You know that feeling. You wake up on a Tuesday morning, try to roll out of bed, and your quads scream. Yesterday’s leg day seemed fine at the time, but now even sitting on the toilet feels like a feat of Olympic proportions. It's frustrating. It's painful. Honestly, it’s just plain annoying when you're trying to stay consistent with a routine.

Most people call it "the burn," but the technical term is Delayed Onset Muscle Soreness, or DOMS. Understanding what causes soreness after exercise isn't just about satisfying your curiosity; it’s about knowing the difference between a productive workout and a literal injury. We’ve been told for decades that lactic acid is the villain here. That’s actually wrong. It’s a myth that won’t die, even though exercise physiologists debunked it years ago. Lactic acid clears out of your system within an hour or two of finishing your sprints or squats. It doesn't hang around for two days just to make your life miserable.

So, if it’s not the acid, what is it?

The Microscopic Reality of What Causes Soreness After Exercise

When you push your body—especially with movements it isn’t used to—you’re creating tiny, microscopic tears in your muscle fibers and the connective tissue surrounding them. Think of it like a rope being pulled just a little too hard. It doesn't snap, but some of the individual threads start to fray.

This sounds scary. It’s not.

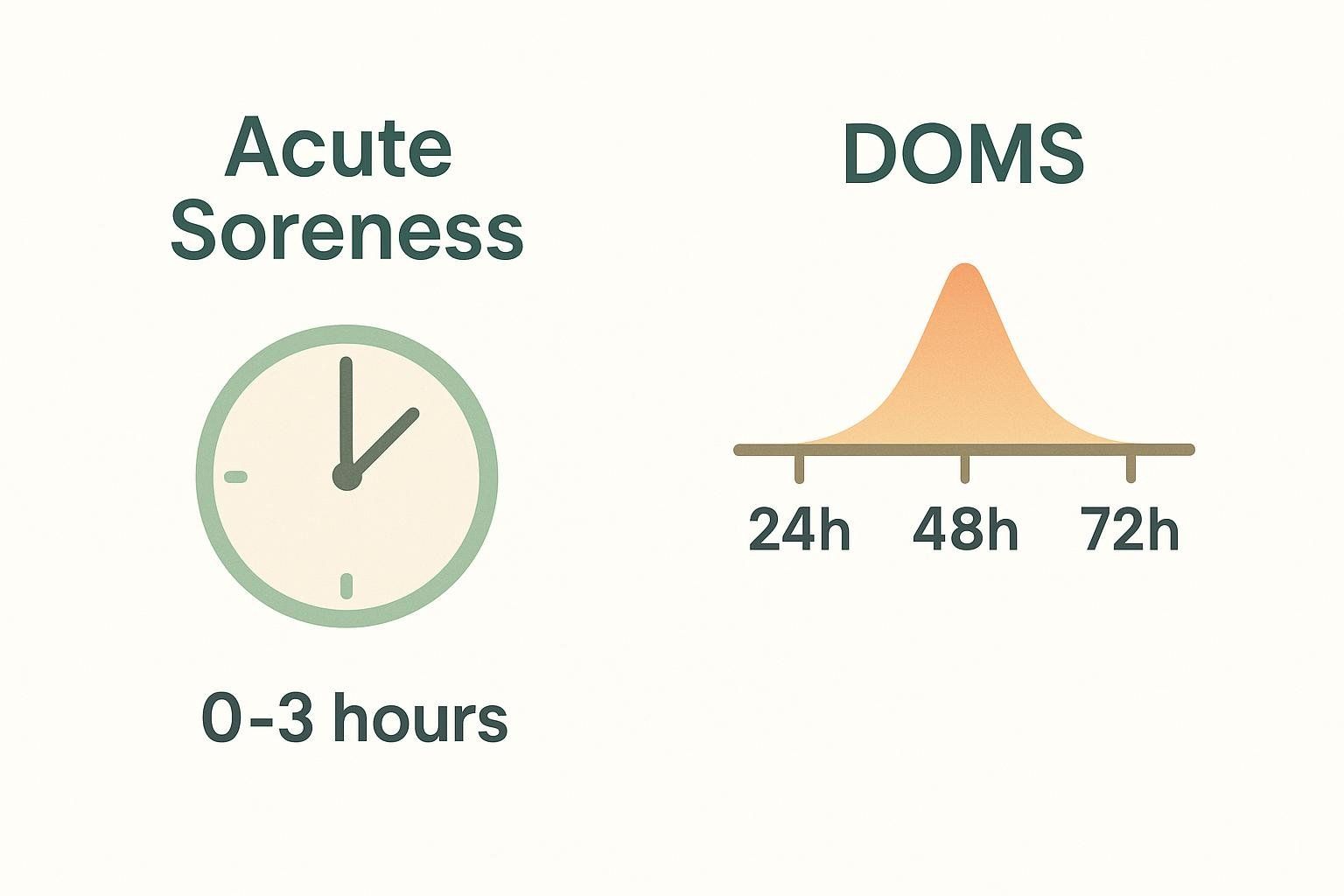

These micro-tears are the fundamental catalyst for muscle growth. Your body senses the damage and triggers an inflammatory response. This is where the magic (and the misery) happens. White blood cells, specifically neutrophils and macrophages, rush to the site of the "injury" to clean up the debris and start the repair process. This influx of fluid and chemicals increases pressure on the nerve endings in your muscle tissue. That’s why you don’t feel it immediately. The inflammatory cascade takes time to peak, usually hitting its stride between 24 and 72 hours after the workout.

It’s All About the Eccentric

Not all exercises are created equal when it comes to DOMS. If you want to know what causes soreness after exercise most aggressively, look at the "eccentric" phase of a movement. This is the lengthening part of the muscle contraction.

Imagine a bicep curl. Lifting the weight up is the concentric phase. Lowering it back down slowly? That’s the eccentric phase. Running downhill is a massive eccentric load on your quads because they are lengthening while trying to break your fall with every step. Research, including classic studies published in The Journal of Physiology, has consistently shown that eccentric exercise causes significantly more structural damage and subsequent soreness than isometric or concentric-only movements.

💡 You might also like: That Weird Feeling in Knee No Pain: What Your Body Is Actually Trying to Tell You

If you’ve ever wondered why your calves are shredded after a hike that was mostly downhill, there's your answer. Your muscles were essentially acting as brakes while being stretched out.

The Role of Fascia and Fluid

We talk a lot about muscles, but the fascia—the silver, spiderweb-like connective tissue that wraps around every muscle—plays a huge role in the "stiff" feeling you get. When you train hard, that fascia can become slightly dehydrated or "sticky." It loses its ability to glide smoothly over the muscle belly. This contributes to that sensation of being "locked up."

There's also the element of calcium. During intense exercise, calcium can leak out of the sarcoplasmic reticulum (a part of your muscle cells) and accumulate. This high concentration of calcium can further damage the cell membrane and trigger more inflammation. It’s a complex chemical soup happening under your skin.

Why Some People Hurt More Than Others

Genetics are a factor. Some people are "low responders" to exercise-induced muscle damage, while others feel like they've been hit by a truck after a light jog. This often comes down to the ACTN3 gene, which influences how muscle fibers handle stress and repair.

Conditioning is the bigger variable, though. There is a phenomenon called the Repeated Bout Effect (RBE). Basically, your body is incredibly smart. Once you perform a specific type of exercise that causes soreness, your muscles adapt to protect themselves from that specific stressor in the future. The next time you do that same workout, the damage will be significantly less. This is why the first week of a new gym program is hell, but the third week feels manageable. You haven't necessarily gotten "stronger" yet in terms of muscle size, but your nervous system and muscle membranes have learned how to brace for the impact.

Distinguishing "Good" Soreness from "Bad" Pain

This is where things get tricky. We’ve been conditioned to think "no pain, no gain," which is a dangerous half-truth.

DOMS (The Good Stuff):

📖 Related: Does Birth Control Pill Expire? What You Need to Know Before Taking an Old Pack

- Starts 12–24 hours later.

- Feels like a dull ache or tightness.

- The pain is symmetrical (both legs hurt equally).

- It improves slightly once you start moving and get the blood flowing.

Injury (The Bad Stuff):

- Starts during the workout or immediately after.

- Feels sharp, stabbing, or localized to one specific spot.

- Causes swelling that looks "angry" or bruised.

- Prevents you from performing basic movements (like a limp that won't go away).

If you’re feeling a sharp pain in your knee or a "pop" in your shoulder, that isn't what causes soreness after exercise—that’s structural damage to a joint or tendon. Tendons have very poor blood supply compared to muscles, so they don’t "recover" with a little rest and a protein shake. They need professional attention.

Myths That Need to Die

We already touched on the lactic acid thing, but let’s talk about stretching. Many people swear that stretching after a workout prevents DOMS.

The data says otherwise.

A massive Cochrane review that looked at twelve different studies concluded that stretching before or after exercise does not produce a clinically important reduction in delayed-onset muscle soreness in healthy adults. It might feel good in the moment because it stimulates the nervous system, but it doesn't actually stop the micro-tears from happening or speed up the inflammatory repair process. In fact, if you stretch too aggressively when your muscles are already damaged, you might actually be causing further micro-trauma.

How to Actually Facilitate Recovery

If you can’t stretch it away and you can’t wish it away, what can you do?

The most effective tool is Active Recovery.

👉 See also: X Ray on Hand: What Your Doctor is Actually Looking For

Sitting on the couch only makes the stiffness worse because blood isn't circulating through the damaged tissue to clear out metabolic waste. A light walk, easy swimming, or a very low-intensity bike ride increases blood flow without adding more structural damage. This "flushing" effect is the gold standard for managing what causes soreness after exercise.

Nutrition is the second pillar. You need protein to repair the structural damage (the tears) and carbohydrates to replenish the glycogen stores you burned through. There is also some evidence that omega-3 fatty acids and certain antioxidants, like those found in tart cherry juice, can dampen the inflammatory response slightly. However, you don't want to shut down inflammation entirely. Inflammation is the signal that tells your body to grow back stronger. If you take high doses of Ibuprofen after every workout, you might actually be blunting your long-term muscle gains.

The Psychology of the Ache

There's a weird psychological satisfaction in being sore. For many, it's a badge of honor. It’s proof that you "did the work."

But be careful. Being perpetually sore is a sign of overtraining. If you are constantly in a state of DOMS, your body never actually finishes the repair process. You’re just digging a deeper hole. Growth doesn't happen in the gym; it happens while you’re sleeping. If you aren't seeing progress in your strength or endurance despite being "sore all the time," you aren't training hard—you're just recovered poorly.

Actionable Steps for Your Next Workout

Don't let the fear of soreness stop you. Use these specific strategies to manage the load.

- Introduce new movements gradually. If you’re starting a new program, don't go to failure on the first day. Give your body a chance to trigger the Repeated Bout Effect without overwhelming the system.

- Focus on sleep. Human Growth Hormone (HGH) is primarily released during deep sleep. If you get 5 hours of sleep after a heavy leg day, you’re going to hurt way more than if you got 8 hours.

- Hydrate, but with electrolytes. Dehydration makes the sensation of muscle pain much more acute. Your nerves need sodium, potassium, and magnesium to fire correctly and to manage the fluid shifts in your muscle cells.

- Try Contrast Water Therapy. If you're really hurting, alternating between a hot shower and a cold plunge (or just a cold spray) can help stimulate vasodilation and vasoconstriction, acting like a pump for your circulatory system.

- Listen to your "Morning Readiness." If your resting heart rate is 10 beats higher than usual and your legs feel like lead, take a rest day or do a "mobility only" session.

Understanding what causes soreness after exercise allows you to stop panicking when you feel stiff. It’s just your body’s way of remodeling itself into a more resilient version. Respect the process, feed the repair, and move enough to keep the blood flowing. The pain is temporary, but the physiological adaptations are what stay with you.

Focus on the trend, not the individual day. If you’re consistently moving better and feeling stronger over a month, the occasional "can't-walk-down-the-stairs" Tuesday is just a part of the journey. Keep your protein high, your sleep consistent, and your ego in check when trying new exercises. That’s how you win the long game.