Chicago in 1946 was a city on edge. The war was over, but something felt deeply wrong on the North Side. Women were being found dead in their bathtubs, and then a six-year-old girl named Suzanne Degnan vanished from her bedroom in the middle of the night.

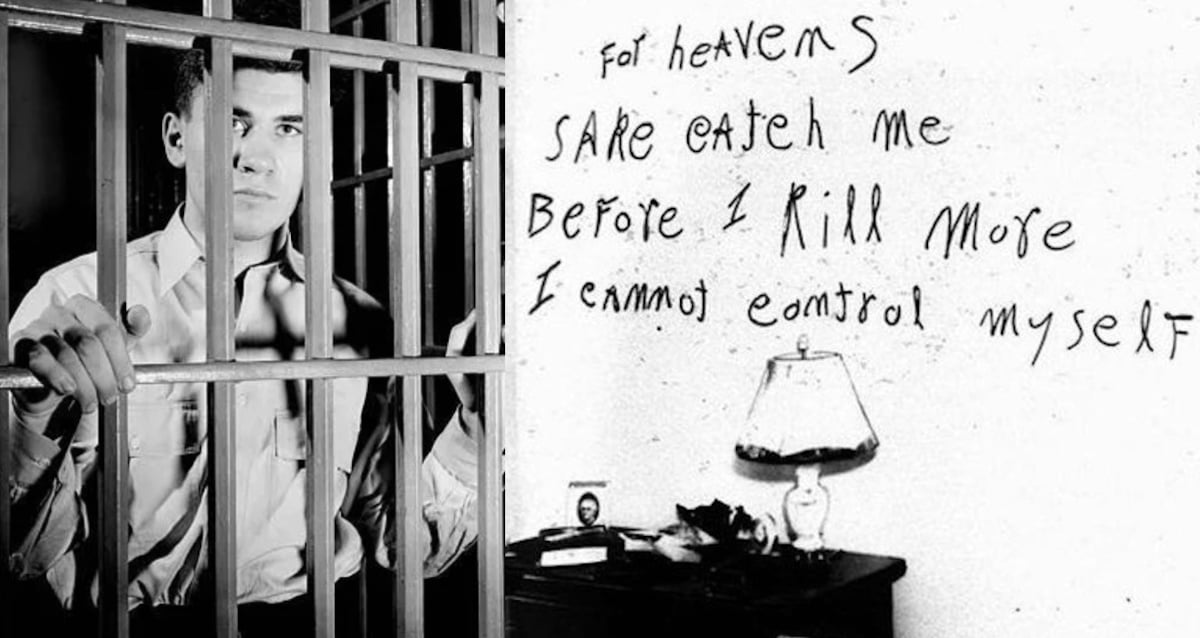

By the time the police caught a scrawny 17-year-old University of Chicago student named William Heirens, the public was screaming for blood. He became the Lipstick Killer in the headlines before he ever stepped foot in a courtroom. Honestly, if you look at the newspapers from that era, the trial was over before it started. But if you dig into the actual files, the "slam dunk" case against Heirens starts to look incredibly shaky.

The Crimes That Terrified a City

The moniker didn't come from nowhere. It started with the murder of Frances Brown in December 1945. She was found in her apartment, shot and stabbed, but the detail that paralyzed the city was the message scrawled on the wall in her own lipstick: “For heavens sake catch me before I kill more I cannot control myself.”

It was a headline writer's dream and a citizen's nightmare.

Before Frances, there was Josephine Ross in June 1945. She’d been stabbed repeatedly in her apartment, her head wrapped in a dress. Then came the breaking point: Suzanne Degnan. On January 7, 1946, a ladder was found outside the Degnan window. A ransom note demanded $20,000. Later that day, the girl's dismembered remains were found in various sewers and catch basins around the neighborhood.

🔗 Read more: No Kings Day 2025: What Most People Get Wrong

The police were under immense pressure. They had no real leads, and the "Lipstick Killer" was becoming a local boogeyman. Then they caught Heirens.

The Arrest and the "Truth Serum"

Heirens wasn't caught for murder. He was caught for a botched burglary. When he tried to flee, an off-duty cop famously dropped a flower pot on his head, knocking him cold. That’s how the investigation began—with a teenager suffering from a severe concussion.

What happened next is, quite frankly, horrifying by modern legal standards.

- Sodium Pentothal: While hospitalized, Heirens was injected with "truth serum" without his consent or his parents' knowledge.

- The Interrogation: He was questioned for six days without a lawyer. He claimed he was beaten, burned with ether on his genitals, and denied food.

- The Confession: He eventually "confessed," but the details were a mess. He often just repeated what he had read in the Chicago Tribune, which was leaking supposedly "unimpeachable" details from the police.

Basically, the kid was broken. He later said he confessed just to avoid the electric chair. "I confessed to live," he told reporters years later. He spent 65 years in prison—becoming the longest-serving inmate in Illinois history—and he spent almost every one of those years trying to take that confession back.

💡 You might also like: NIES: What Most People Get Wrong About the National Institute for Environmental Studies

Why the Evidence Doesn't Hold Up

If you talk to legal experts today, like those from the Northwestern University Center on Wrongful Convictions, they’ll tell you the physical evidence was a joke.

Take the fingerprints. The police claimed they found Heirens' print on the Degnan ransom note and in Frances Brown's apartment. But later re-examinations suggested those prints might have been "constructed" or planted. Even more damning? The handwriting. A handwriting expert, Herbert J. Walker, initially said Heirens wrote the lipstick message. Later, he recanted, admitting there were "a great many dissimilarities" between Heirens' writing and the scrawl on the wall.

Then there’s the "surgical kit." The police found two surgical kits in Heirens' possession and claimed he used them to dismember Suzanne Degnan. Heirens, a model airplane enthusiast, said he used the tools for his hobby. More importantly, the coroner at the time said the dismemberment was so expert it had to be a "meat cutter" or someone with professional anatomical knowledge. Heirens was a 17-year-old math student.

The Other Suspect Everyone Ignored

There was another guy. Russell Richard Thomas. He was a former nurse—someone with medical knowledge. He actually confessed to the Degnan murder from a jail cell in Phoenix right around the time Heirens was caught. But the Chicago police, already deep into the Heirens narrative, basically brushed him off. Thomas had a history of violence and kidnapping, yet he was never seriously pursued as the Lipstick Killer once Heirens was in the hot seat.

📖 Related: Middle East Ceasefire: What Everyone Is Actually Getting Wrong

A Legacy of Doubt

William Heirens died in 2012 at the age of 83. He never got out.

To the Degnan family, he remained a monster. Suzanne's sister, Betty Finn, fought his parole for decades, convinced he was the one who destroyed her family. You can’t blame her for that. The crimes were real and they were evil.

But for those who value the integrity of the law, the case is a stain. It was a perfect storm of a panicked public, a sensationalist press, and a police department willing to use "junk science" and coercion to get a win.

Actionable Takeaways for True Crime Followers

If you’re researching the William Heirens lipstick killer case or similar historical crimes, keep these things in mind to separate legend from fact:

- Check the "Truth Serum" Validity: Remember that sodium pentothal is no longer admissible or considered reliable; it makes subjects highly suggestible, meaning they often "confess" to whatever the interrogator wants to hear.

- Verify Forensic Standards: Fingerprint and handwriting analysis in the 1940s was nowhere near the digital precision we have today. "Matches" were often subjective opinions.

- Look for Coerced Confession Patterns: Study how the Chicago Tribune's reporting influenced Heirens' testimony. When a suspect's story only matches what’s in the news, it’s a huge red flag for a false confession.

- Examine the Political Climate: High-profile arrests in the 40s often coincided with elections or police scandals. Context matters.

The story of the Lipstick Killer isn't just about a series of murders. It’s a cautionary tale about what happens when a city decides it needs a villain more than it needs the truth.

To better understand the evolution of forensic science and how it has changed the investigation of cases like this, you can look into the history of the Northwestern Center on Wrongful Convictions or the Innocence Project. These organizations provide deep insights into how historical evidence is being re-evaluated today.