You’ve probably seen it on a dozen HR forms or payroll calculators. 260. That is the magic number everyone points to when they talk about how many days you’re supposed to be at your desk. It feels official. It feels solid. But honestly? It’s almost never actually right.

Calculating work days per year is one of those things that seems like a third-grade math problem until you actually start looking at a calendar. Then, everything gets messy.

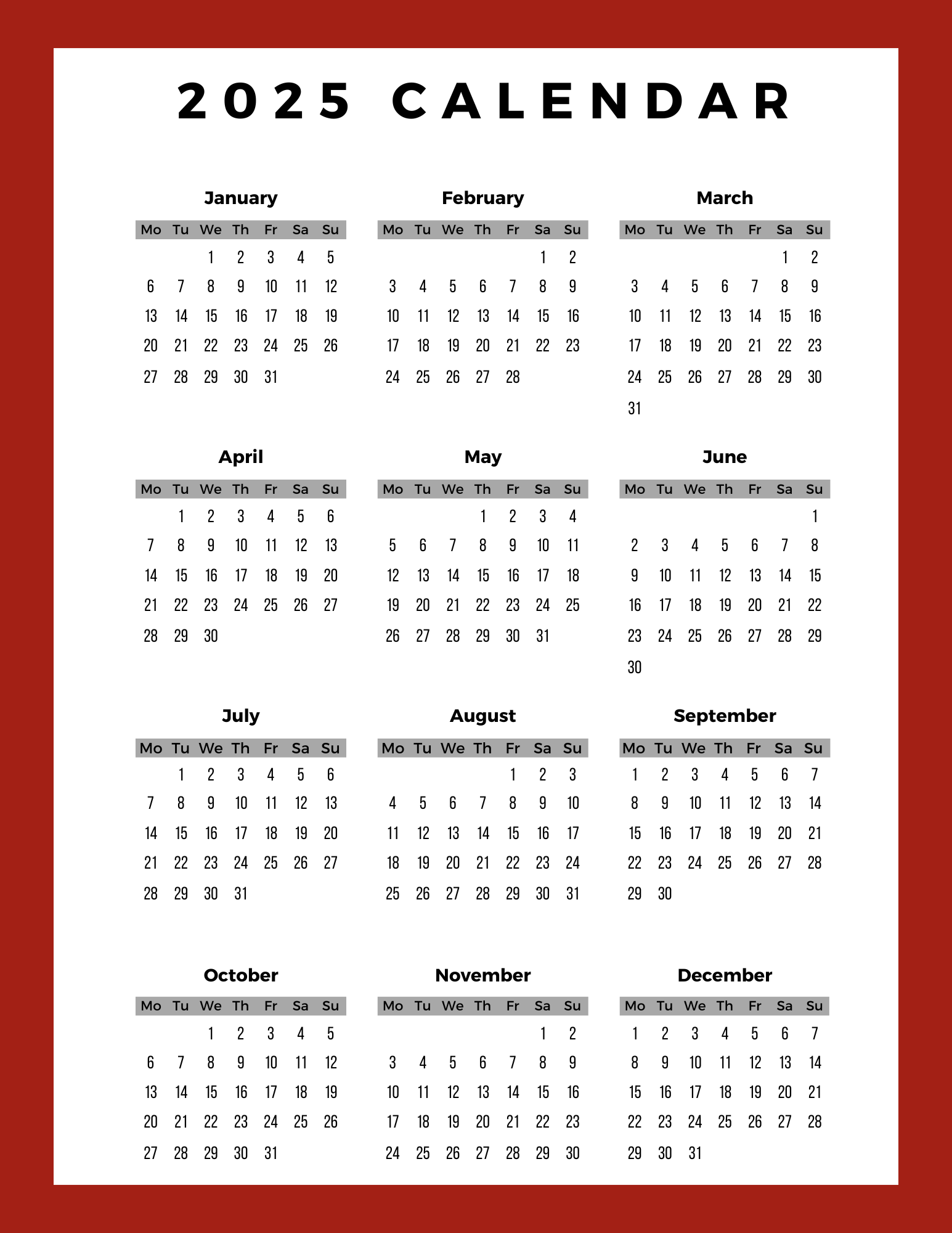

Leap years happen. Federal holidays move around. Weekends fall on weird dates. If you're trying to figure out your hourly rate or plan a project budget, relying on a generic average is a great way to lose money or miss a deadline. Most people just divide 365 by seven and multiply by five. That gives you 260.71. But you can't work 0.71 of a day unless you're in a very specific type of gig economy hell.

The calendar math that breaks your brain

The reality is that every single year is different. 2024 was a leap year, which meant 366 days. 2025 and 2026 are "standard" years. Because a year isn't exactly 52 weeks—it's 52 weeks plus one day (or two in a leap year)—the number of Mondays, Tuesdays, and Wednesdays fluctuates. This is why some years feel longer. They literally are.

If a year starts on a Saturday, you get more weekend days. If it starts on a Monday, you're looking at a heavy workload. For example, in a standard 365-day year, there are 261 work days if the year starts on a weekday, but only 260 if it starts on a weekend. It sounds like a small difference. It isn't. For a company with 500 employees, that one extra day represents thousands of hours in productivity or payroll costs.

Most businesses in the U.S. base their calculations on the GAO (Government Accountability Office) standard or the OPM (Office of Personnel Management) guidelines. They use a 2,087-hour work year for federal employees. Why that specific number? It accounts for the fact that every 28 years, the calendar repeats exactly, and the average number of work hours per year over that cycle is 2,087.

Holidays and the "Hidden" Vacation Tax

We haven't even touched on holidays yet. You aren't actually working 260 days. Nobody is.

🔗 Read more: socialsecurity gov social security: What Most People Get Wrong About Using the Site

The Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) consistently tracks "employee benefits," and for the average private industry worker, you're looking at about 8 paid holidays per year. If you're in the public sector, that number usually jumps to 11 or 12. Then you have to bake in Paid Time Off (PTO). According to Zippia’s data aggregation, the average American worker gets about 10 days of PTO after one year of service.

Let's do some quick, ugly math.

Start with 261 potential work days. Subtract 11 federal holidays. Subtract 10 days of vacation. Subtract maybe 5 sick days because, let’s be real, everyone gets the flu eventually. Suddenly, your "work days per year" dropped from 261 to 235. That is a massive difference. If you're a freelancer or a contractor, and you haven't accounted for those 26 missing days in your day rate, you’re basically giving yourself a 10% pay cut without realizing it.

The Global Perspective: Why the US is an Outlier

It's sort of wild how much this changes once you cross an ocean. If you think 260 sounds like a lot, don't look at the stats for Mexico or South Korea, where the work culture often pushes those numbers significantly higher due to shorter vacation mandates.

On the flip side, look at France or Germany. In France, the legal work week is 35 hours. While they still have a similar number of calendar days, their "total hours worked" per year is drastically lower than in the U.S. or Japan. According to the OECD, the average American works about 1,811 hours per year. The average German? About 1,340.

That is a gap of nearly 500 hours.

That’s basically 60 full work days. Imagine having two extra months of life back every year. This is why international companies struggle so much with project management. You can’t just apply a "standard" work year template to a global team. You’ll end up with a project that is two months behind before it even starts.

The Leap Year Glitch

Leap years are the gremlins of the payroll world. Every four years, we add February 29th. If that day falls on a weekday, salaried employees are technically working an extra day for free.

Most employment contracts are based on an annual salary, not a daily rate. If your salary is $70,000, you get paid the same whether the year has 260 work days or 262. In 2024, many workers realized they were putting in an extra eight hours of labor compared to 2023 for the exact same paycheck.

Some labor unions have actually fought for "leap year bonuses" or adjusted pay scales, though it's rare. Usually, the company just wins that extra day of productivity. It’s one of those weird quirks of the Gregorian calendar that we’ve all just agreed to ignore because fixing it would require a level of accounting math that would make everyone’s head explode.

How to Calculate Your Actual Work Days

If you want to be precise, stop using the 260 rule. It’s lazy. Instead, follow this messy but accurate process for the current year.

- Count the total days. Start with 365 (or 366).

- Remove the weekends. Look at the calendar. How many Saturdays and Sundays are there? It’s usually 104 or 105.

- Subtract the "Hard" Holidays. These are the ones your office is definitely closed for (New Year's, Memorial Day, July 4th, Labor Day, Thanksgiving, Christmas).

- Subtract your personal "Floaters." This is your PTO, your "mental health days," and your sick leave.

What you're left with is your Actual Capacity.

For most professionals, that number is going to land somewhere between 220 and 230. That is the number you should use for your personal productivity planning. If you try to cram 260 days' worth of work into a year where you're only physically present for 225, you are going to burn out by October. It’s just physics.

The Problem with "Productivity" Metrics

We talk about work days as if every day is equal. It isn't.

There's this concept called "The Wall." Usually, it hits around late November. Between Thanksgiving and New Year's, the "effective" work days per year take a massive hit. Even if people are at their desks, the output drops. Research from the Draugiem Group found that the most productive employees don't actually work 8-hour days; they work in sprints.

If we measure our lives by "days worked," we’re using a metric from the industrial revolution. Back then, if you weren't standing at the assembly line, the widget didn't get made. Today, for knowledge workers, the "day" is a terrible unit of measurement. One highly focused Tuesday where you solve a major technical bug is worth more than a dozen "work days" spent sitting in circular meetings.

Actionable Steps for Managing Your Year

Stop treating the calendar like a static block. It’s a resource.

First, go into your digital calendar right now and block out all the federal holidays for the next 12 months. Don't wait for the week of. Seeing those "greyed out" blocks will give you a more honest view of how much time you actually have to finish that big project.

Second, if you're a freelancer, take your desired annual income and divide it by 220, not 260. That is your true daily rate. If you use 260, you aren't accounting for the fact that you need to eat and sleep and occasionally go to the dentist.

Third, audit your "ghost days." These are days where you are technically working but essentially useless—like the day after a cross-country flight or the Friday before a major holiday. If you can identify those 10-15 ghost days, you can stop scheduling important work during them.

The 260-day work year is a myth used to simplify accounting. It doesn't exist in nature. Once you start planning around the 225-230 days you actually have, the stress of "running out of time" starts to fade. You aren't lazy; you're just finally counting correctly.

To get ahead of your schedule, calculate your specific billable hours for the next quarter by subtracting exactly three days for "unforeseen interruptions"—because those always happen—and see how that changes your perception of your upcoming deadlines. It’s usually a wake-up call.