So, you've got a science animal cell project due. Maybe you’re a student staring at a block of Styrofoam, or a parent wondering why on earth you’re buying $40 worth of gourmet jellybeans for a middle school assignment. Honestly, most of these projects end up looking exactly the same. You see the same shoeboxes, the same clay blobs, and the same pipe cleaners representing the cytoskeleton. But here is the thing: most of those models are actually scientifically misleading.

Biology is messy.

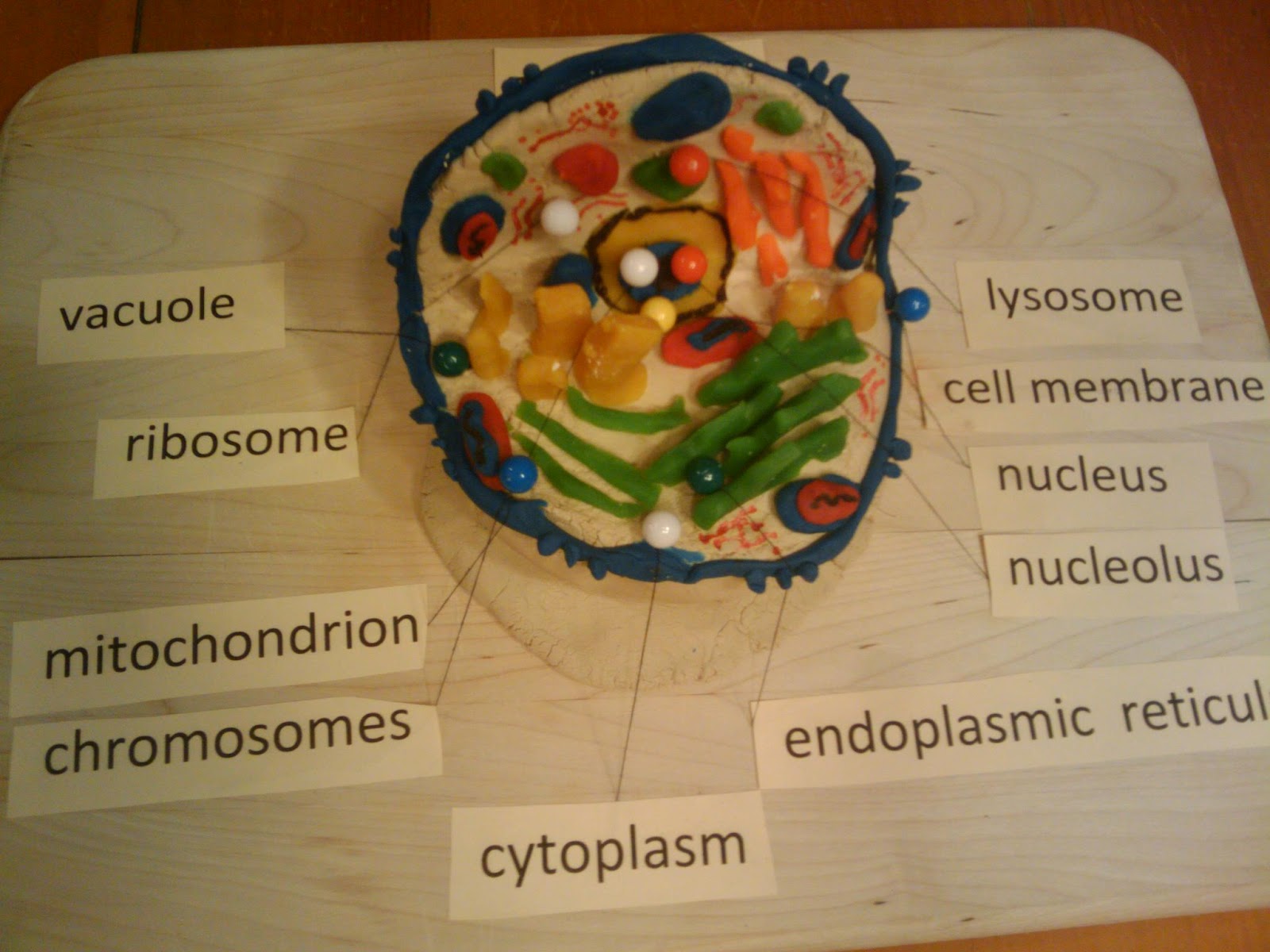

Cells aren't static cubes or perfect spheres. They are dynamic, crowded, and chaotic environments. If you want to actually nail this project—and maybe even impress a teacher who has seen five thousand identical cake cells—you have to think beyond the "parts list" mentality. It isn’t just about labeling the nucleus. It is about understanding how these microscopic machines actually function in a 3D space.

The Problem With the Standard Science Animal Cell Project

Most people treat the cell like a factory. We’ve all heard the "mitochondria is the powerhouse of the cell" line a billion times. It is a cliché for a reason, but it’s also a bit of a simplification that strips away the wonder of molecular biology. When you start your science animal cell project, the first mistake is usually scale.

In most models, the nucleus is huge, and the rest of the organelles are tiny dots floating in a sea of "cytoplasm" (which usually ends up being blue hair gel or clear resin). In reality, a cell is incredibly crowded. It’s more like a packed subway car at rush hour than a swimming pool with a few toys floating in it. Proteins are bumping into each other constantly. Molecular motors like kinesin are literally "walking" along microtubules to deliver cargo.

If you want your project to stand out, you need to capture that density. Instead of just placing one "bean" for a mitochondrion, consider how many a specific cell type actually needs. A muscle cell is going to be packed with them because it needs constant energy. A skin cell? Not so much. That kind of nuance is what moves a project from a "C" to an "A+."

Breaking Down the Must-Have Organelles (Without Being Boring)

The Nucleus is usually the star of the show. It’s the "brain," right? Well, sort of. It’s more like the library or the archive. It holds the DNA—the master blueprints. If you’re building a model, don't just make it a solid ball. The nuclear envelope has pores. These are actual gates that control what goes in and out. Maybe use a mesh material or a textured surface to show that it’s not a closed-off fortress.

Then you’ve got the Endoplasmic Reticulum (ER). This is where things get tricky for a science animal cell project. You have the Rough ER and the Smooth ER. The "rough" part comes from ribosomes, which are the sites of protein synthesis. If you’re using clay, stipple the surface with sand or glitter. It shows you know why it's called "rough." The Smooth ER is more about lipid synthesis and detoxification. They look different, they do different things, and they shouldn't just be the same squiggle in different colors.

The Golgi Apparatus: The Cell's Post Office

Everyone calls the Golgi the post office. It packages proteins into vesicles and sends them where they need to go. But here is a cool detail: the Golgi has a "front" and a "back" (the cis and trans faces). It’s a directional processing plant. If you’re building this, try to show the vesicles actually "budding" off the edges. It gives the model a sense of movement.

Mitochondria: More Than Just Powerhouses

We have to talk about them. Mitochondria have their own DNA. Let that sink in. They were likely once independent bacteria that were swallowed by a larger cell billions of years ago—a process called endosymbiosis. When you draw or build your science animal cell project, draw those inner folds (the cristae). That’s where the actual chemistry happens. More surface area equals more energy production. It’s a brilliant piece of biological engineering.

Choosing the Right Materials for Your Model

Forget the "cell cake" unless you’re okay with it attracting ants or getting soggy by the time you present it. If you want something that lasts and actually looks professional, you have to get creative with textures.

- Clear Slime or Resin: This is great for cytoplasm because it’s viscous. It holds the organelles in place but lets you see through it. Just be careful with bubbles.

- 3D Printing: If you have access to a 3D printer, this is the gold standard. You can download STL files of actual protein structures from databases like the PDB (Protein Data Bank).

- Recycled Electronics: Use old wires for the cytoskeleton and circuit board pieces for the Golgi. It gives a "bio-mechanical" look that is very popular in modern science communication.

- Soft Sculptures: Needle felting or sewing organelles out of felt can make for a tactile, durable model that won't break if you drop it on the bus.

Why 2D Posters Still Matter

Sometimes a 3D model isn't required. A 2D science animal cell project can actually show more detail because you aren't fighting gravity. The key here is cross-sections. Don't just draw circles. Use "cutaway" views.

Show the phospholipid bilayer of the cell membrane. It’s not just a skin; it’s two layers of fats with heads that love water and tails that hate it. Illustrating those individual molecules shows a level of depth that a simple line can't match.

You should also look into the work of David Goodsell. He is a structural biologist and artist who creates these incredible, scientifically accurate paintings of the cellular interior. His work is a masterclass in showing how crowded and beautiful a cell really is. If you base your color palette or layout on his style, your project will look sophisticated and academic.

Common Misconceptions to Avoid

One of the biggest mistakes in a science animal cell project is including a cell wall or a large central vacuole. Those are for plants. Animals have small, temporary vacuoles. We also have centrioles, which plants generally don't. Centrioles are these barrel-shaped structures that help with cell division. They look like little bundles of pasta. Including them shows you know the specific differences between kingdoms.

Another thing? The "empty space." There is no empty space. The cytoplasm is filled with a network of fibers called the cytoskeleton—microtubules, actin filaments, and intermediate filaments. This isn't just "filler." It’s the scaffolding that gives the cell its shape and allows it to move. If your model doesn't have some sort of thread or wire connecting things, it’s technically "floating," which isn't how biology works.

🔗 Read more: Montana State University Out of State Tuition Explained (Simply)

Making Your Project "Discoverable" and Interactive

If this is for a science fair or a digital submission, think about interactivity. Maybe you include QR codes next to each organelle that link to a short video of it in action. Or perhaps you use augmented reality (AR) apps to overlay information on your physical model.

The goal of a science animal cell project isn't just to prove you can follow instructions. It is to prove you understand the logic of life. When you explain your project, don't just read the labels. Explain the workflow. "The DNA in the nucleus sends a message to the ribosomes on the Rough ER, which makes a protein, which goes to the Golgi to be tagged, and then it’s shipped out of the cell membrane." That’s a story. Teachers love stories.

Practical Steps for a Winning Project

Start with a plan. Don't just start gluing things.

- Pick a specific cell type. Instead of a "generic" animal cell, do a neuron or a red blood cell. It makes the project unique and gives you a specific shape to work with.

- Scale your organelles. Use a rough ratio. The nucleus shouldn't take up 90% of the space unless it's a very specific type of immune cell.

- Use a "Key" or Legend. Instead of sticking big, ugly labels directly on the model, use small numbered pins and a separate, neatly printed key. It keeps the model looking clean.

- Focus on the Membrane. Spend time on the outer boundary. It’s the gatekeeper. Showing "integral proteins" (the tunnels through the membrane) is a huge E-E-A-T (Experience, Expertise, Authoritativeness, and Trustworthiness) boost for your project.

- Check your facts. Double-check the difference between lysosomes and peroxisomes. They both break things down, but they use different chemicals to do it.

When you're finished, take high-quality photos in natural light. If you're posting this online or submitting it digitally, clarity is everything. A great science animal cell project is a mix of art and hard data. It’s about showing that even at a scale we can't see with the naked eye, there is a staggering amount of organization and "intent" in every living thing.

👉 See also: Jordan 12 Retro Flu Game 2025: Why the Hype is Actually Real This Time

Get the textures right. Get the crowding right. Tell the story of the protein's journey. If you do those things, you aren't just making a school project; you're creating a piece of scientific communication that actually means something. Use real materials that reflect the "vibe" of the organelle—squishy for the fluid parts, rigid for the structural parts. It makes the science feel real.