You've probably been there. You're staring at your phone, looking at a weather forecast radar map that shows a giant, terrifying blob of red heading straight for your backyard. You cancel the grill out. You bring the dog in. Then? Nothing. Just a light drizzle or maybe even a bit of sun peeking through the clouds. It feels like the app lied to you, but usually, it’s just a misunderstanding of what that colorful pixels actually represent.

The tech is incredible. Truly.

But it’s also limited by physics. Most people think they're looking at a live video of rain. They aren't. They're looking at a computer's best guess based on pulses of energy reflecting off objects in the sky. Sometimes those objects are rain. Sometimes they're biological.

The Doppler Effect and Why Colors Lie

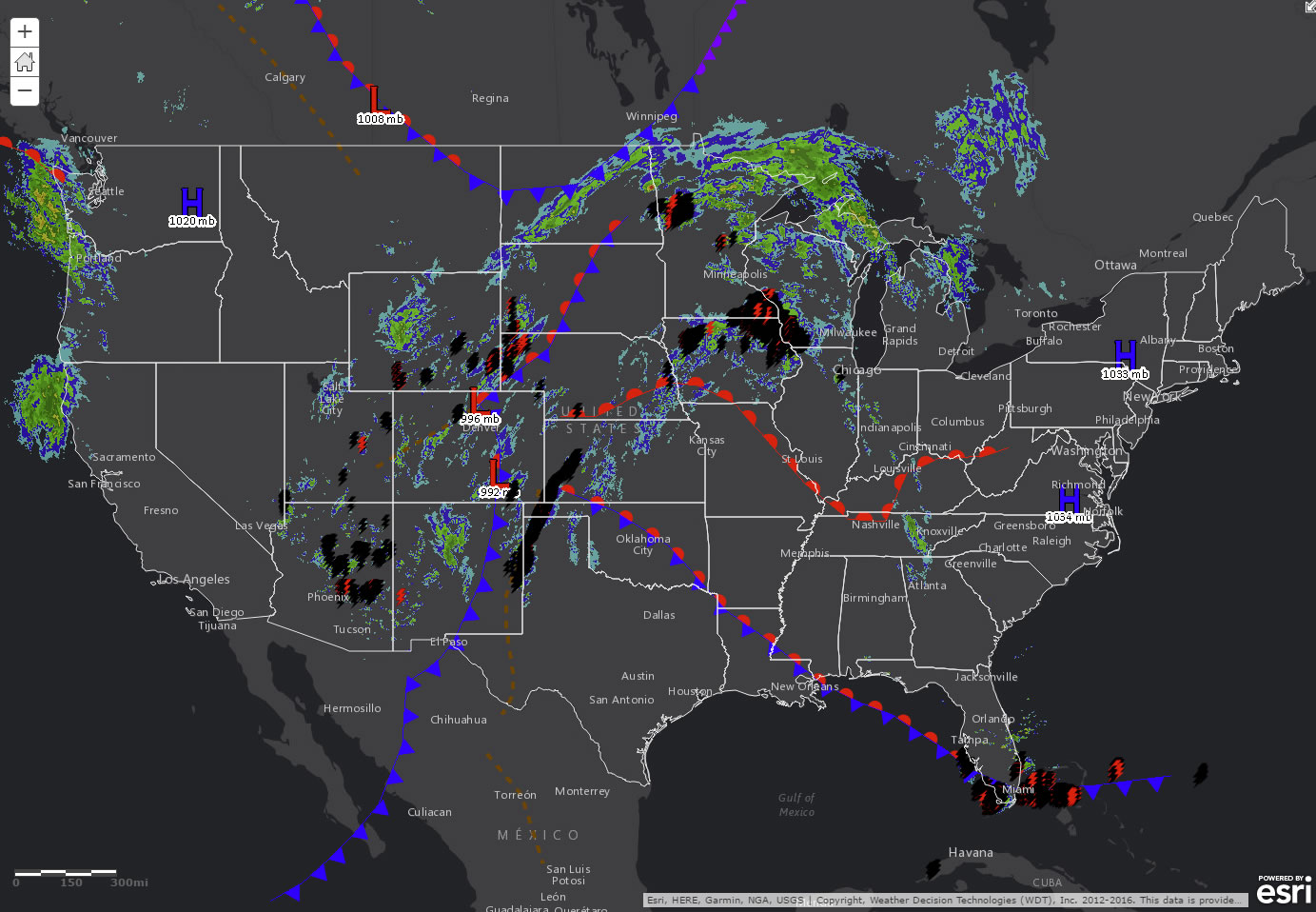

Radar stands for Radio Detection and Ranging. It’s old tech that has been polished to a mirror finish by modern computing. The National Weather Service (NWS) uses the WSR-88D system, better known as NEXRAD. There are 159 of these stations across the United States. Each one sends out a burst of radio waves. When those waves hit something—a raindrop, a snowflake, or even a swarm of beetles—they bounce back.

The "Doppler" part is what matters for safety. By measuring how the frequency of that returned signal changes, the radar can tell if the wind is moving toward or away from the station. This is how we spot rotation in clouds before a tornado even touches the ground. It's the difference between having five minutes to hide and having twenty.

But here is the kicker: reflectivity.

When you see bright red on a weather forecast radar map, you think "heavy rain." Usually, that's true. But the radar is actually measuring "DBZ" (decibels of Z). A high DBZ just means something big or dense is reflecting a lot of energy. Wet hail looks like massive rain to a radar. Big, wet snowflakes can look like a torrential downpour because they have a large surface area.

Ever see a weird "ghost" circle around a radar station? That's often ground clutter or "anomalous propagation." Basically, the radar beam gets bent toward the earth and hits trees or buildings. The computer thinks it's a storm. You think you need an umbrella. You don't.

Understanding the "Cone of Silence"

Every radar has a blind spot. Because the dish tilts upward to scan different slices of the atmosphere, it can't see what's directly on top of it. This is the "cone of silence." If a storm is sitting right on the station, the radar might show a hole in the middle of the rain.

Also, the further away you are from the station, the less accurate the map becomes. Why? Because the Earth is curved. A radar beam travels in a straight line. By the time that beam is 100 miles away from the tower, it might be 10,000 feet up in the air. It’s literally shooting over the top of the rain that’s hitting your head.

🔗 Read more: Braun Series 9 Sport: Is This Actually Different From the Regular Model?

This is why "radar gaps" are such a big deal in places like Central Oregon or parts of the South. If the beam is too high, it misses low-level rotation. It misses the stuff that actually matters to someone standing on the sidewalk.

Futurecasting and the AI Problem

Most modern apps use something called "nowcasting." They take the last few frames of a weather forecast radar map and just... slide them forward. It’s linear extrapolation. If a storm is moving east at 30 mph, the app assumes it will keep moving east at 30 mph.

But storms are living things. They breathe. They "pulse." A thunderstorm can collapse in ten minutes, or it can suddenly "turn right" because it created its own internal pressure system.

Honestly, the "Future Radar" you see on popular apps is often just a fancy animation. It doesn't always account for the thermodynamics of the atmosphere. It's just moving pixels. If you want the real story, you have to look at the "Base Reflectivity" and the "Composite Reflectivity."

- Base Reflectivity: This is the lowest tilt. It’s what is likely hitting the ground.

- Composite Reflectivity: This shows the strongest echoes at any altitude.

If the Composite is bright red but the Base is light green, the rain is likely evaporating before it hits your head. This is called virga. It looks like a storm on the screen, but the air near the ground is too dry for the water to make it down.

How to Spot a "Fake" Storm

If you see a perfectly straight line or a series of concentric circles on your map, it isn't a secret government weather machine. It’s interference. Sometimes it’s sun spikes, which happen at sunrise or sunset when the radar points directly at the sun. Sometimes it’s "blue sky returns," where the radar is so sensitive it's picking up dust or temperature inversions.

Birds and insects are another big one. During migration seasons, you can see massive "blooms" of blue and green on the weather forecast radar map shortly after sunset. That’s not a surprise rainstorm; that’s millions of birds taking off at once. Expert meteorologists can tell the difference because birds don't move like clouds, but your automated phone app might send you a "Rain starting soon" notification anyway.

✨ Don't miss: Netflix Custom Profile Picture: Why You Can’t Just Upload Your Own Photo

Dual-Pol: The Game Changer

In the last decade, we got Dual-Polarization radar. Traditional radar sent out horizontal pulses. Dual-Pol sends out both horizontal and vertical pulses.

This is massive. It allows meteorologists to see the shape of the object. Raindrops are actually flattened out like hamburger buns when they fall. Hail is a tumble-dry mess. By comparing the horizontal and vertical returns, the NWS can tell exactly what is falling.

They can even see "Tornado Debris Signatures" (TDS). This is when the radar picks up non-meteorological objects—like insulation, wood, and pieces of houses—lofted into the air. When a meteorologist sees a "Debris Ball" on the map, they don't need a visual confirmation anymore. They know a tornado is on the ground doing damage.

Reading Between the Lines

You've got to be skeptical. If an app tells you it will start raining at 2:14 PM, take it with a grain of salt. High-resolution models like the HRRR (High-Resolution Rapid Refresh) update every hour, and they are good, but they aren't perfect.

Check the "Velocity" tab if your app has one. If you see bright red next to bright green, that's "couplet" wind moving in opposite directions. That's where the trouble is. If you're just looking at the pretty rainbow colors of the reflectivity map, you're only getting half the story.

Also, look for "training." This is when storms follow each other like boxcars on a train track. The radar might not look that scary at first, but if those cells keep passing over the same spot, that's when you get flash flooding.

✨ Don't miss: Powerbeats Pro 2 Amazon: What We Know About the Shohei Ohtani Teased Release

Actionable Steps for Better Accuracy

Stop relying on the "automated" summary at the top of your weather app. It's often generated by an algorithm that misses nuance.

- Use multiple sources. Compare the NWS radar (the gold standard) with private entities like Weather Underground or RadarScope.

- Look at the loop, not the still image. Is the storm growing (becoming more colorful) or decaying (fading out)? Direction matters, but intensity trends matter more.

- Find your local NWS office on social media. Humans still beat computers at interpretation. If there is weird interference or a bird migration "bloom" on the map, a human meteorologist will point it out.

- Download a "Pro" level app. If you live in a severe weather state, spend the five bucks on RadarScope or Gibson Ridge. These apps give you the raw data without the "smoothing" filters that most consumer apps use. Smoothing makes the map look pretty, but it hides the fine details that indicate a developing microburst or a hail core.

- Check the "Echo Tops." If your app shows how high the clouds go, look for anything over 30,000 or 40,000 feet. The higher the clouds, the more energy the storm has.

Radar is a tool of probability, not a video of reality. Once you understand that the weather forecast radar map is just a collection of radio echoes being interpreted by a computer, you'll stop being surprised when that "heavy rain" turns out to be a light mist. Focus on the trends, understand the distance from the station, and always keep an eye on the velocity data when things look rough. This is how you move from being a casual observer to someone who actually understands the sky.