Ever stared at a spool of wire in a hardware store and felt that sudden wave of "I hope I don't burn my house down" anxiety? It’s a valid fear. Most people think electricity is like water in a pipe—get a bigger pipe, get more water. Simple. But electricity is a bit more temperamental. If you pick the wrong size from a wire gauge amp chart, you aren't just looking at a circuit that won't work. You’re looking at a potential fire hazard.

Wiring isn't just about making the light turn on. It's about heat management. When current flows through a conductor, it meets resistance. Resistance generates heat. If the wire is too thin (high gauge number) for the amount of current (amps) you're pushing through it, that wire becomes a heating element. Eventually, the insulation melts. That's how electrical fires start. Understanding the American Wire Gauge (AWG) system is the only thing standing between a successful project and a call to the fire department.

The Counterintuitive Logic of the Wire Gauge Amp Chart

Here is the first thing that trips everyone up: the numbers go backward. A 14-gauge wire is much thinner than a 10-gauge wire. It feels wrong, like trying to learn a language where "up" means "down." This stems from the way wire was historically manufactured. To make it thinner, you had to pull it through a series of increasingly smaller dies. Each "draw" made it thinner. So, a 20-gauge wire was pulled through 20 dies. It’s smaller because it’s been worked more.

📖 Related: How to Locate Address by Latitude and Longitude Without Losing Your Mind

When you look at a standard wire gauge amp chart, you’ll see specific pairings. For most residential work in North America, you're dealing with a handful of common sizes. A 14-gauge wire is generally rated for 15 amps. Move up to 12-gauge, and you’re at 20 amps. Jump to 10-gauge, and you can handle 30 amps. It sounds straightforward, but there are massive caveats that the charts on the back of the package don't tell you.

Why 80% is the Magic Number

You can't just run a 20-amp circuit at 20 amps all day. The National Electrical Code (NEC) has this "Continuous Load" rule. Basically, if a circuit is going to be running for more than three hours—think an air conditioner or a space heater—you should only load it to 80% of its capacity.

So, if you have a 20-amp circuit (using 12-gauge wire), you really only want to pull 16 amps continuously. Exceeding this doesn't necessarily trip the breaker immediately, but it keeps the wire perpetually hot. Over years, this heat cycles the wire, making the metal brittle and the insulation crumbly. It's a slow-motion disaster.

Factors That Throw Your Chart Out the Window

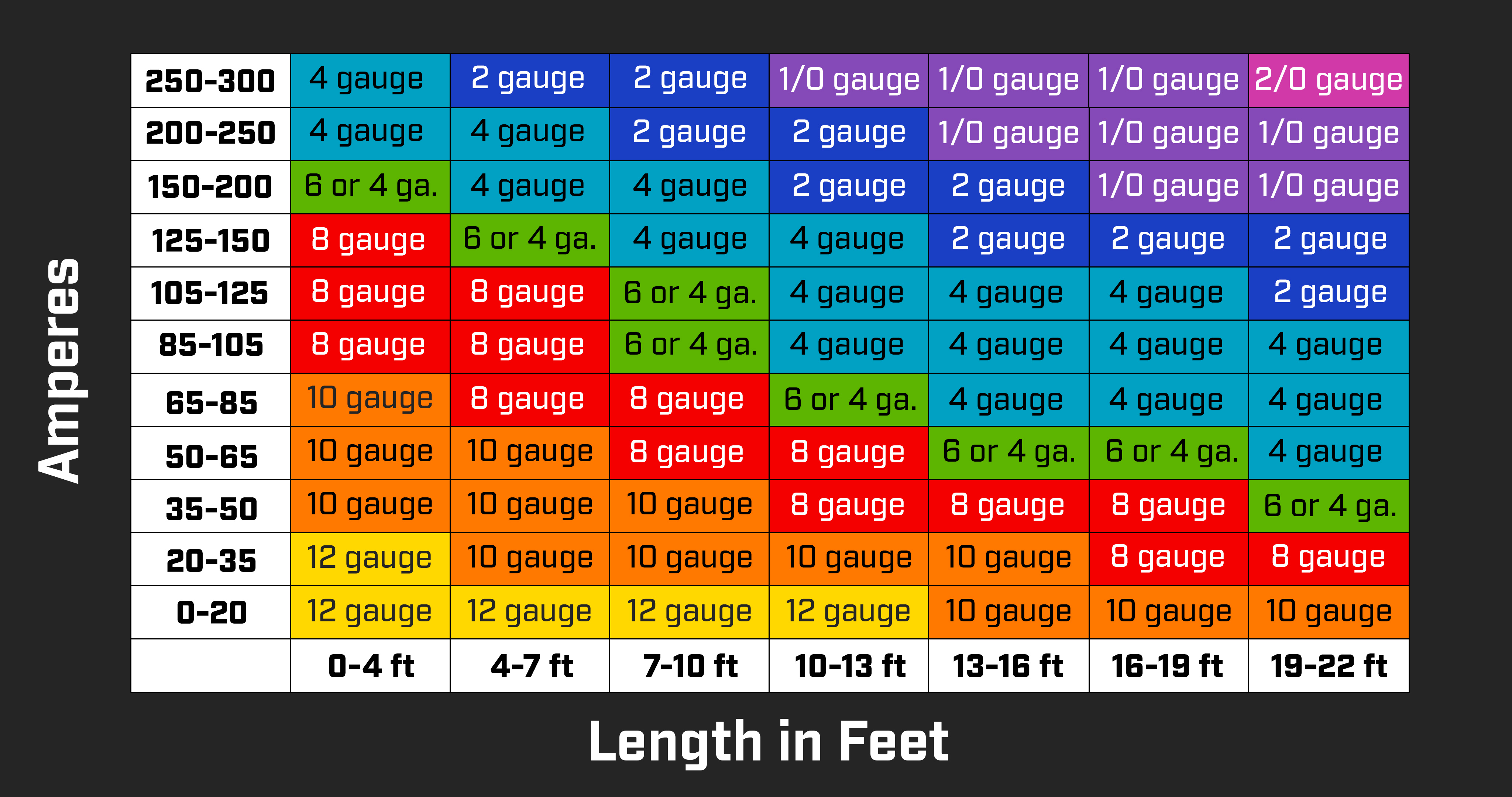

A wire gauge amp chart is a baseline. It assumes "perfect" conditions, usually room temperature and a short distance. But the real world is messy.

Take "Voltage Drop" for example. Electricity loses pressure as it travels. If you’re running a wire 100 feet to a backyard shed, a 14-gauge wire might still be rated for 15 amps, but by the time the power gets to the shed, the voltage has dropped so much that your power tools will bog down and overheat. To fix this, you "upsize" the wire. You might use 12-gauge or even 10-gauge for that same 15-amp load just to compensate for the distance.

Then there’s the "bundling" issue. If you cram ten wires through one hole in a wooden stud, they can't dissipate heat. They cook each other. Professional electricians call this "derating." If you have too many conductors in one conduit or hole, you actually have to lower the ampacity you’re allowed to run through them. It’s a nuance that many DIYers—and even some lazy pros—completely ignore.

Temperature Ratings and Insulation Types

Have you noticed the letters printed on the side of a wire? THHN, ROMEX (NM-B), XHHW. These aren't just alphabet soup. They tell you what the insulation can handle.

Most modern residential wire (NM-B) is rated for 90°C, but the NEC often requires you to use the 60°C or 75°C column on a wire gauge amp chart for safety. Why? Because the terminals on your outlets and breakers are usually only rated for 60°C or 75°C. If the wire gets hotter than the connection point can handle, the connection fails. A chain is only as strong as its weakest link, and in your wall, that link is often the screw terminal on a $0.75 outlet.

Real-World Applications: What Goes Where?

Let’s get practical. If you're wiring a house, you aren't just picking gauges at random. There is a standard rhythm to it.

🔗 Read more: Free vending machine code: How the "hacks" actually work and why most of them are fake

- 14-Gauge (15 Amps): This is for your basic lighting circuits and some bedroom outlets. It’s easy to work with because it’s thin and flexible.

- 12-Gauge (20 Amps): The gold standard for kitchen outlets, bathrooms, and laundry rooms. These areas have high-draw appliances like blenders, hair dryers, and toasters.

- 10-Gauge (30 Amps): Usually reserved for dedicated lines. Think electric clothes dryers or water heaters. It’s stiff. Working with it feels like trying to bend a coat hanger.

- 8-Gauge and 6-Gauge (40-55 Amps): Now we're talking about electric ranges or EV chargers.

Tesla chargers are a great example of where people mess up. A Wall Connector can pull 48 amps. If you look at a basic wire gauge amp chart, you might think 6-gauge is fine. But since it’s a continuous load, you actually need to size it for 60 amps of capacity. This usually means 6-gauge THHN in conduit or 4-gauge if you’re using Romex. If you use the wrong one, the wall gets warm. Warm walls are bad.

Copper vs. Aluminum: The Great Debate

In the 1960s and 70s, copper prices spiked, so builders started using aluminum wiring for everything. It was a nightmare. Aluminum expands and contracts differently than copper when it gets hot. This caused connections to loosen, sparks to fly, and houses to burn.

Today, aluminum is perfectly safe for large-scale "service entrance" wires—the big fat ones coming from the utility pole to your house. But for the small stuff inside your walls? Stick to copper. If you do use aluminum for a sub-panel, remember that you almost always have to go up two sizes. An 8-gauge copper wire is roughly equivalent to a 6-gauge aluminum wire in terms of ampacity.

The Myth of the "Over-Wired" House

Is there such a thing as wire that's too thick? Technically, no. Using 12-gauge wire on a 15-amp circuit is actually "safer" because it has less resistance and stays cooler. Some high-end builders do this as a selling point. However, it’s a pain in the neck to install. Thicker wire takes up more room in the electrical box. It’s harder to fold the wires back and screw the outlet in place. If you've ever tried to shove three 12-gauge wires into a small plastic box, you know the struggle. It’s a workout for your thumbs.

📖 Related: Apple Watch Series 10 46mm: Why the Biggest Screen Isn't Just for Big Wrists

How to Read a Wire Gauge Amp Chart Like a Pro

When you find a chart online, don't just look at the first column. Look for the headers. You’ll usually see columns for different temperatures (60°C, 75°C, 90°C).

- Identify your wire material: Is it copper or aluminum?

- Check your insulation: Look for the letters (like THHN) on the jacket.

- Find the lowest rated component: Even if your wire is rated for 90°C, if your breaker says 75°C, you use the 75°C column.

- Factor in distance: If the run is over 50 feet, consider bumping up one size.

I once saw a guy try to run a whole-house AC unit on 12-gauge wire because "that's what he had in the garage." The wire didn't melt instantly. It took about twenty minutes. By the time the breaker tripped, the smell of burnt plastic had permeated the entire basement. He was lucky he was standing there. Most people aren't.

Moving Beyond the Chart

A wire gauge amp chart is a tool, not a rulebook. The rulebook is the NEC (or your local equivalent). These codes change every few years as we learn more about electrical failures. For instance, the 2023 NEC updates have stricter rules about GFCI and AFCI protection, which doesn't change the wire size but definitely changes how you install it.

If you’re unsure, honestly, just call an electrician. Or at the very least, buy a copy of "Wiring Simplified" by Richter and Schwan. It’s the bible for this stuff.

Next Steps for Your Project:

- Calculate your total load: Add up the wattage of everything that will be plugged into that circuit. Divide total watts by volts (usually 120) to get your amps.

- Apply the 80% rule: If your load is 12 amps, a 15-amp circuit is fine. If it's 13 or 14, jump to a 20-amp circuit.

- Check your distance: Measure the literal path the wire takes, not just the straight-line distance.

- Inspect your terminals: Ensure your outlets and switches are rated for the wire size you've chosen. Putting 10-gauge wire on a standard 15-amp outlet is nearly impossible without special connectors.