It is November 1963. Beatlemania isn't just a buzzword; it’s a literal medical phenomenon in the UK. Screaming teenagers, police barricades, the whole bit. Most bands in this position would have crumbled under the pressure of the "sophomore slump." Instead, John, Paul, George, and Ringo walked into EMI Studios and hammered out With The Beatles.

People often treat this record as a bridge. A stepping stone between the raw energy of Please Please Me and the world-changing art of A Hard Day’s Night. That’s a mistake. Honestly, if you really listen to it, this is the moment the Beatles stopped being a cover band from Liverpool and started becoming the architects of modern pop music.

The Pressure Cooker of 1963

You have to understand the timeline. They released their debut in March. By the summer, they were essentially prisoners of their own fame. They didn't have months to "find their muse" or go on a spiritual retreat to write. They had gaps in a grueling touring schedule. They had four days. That's it.

The sessions for With The Beatles were scattered between July and October. Think about that. They were playing shows, recording BBC radio sessions, and filming TV appearances, all while trying to figure out how to follow up a number one album. It was chaotic. It was loud. It was perfect.

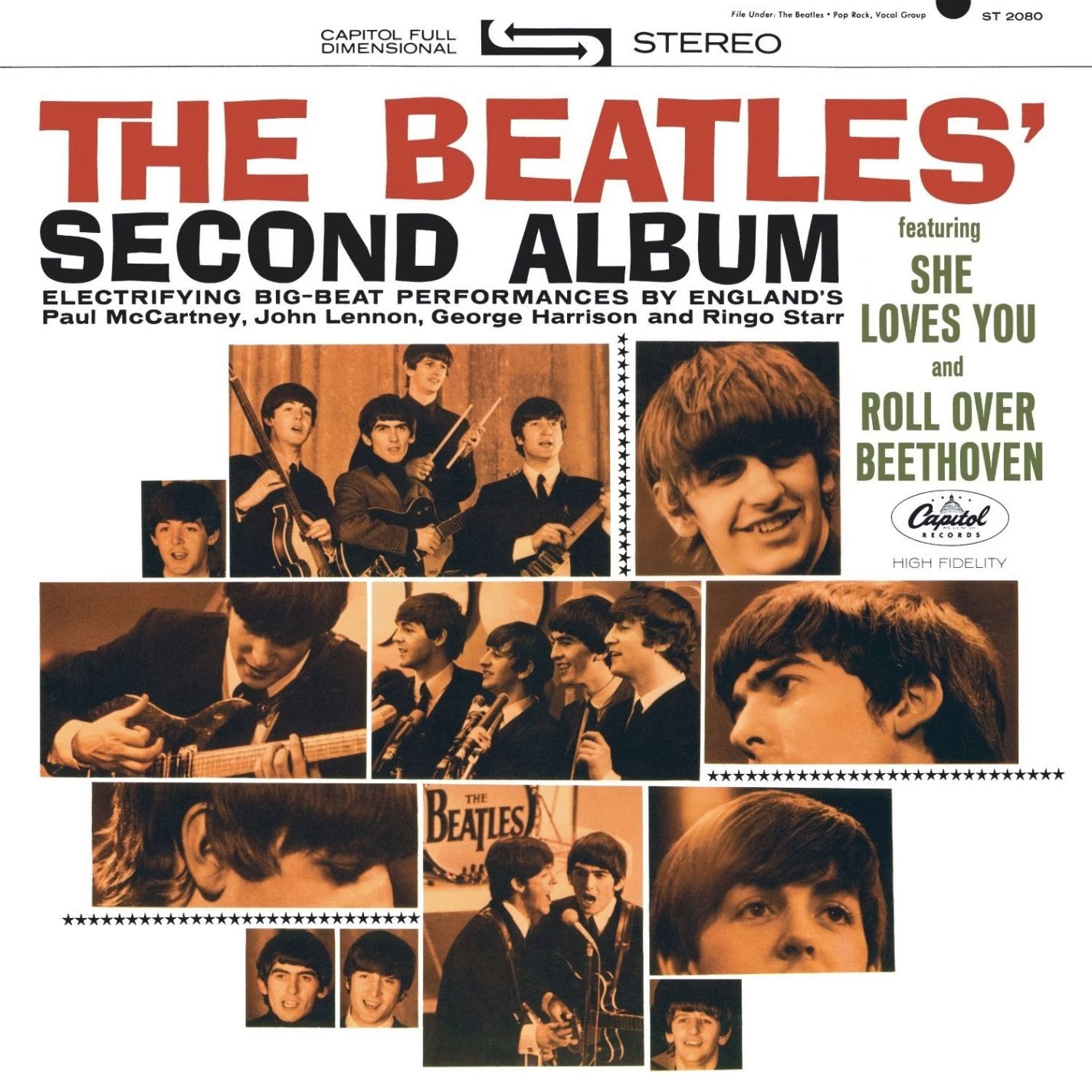

Most critics point to the cover art first. Robert Freeman took that iconic high-contrast, half-shadow photo in a dark hallway at the Palace Court Hotel in Bournemouth. It looked moody. It looked serious. It didn't look like the smiling, waving boys from the first album cover. This was a statement of intent: we aren't just entertainers; we are artists. Even the lack of the band's name on the front cover—just the title and those four faces—was a revolutionary move by EMI's standards at the time.

📖 Related: Liam Hemsworth as the Witcher Explained: What Really Happened to Geralt

Why the Tracklist is Weirder Than You Remember

The album is split right down the middle: seven originals and seven covers. On paper, that sounds like a safe bet. In reality, the selection of covers tells you exactly where their heads were at. They weren't just playing rock and roll standards. They were obsessed with Motown and R&B.

Take "Money (That's What I Want)." Barrett Strong did the original, but the Beatles turned it into something feral. John Lennon’s vocal on that track sounds like he’s literally tearing his throat out. It’s not "nice" music. Then you have "Please Mister Postman" and "You Really Got a Hold on Me." They were obsessed with the Marvelettes and Smokey Robinson. They were white kids from a port city translating Black American soul music for a global audience, and they did it with a sincerity that most of their peers couldn't touch.

Then there’s George Harrison. This album gave us "Don't Bother Me," his first solo songwriting credit. George famously hated the song later, calling it "not a very good song" in his autobiography I, Me, Mine. But he’s wrong. It’s a moody, minor-key shift that signaled the "Quiet Beatle" had teeth. It broke the Lennon-McCartney monopoly early on, even if just by a crack.

The "All My Loving" Factor

If you want to talk about With The Beatles and its place in history, you have to talk about "All My Loving." Paul McCartney wrote this while he was shaving. Just a casual bit of genius before breakfast.

It’s arguably the first "perfect" pop song of the 1960s.

The rhythm guitar by John Lennon is insane. Go back and listen to it—those fast, triplet down-strokes. Most guitarists struggle to keep that pace for three minutes without their forearm seizing up. John did it effortlessly while singing backing vocals. It’s the engine of the song. When the Beatles performed this as their opener on The Ed Sullivan Show in February 1964, it was the shot heard 'round the world.

The Hidden Gem: It Won't Be Long

The album opens with "It Won't Be Long," and it’s a masterclass in the "Yeah, Yeah, Yeah" era. But look closer at the chords. They’re using augmented chords and weird transitions that shouldn't work in a pop song. They were bored with basic three-chord blues. They wanted more.

- "All I've Got to Do" – This is John doing his best Arthur Alexander impression. It’s smoky, jazz-influenced, and incredibly mature for a 22-year-old.

- "Not a Second Time" – Ian MacDonald, the famous musicologist who wrote Revolution in the Head, pointed out that this song uses "Aeolian cadences." John Lennon famously replied that he had no idea what those were, but he liked the sound.

- "Little Child" – Probably the weakest track on the record, but even here, the harmonica work gives it a gritty, busker feel that keeps the energy high.

- "I Wanna Be Your Man" – They gave this to the Rolling Stones first. The Stones got a hit out of it, and then the Beatles recorded their own version for Ringo to sing. It’s sloppy, it’s loud, and it’s basically a punk song ten years early.

The Production Gap

George Martin, their producer, was starting to realize he wasn't just recording a band; he was collaborating with a force of nature. On the first album, they basically played their live set. On With The Beatles, they started using the studio as an instrument.

They used double-tracking for the vocals—a technique where the singer records their part twice to create a thicker, more haunting sound. Today, every bedroom pop artist does this with a plugin. In 1963, it was a manual, painstaking process. It gave Lennon’s voice that "double" edge that became his signature.

There's also the matter of the stereo mix. If you listen to the original stereo version today, it’s a bit jarring. The vocals are pushed entirely into the right speaker and the instruments into the left. It was a product of the two-track recording technology of the time. For the "real" experience, most purists insist on the mono mix. It’s punchier. It hits you in the chest. It’s how the band intended it to be heard.

How it Changed the Industry

Before this album, the industry standard was "one hit single and twelve tracks of filler." The Beatles hated that. They wanted every song to be good enough to be a single. While they didn't put their actual UK hit singles (She Loves You and I Want to Hold Your Hand) on the album—a common practice in Britain back then to give fans more value for their money—the quality of the album tracks was staggeringly high.

In the US, Capitol Records made a mess of things. They took songs from this album, mixed them with singles, and released it as Meet The Beatles!. This created a massive rift in how American and British fans experienced the band. For the UK, With The Beatles was a cohesive artistic jump. For Americans, it was just part of the "British Invasion" explosion.

What People Often Miss

The most common misconception is that this album is "lightweight."

"Till There Was You" usually gets the blame for this. It’s a showtune from The Music Man. People think it’s just there to please the parents. But listen to George Harrison's nylon-string guitar solo. It’s sophisticated. It’s Latin-influenced. It shows a band that was listening to everything—Broadway, Jazz, Motown, Rockabilly—and folding it into a single identity.

Also, Ringo Starr’s drumming on this record is criminally underrated. On "Don't Bother Me," he’s playing a complicated, Latin-tinged beat that keeps the whole thing from becoming too mopey. Ringo was the "human metronome," but he had a swing that no one has ever quite been able to replicate.

Actionable Listening Guide

If you want to truly appreciate what happened during the making of this album, don't just stream it on your phone while doing the dishes.

- Find the Mono Mix: If you can, listen to the 2009 remastered mono version. The balance is much better, and the "power" of the band comes through more clearly than in the panned stereo version.

- Track the Influences: Listen to Smokey Robinson and the Miracles' "You Really Got a Hold on Me" and then immediately play the Beatles' version. Notice how they didn't just copy it; they added a certain Liverpool grit to the harmonies.

- Watch the Bournemouth Context: Look up the Robert Freeman photography sessions. Seeing the environment where they were staying helps explain the "darker" aesthetic of the record.

- Focus on the Rhythm Guitar: On your next listen, ignore the vocals. Just follow John Lennon's right hand on his Rickenbacker. It is a masterclass in rock rhythm technique that influenced everyone from The Who to the Ramones.

The legacy of With The Beatles isn't just that it sold a million copies before it was even released. It’s that it proved the Beatles weren't a fluke. They were a workhorse. They took the raw materials of American soul and reshaped it into something that felt universal. It remains a blueprint for how to handle fame: by working harder and getting weirder.

Check the liner notes of the 1963 release. You’ll see the band thanked their fans, but the music told the real story. They were already moving past the world that had created them. By the time the final chord of "Money" fades out, you realize you aren't listening to a "boy band." You’re listening to the beginning of the end of the old world.

The next step for any serious listener is to compare these tracks to the Live at the BBC recordings from the same era. You will hear the difference between their professional "radio" personas and the raw, aggressive energy they were bottling up in the studio for this specific album. It provides a bridge of understanding that no biography can match.