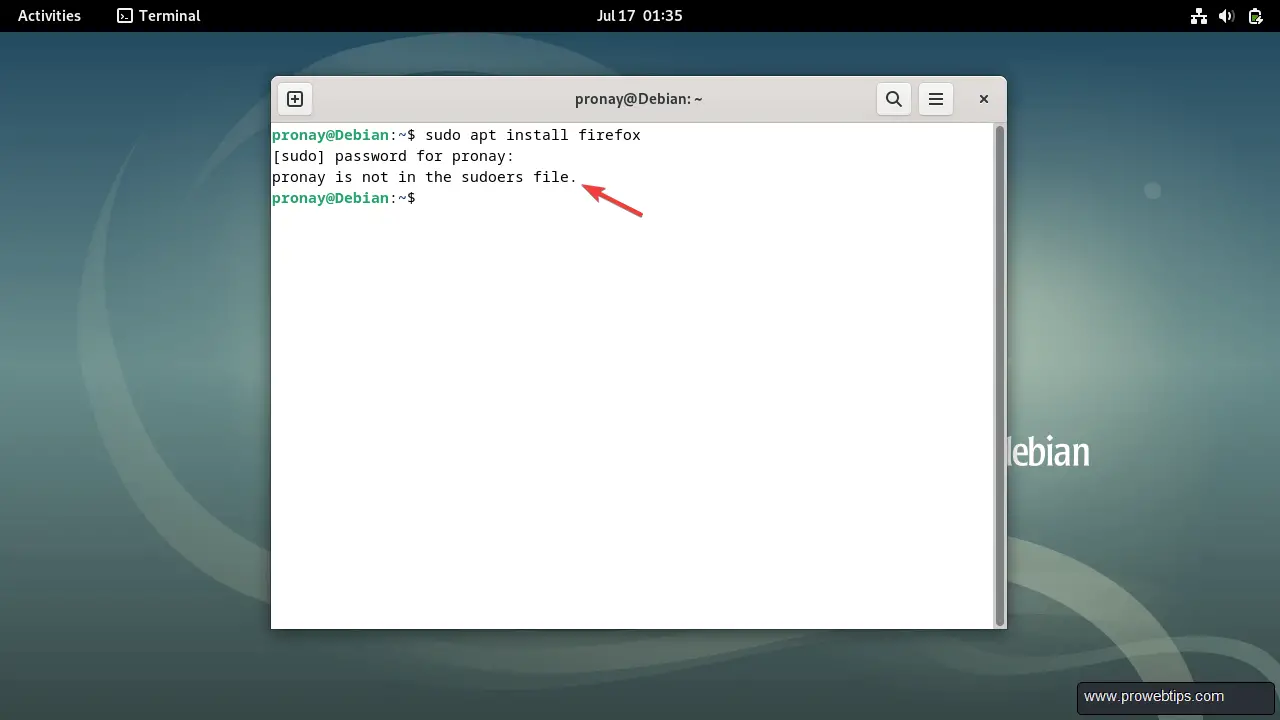

You've just finished a fresh install of Debian, or maybe you’re poking around a new server at work. You type a command—maybe something simple like apt update—and hit enter. You expect a password prompt. Instead, the terminal spits back a cold, judgmental line of text: user is not in the sudoers file. This incident will be reported. It feels like a digital slap in the face.

The "incident will be reported" part sounds ominous, doesn't it? It conjures images of a stern system administrator receiving an automated email and shaking their head at your incompetence. In reality, unless you are on a massive corporate network with specific auditing tools like auditd configured, that "report" usually just sits in a lonely log file at /var/log/auth.log that nobody ever reads. Don't panic. You aren't in trouble, but you are stuck.

Why Linux Locks You Out by Default

Most modern distributions like Ubuntu or Fedora handle this for you during the installation process. They ask for a username and then quietly add that user to a special group. On Ubuntu, it’s the sudo group. On Fedora or CentOS, it’s usually the wheel group.

But Debian? Debian is a bit of a purist.

If you leave the root password blank during a Debian installation, it gives your first user sudo privileges. If you actually set a root password, Debian assumes you want to keep the "root" account and "user" accounts strictly separate. It’s a security philosophy. The idea is that you shouldn't be wandering around with a loaded gun (sudo) unless you specifically asked for it.

The sudoers file, located at /etc/sudoers, is essentially the VIP list for your operating system. It defines who can run what, where, and how. If your name isn't on the list, the sudo (SuperUser DO) binary simply refuses to execute the command on your behalf. It’s a gatekeeper. A very effective one.

Fixing the Is Not In The Sudoers File Error

The most common way to fix this is to add your user to the appropriate group. You can't do this using sudo because, well, that's the whole problem. You have to become the actual root user first.

Type su - in your terminal.

That little dash is important. It ensures you get the root user's environment variables and path. Enter the root password you created during installation. Now, look at the prompt. It probably changed from a $ to a #. You are now the king of the mountain.

Once you are root, the command is straightforward: usermod -aG sudo yourusername.

Wait.

Check your distro first. If you are on an Arch-based system or something Red Hat-flavored, it might be usermod -aG wheel yourusername instead. The -aG flag stands for "append to group." If you forget the -a, you might accidentally remove your user from every other group they belong to, which creates a whole new nightmare.

🔗 Read more: Ripple CTO on XRP Centralization: What Most People Get Wrong

After running that, you must log out and log back in. This is the part everyone forgets. Group memberships are only refreshed at login. If you try to run sudo immediately after adding yourself to the group, it will still fail. It’s frustrating. It’s clunky. But that’s how the session management works.

The Secret Architecture of the Sudoers File

Sometimes, simply adding a user to a group isn't enough, or maybe you want more granular control. This is where the visudo command comes in.

Never, ever try to edit /etc/sudoers with a regular text editor like Nano or Vim directly. If you mess up a single character or leave a syntax error in that file, you can effectively lock everyone—including yourself—out of administrative privileges.

visudo is a wrapper. It opens the file in an editor, but when you try to save, it checks the syntax. If you made a typo, it warns you and asks if you want to fix it before committing the changes to disk. It’s your safety net.

Inside that file, you'll see lines like this:root ALL=(ALL:ALL) ALL

Basically, this says the root user, on all hosts, acting as any user or any group, can run any command. You can add a specific line for yourself if you don't want to use groups:myuser ALL=(ALL:ALL) ALL

Some people prefer the "no password" approach for specific tasks. It’s risky. It’s lazy. But if you’re running a local development VM and you’re sick of typing your password every five minutes, you might change it to myuser ALL=(ALL) NOPASSWD:ALL. Just know that if anyone gets access to your shell, they own your entire machine instantly.

When Things Go Terribly Wrong

What if you don't know the root password? Or what if you're on a system where the root account is locked (like Ubuntu) and your only sudo user just got removed from the sudoers file?

You're essentially locked out of your own house.

In this scenario, you have to go "out of band." This usually means rebooting the machine and interrupting the GRUB bootloader. You'll need to edit the boot entry—usually by pressing e—and appending init=/bin/bash or rw init=/bin/sh to the line that starts with linux.

This tells the kernel to ignore the standard startup sequence and just give you a bash prompt with root privileges. From there, you can remount the filesystem as read-write (mount -o remount,rw /) and fix the sudoers file or add your user back to the group. It’s a bit of a "hacker" move, but it’s a standard recovery procedure for Linux admins who’ve painted themselves into a corner.

The Reporting Myth

Let's circle back to that "incident will be reported" line.

I remember the first time I saw it. I was sixteen, trying to mess with a school computer, and I thought the police were going to show up at my door. I wasn't the only one. This specific string of text has been a part of the sudo source code for decades.

By default, the "report" is just a log entry. In the sudoers file, there are options like mail_badpass or mail_no_user. If those are turned on, the system will actually send an email to the postmaster (usually root) every time someone fails a sudo attempt. On a modern desktop, that email just goes into a local mailbox file that nobody ever checks.

However, in a professional DevOps or SecOps environment, these logs are often piped into a SIEM (Security Information and Event Management) system like Splunk or an ELK stack. If you're at work and you try to sudo into something you shouldn't, someone might actually notice a spike in "unauthorized sudo attempts" on their dashboard.

Better Ways to Manage Permissions

Modern Linux management has moved slightly away from manually editing the sudoers file for every single person.

If you look inside /etc/sudoers.d/, you’ll see it’s empty or has one or two files. This is the "drop-in" directory. Instead of risking the main sudoers file, you can create a new file here—say, /etc/sudoers.d/web-admins.

Inside that file, you define the permissions for a specific group of people. This keeps the configuration modular. If you want to revoke those permissions, you just delete the file. You don't have to go hunting through a 100-line config file trying to remember which line you added six months ago.

Another nuance: sudo -i.

A lot of people think sudo su is the way to get a root shell. It works, but it's messy. sudo -i (or sudo -s) is the "correct" way to do it. It keeps the logging trail clean and handles the environment variables much more gracefully.

Practical Steps to Take Now

If you're staring at that error right now, here is the sequence of events to follow.

First, determine if you have the root password. If you do, use su - to switch users. If you are on Ubuntu or a system where root is locked, you'll need to use a Recovery Mode boot or a Live USB to regain access.

Once you have root access, verify which group has sudo privileges on your specific OS. Open /etc/sudoers (with visudo!) and look for a line starting with %sudo or %wheel.

📖 Related: Why Every Picture of a Solar System You Have Seen Is Kinda Lying To You

Add your user to that group: usermod -aG [groupname] [username].

Double-check the /etc/group file to make sure your name appears next to the group.

Log out completely. Don't just close the terminal window; log out of the entire GUI session or reboot the machine.

Test it with a simple sudo whoami. If it returns "root," you've successfully fixed the "is not in the sudoers file" error and reclaimed control over your system.

Moving forward, consider using the /etc/sudoers.d/ directory for any custom permissions. It's safer, cleaner, and much harder to break. If you're managing multiple servers, look into Ansible’s lineinfile or template modules to manage sudoers across your fleet so you never have to manually touch these files again.

Security is a balance. The sudoers file is the fulcrum of that balance on a Linux system. Respect the gatekeeper, use visudo, and always keep a backup of your important data before you start messing with system-level permissions.