Ever stood in a field at dusk and felt like something was watching you from the tree line? Not something scary, exactly. Just something... old. For folks in certain parts of the Ozarks and the Appalachian foothills, that feeling has a name. It’s tied to a story that refuses to die, a tale of a stallion that isn't quite meat and bone anymore. We’re talking about Wildfire: The Legend of the Cherokee Ghost Horse, a narrative that has drifted through oral traditions, campfire circles, and even 1970s pop culture, picking up new layers of meaning with every generation.

It’s a weirdly persistent myth. You might know the name from the Michael Martin Murphey song—that 1975 hit that somehow manages to make everyone feel nostalgic for a horse they never owned and a blizzard they never lived through. But the song didn’t just pop out of thin air. It tapped into a vein of folklore that's deeply rooted in the tragedy of the Trail of Tears and the spiritual connection between the Cherokee people and the animals they left behind—or lost—along the way.

Some people call it a ghost story. Others see it as a metaphor for lost sovereignty. Honestly, it’s probably a bit of both.

The Roots of the Ghost Horse Narrative

To get why people still talk about the ghost horse, you have to look at the historical trauma of the 1830s. When the Cherokee were forced from their ancestral lands in the Southeast to "Indian Territory" (now Oklahoma), they didn't just lose their homes. They lost their livestock, their companions, and their way of life. Thousands died. The "Trail of Tears" wasn't just a human tragedy; it was an ecological and cultural uprooting.

In many versions of the Wildfire: The Legend of the Cherokee Ghost Horse story, the horse represents the spirit of what was lost. Legend says a young woman—often identified as Cherokee—owned a pony or a stallion of incredible beauty and speed. During a devastating winter storm, the horse broke free. Some say it was trying to lead the people to safety; others say it was fleeing the encroaching cold. The girl went out to find him, and neither were ever seen alive again.

But death isn't the end in Cherokee cosmology. Spirits linger. The horse, now a shimmering, spectral figure, is said to appear right before major environmental shifts. If you see a white horse running through a blizzard where no horse should be, you’re looking at Wildfire.

Why We Still Sing About It

Michael Martin Murphey’s song "Wildfire" is basically responsible for cementing this legend into the American consciousness. It’s a haunting track. It’s got that piano intro that feels like falling snow. Murphey has often spoken about how the song came to him in a dream, but he also acknowledges the influence of the stories he heard growing up in Texas. He once mentioned in an interview that the concept of the "ghost horse" was something he’d encountered in various forms of Southwestern and Native American lore.

✨ Don't miss: The Long Haired Russian Cat Explained: Why the Siberian is Basically a Living Legend

The song tells a story of a pony named Wildfire and a girl who dies calling his name in a "killing frost." It’s bleak. It’s beautiful. And it totally reframed the folk legend for a modern, mainstream audience.

But there’s a gap between the pop song and the actual indigenous roots. Native American scholars, like those who contribute to the American Indian Quarterly, often point out how these legends get "romanticized" by Western creators. While the song is a masterpiece of storytelling, the original Cherokee context is much more about the land’s memory. The ghost horse isn't just a sad pet; it’s a guardian of the landscape. It’s a reminder that the bond between the people and the Earth wasn’t broken by forced removal.

Breaking Down the "Ghost Horse" Sightings

Believe it or not, people still claim to see this thing. Paranormal researchers and folklorists who track "phantom animals" often receive reports of a glowing white stallion in the mountains of North Carolina and the plains of Oklahoma.

Are they seeing a literal ghost? Probably not.

Most "sightings" can be chalked up to:

- Atmospheric phenomena: Low-lying mist in a valley can look remarkably like a moving animal if the wind catches it right.

- The "Spirit Horse" Archetype: Humans are hardwired to see patterns. The horse is a symbol of freedom and power. When we are in nature and feel a sense of awe or dread, our brains often fill in the blanks with symbols we know.

- Escaped Livestock: There are still wild horse populations in the U.S. A palomino or a grey horse seen through a thicket in bad lighting looks pretty spectral.

But here is the thing: the "truth" of the sighting matters less than the "truth" of the feeling. The Wildfire: The Legend of the Cherokee Ghost Horse persists because it speaks to a universal human experience—the grief of losing something we can't replace and the hope that it’s still out there, running free.

🔗 Read more: Why Every Mom and Daughter Photo You Take Actually Matters

The Cultural Impact of the Wildfire Myth

The legend has leaked into all sorts of places. You see it in literature, in the way "spirit animals" are depicted in fantasy novels, and in the persistent trope of the "white horse" as a harbinger of change. It’s a cross-cultural phenomenon, really.

Think about the "Pacing White Stallion" of the West, a legend documented by J. Frank Dobie. That horse was said to be so fast and so wild that no man could ever catch it, eventually jumping off a cliff to its death rather than being corralled. There's a clear overlap here. The Cherokee version adds a layer of spiritual depth because it’s tied to a specific people’s history and their endurance through suffering.

Is There Any Scientific Basis for These Legends?

Science doesn't usually deal in ghosts, but it does deal in ancestral memory and oral history.

Researchers in the field of geomythology study how ancient myths often preserve records of actual geological events. While the Ghost Horse isn't a volcano or an earthquake, the stories of "killing frosts" and "darkened suns" in these legends often correlate with the "Year Without a Summer" in 1816 or the extreme weather events of the early 19th century. These were real, documented climate disasters. For the Cherokee, who were already under immense political pressure, a massive crop-killing frost would have felt apocalyptic.

When you live through a trauma that big, you don't just write a history book. You tell a story. You create a symbol—a horse named Wildfire—that carries the weight of that winter so your grandkids will remember how hard it was.

Misconceptions About the Legend

People get a lot of stuff wrong about this story. For one, it’s not a "spooky" ghost story in the traditional sense. It’s not meant to scare kids into staying in bed. It’s more of a melancholy legend.

💡 You might also like: Sport watch water resist explained: why 50 meters doesn't mean you can dive

Another big misconception? That it’s a "universal" Native American myth. It isn't. It is specifically tied to the nations that were affected by the Southeast removals. You won't find the same "Wildfire" story in Navajo or Haida culture. Their horse stories are completely different because their relationship with the animal and the geography is different.

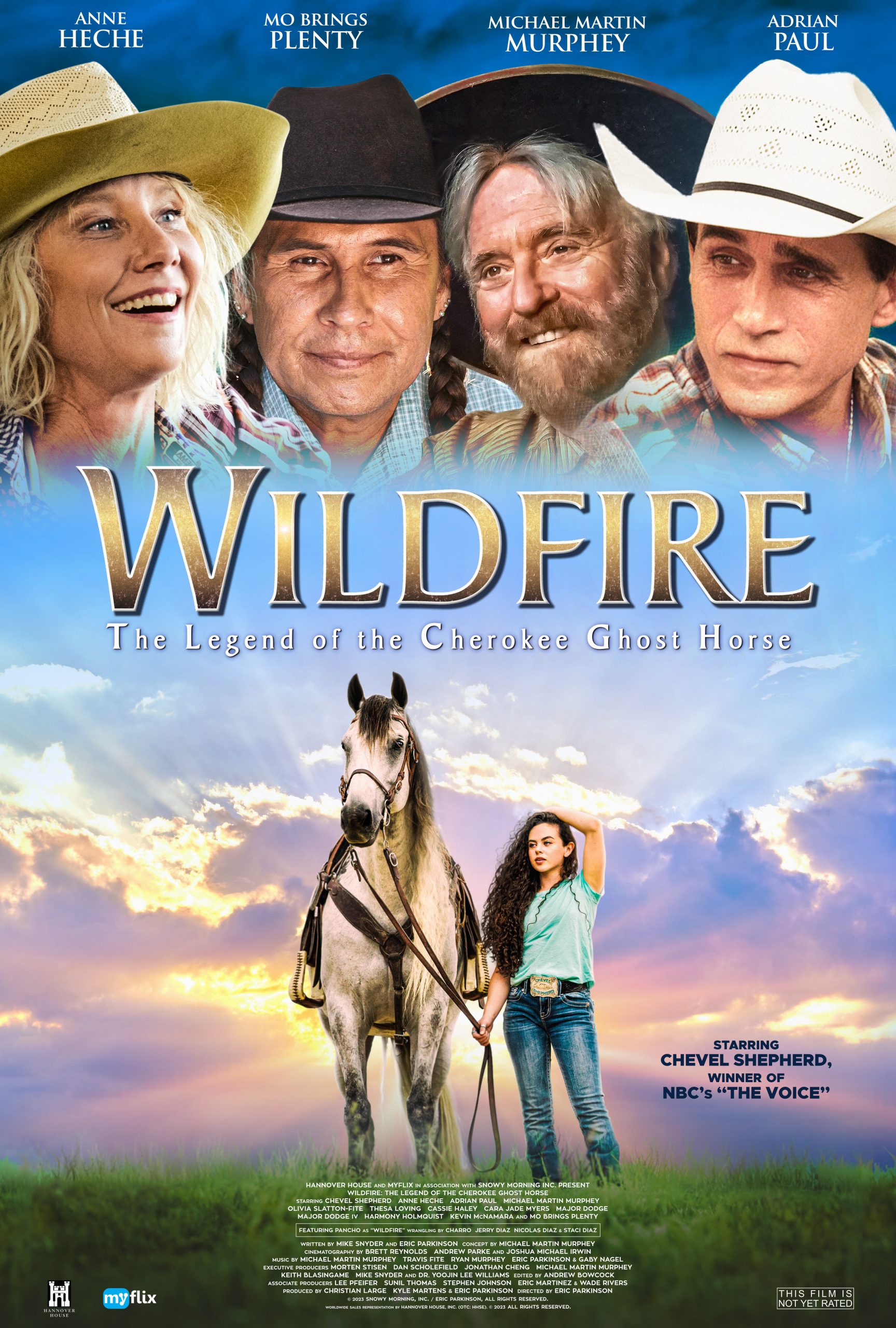

Also, don't confuse the legend with the "Wildfire" TV show from the mid-2000s or various horse-racing movies. Those might borrow the name for its evocative power, but they usually strip away the Cherokee roots entirely.

Living with the Legend Today

So, what do we do with a story like Wildfire: The Legend of the Cherokee Ghost Horse in 2026?

We use it as a bridge. It’s a way to talk about the history of the Trail of Tears without just reciting dates and numbers. It’s a way to acknowledge the emotional reality of that time.

If you’re ever traveling through the Great Smoky Mountains or the hills of eastern Oklahoma, keep an eye on the ridges during a storm. You probably won't see a glowing horse. But you might feel the weight of the history that created the story. That’s the real haunting.

Actionable Ways to Explore the History

If you want to move beyond the folklore and understand the real context of this legend, there are better ways than just scrolling through "creepypasta" forums.

- Visit the Trail of Tears National Historic Trail. There are sites across nine states. Standing on the actual ground where these events happened changes your perspective on the folklore.

- Support Indigenous Storytellers. Look for books by Cherokee authors like Kelli Jo Ford or Brandon Hobson. They offer a contemporary and authentic look at how history and spirit continue to influence the present.

- Listen to the Music with New Ears. Go back and listen to Michael Martin Murphey’s "Wildfire," but keep the historical context in mind. Notice how the lyrics focus on the "break in the hoot-owl lane" and the "killing frost." It’s a weather report wrapped in a tragedy.

- Research the "Spirit Horse" in Art. Look at the work of Native American artists who use equine imagery. You'll see that the horse is often a symbol of resilience and the continuation of life after a period of intense suffering.

The legend of Wildfire isn't just a campfire story. It’s a piece of living history that has survived through song, memory, and the enduring power of the landscape. Whether you believe in ghosts or not, the story serves as a testament to the things we refuse to let go of. It’s about the horses we lost, the lands we left, and the spirits that keep on running, long after the frost has cleared.