, and chloride of lime. That was the daily grind. It wasn't just about the enemy across the way; it was about surviving the very ground you were standing on.

What No One Tells You About the Trench Daily Routine

The "Morning Stand-To" was the start. It happened just before dawn because that’s when the generals thought an attack was most likely. Everyone climbed up onto the fire step, bayonets fixed, staring into the mist of No Man's Land. But once the sun was up? It was time for the "Morning Hate." This was basically just both sides firing off a few rounds of artillery or rifles just to say, "Hey, we're still here, don't try anything."

After that, it was breakfast. If you were lucky, you got bacon. If you weren't, it was hard biscuits that could literally break a tooth.

The rest of the day was mostly chores. You've gotta remember, trenches weren't permanent stone structures. They were basically holes in the dirt. They were constantly collapsing. Soldiers spent hours filling sandbags, "reveting" the walls with wire or wood, and pumping out water. If you stopped digging, the trench disappeared. It was a never-ending battle against gravity and rain.

By the time night fell, the real work started. Night was when the supplies came up. It was when "shoveling parties" went out to fix the wire. It was also when "listening posts" were set up—men crawling out into the dark, sitting in a shell hole, and literally just listening for the sound of German shovels or whispers.

The Great Rat Problem

You can’t talk about World War 1 soldiers in trenches without talking about the rats. This isn't just a "gross detail" for history books; it was a genuine psychological horror. These weren't your average city rats. These things grew to the size of small cats because they were feeding on, well, the dead.

💡 You might also like: Human DNA Found in Hot Dogs: What Really Happened and Why You Shouldn’t Panic

Soldiers would try to hunt them with bayonets or even fire their rifles at them, which was technically against the rules because it wasted ammo. One soldier, George Coppard, wrote in his memoirs about how the rats would run across your face while you slept. They’d eat the leather off your equipment. They’d get into your rations. It was a constant, skittering reminder of the carnage around you.

Why the Design of the Trench Mattered

Most people think of a trench as a straight line. It wasn't. If you built a straight trench, one guy with a machine gun at the end could wipe out the whole line. Instead, they were built in a "zigzag" or "crenelated" pattern. This meant that if a shell landed in the trench, the blast would be contained by the next corner.

It also meant you could never see more than about ten yards in either direction. It was incredibly claustrophobic. You were trapped in a maze.

There were actually three "lines" of trenches:

- The Front Line: Where the actual fighting happened.

- The Support Line: About 70 to 100 yards back, where men could retreat if the front was taken.

- The Reserve Line: Even further back, where the "off-duty" troops waited.

Soldiers didn't spend the whole war in the front line. Usually, they'd do maybe four days in the front, four in support, four in reserve, and then a few days of actual rest in a nearby village. But "rest" was a relative term. You were still being shelled, and you were probably still sleeping in a barn.

The Psychological Toll of the "Shell"

We call it PTSD now. Back then, it was "Shell Shock."

Dr. Charles Myers was one of the first to really study this during the war. He realized that it wasn't just about the physical impact of explosions. It was the constant, low-level stress of knowing you could be deleted from existence at any second. Imagine sitting in a hole while heavy metal rain falls for six hours straight. You can't run. You can't hide. You just wait.

📖 Related: The Gospel of Matthew: What Most People Get Wrong About the First Book of the New Testament

Some men went catatonic. Others couldn't stop shaking. At first, the military brass thought they were just being cowards. They even executed some men for "desertion" who were clearly suffering from severe psychological trauma. It was a brutal misunderstanding of how the human brain works under pressure.

Living Conditions: Lice, Trench Foot, and Bad Food

If the shells didn't get you, the hygiene might. World War 1 soldiers in trenches dealt with "trench fever," which was eventually traced back to lice. These lice—"chats," they called them—lived in the seams of your clothes. Men would spend their free time with a candle flame, running it along the seams of their trousers to pop the lice eggs. It was a never-ending cycle.

Then there was Trench Foot.

This was a fungal infection caused by feet being wet for days or weeks on end. Your feet would turn red or blue, go numb, and eventually start to rot. If it got bad enough, they had to amputate. The only way to prevent it? Whale oil. Officers would literally force men to rub whale oil on each other's feet to create a waterproof barrier. It sounds weird, but it saved thousands of limbs.

And the food?

- Maconochie's Meat Stew: Mostly fat and gristle.

- Bully Beef: Canned corned beef that got real old, real fast.

- Hardtack Biscuits: So hard they were often ground up and mixed with water to make a kind of "porridge."

- Tea: Usually made with water that had been carried up in old petrol cans, so it always tasted like gasoline.

The Myth of No Man's Land

We picture No Man's Land as a flat, empty space. It was actually a chaotic graveyard of rusted wire, unexploded shells, and deep craters filled with green, stagnant water. Sometimes, after heavy rain, the mud became so thick that men actually drowned in it. It wasn't just a metaphor. Men like Private Edward Lynch described seeing comrades slip into shell holes and simply vanish because they were weighed down by 60 pounds of gear.

Communication was a nightmare too. No cell phones, obviously. Radios were huge and clunky. They used pigeons. They used runners—guys whose entire job was to sprint through the mud with a piece of paper. Most of them didn't make it. If you ever wonder why WWI battles seemed so disorganized, that’s why. The generals were miles behind the lines, and by the time they knew what was happening, the situation had already changed.

👉 See also: God Willing and the Creek Don't Rise: The True Story Behind the Phrase Most People Get Wrong

What Most People Get Wrong About the "Over the Top" Attacks

The image of thousands of men charging all at once is mostly from the early part of the war, like the Somme in 1916. By 1918, things had changed. They started using "Creeping Barrages."

The idea was that the artillery would fire just a few hundred yards ahead of the infantry. As the soldiers moved forward, the artillery fire moved forward too. It was a "wall of steel" that protected the soldiers. But it required perfect timing. If the soldiers moved too slow, the enemy machine gunners had time to come out of their bunkers. If they moved too fast, they walked right into their own shells.

Actionable Insights: How to Learn More Authentically

If you really want to understand what it was like for World War 1 soldiers in trenches, you have to stop looking at the polished history books and start looking at the primary sources. History is best served raw.

- Read the Diaries: Forget the textbooks. Read Poilu by Louis Barthas or Storm of Steel by Ernst Jünger. These are first-hand accounts that don't care about "the big picture"—they care about the mud and the soup.

- Visit the "Quiet" Sites: If you ever go to France or Belgium, don't just go to the big monuments. Go to the smaller, preserved trench sites like Sanctuary Wood (Hill 62) near Ypres. You can still see the undulations in the ground where the shells hit.

- Listen to the Voices: The Imperial War Museum (IWM) has an incredible online archive of recorded interviews with veterans from the 1960s and 70s. Hearing a 90-year-old man's voice crack when he talks about his "mate" from 1916 is more impactful than any movie.

- Study the Poetry: It sounds cliché, but Wilfred Owen and Siegfried Sassoon weren't writing "art." They were writing protest letters from the dirt. Dulce et Decorum Est is basically a GoPro video in word form.

The war wasn't just a series of dates. It was a millions of individual lives being lived in a very long, very wet ditch. Understanding that human element is the only way to truly respect what those men went through.

Next Steps for Deeper Research:

- Check out the Commonwealth War Graves Commission (CWGC) database to look up specific names if you have ancestors who served.

- Explore the "Great War" YouTube channel for a week-by-week breakdown of the conflict.

- Analyze the evolution of small unit tactics from 1914 to 1918 to see how the "trench deadlock" was eventually broken by tanks and coordinated infantry.

The trench was a world of its own—a brutal, filthy, and strangely organized society that changed the course of the 20th century. By looking past the myths, we start to see the people who actually lived there.