The Rockies are massive. They stretch over 3,000 miles, carving a jagged spine through North America that basically dictates the weather, the water, and where people can actually live. When you look at a rocky mountains physical map, you’re seeing more than just some brown bumps on a page; you're looking at the tectonic aftermath of a massive geological collision that happened millions of years ago. Most people think it’s just one long, continuous wall of stone. It isn’t.

It’s a mess of distinct ranges, high plateaus, and deep basins.

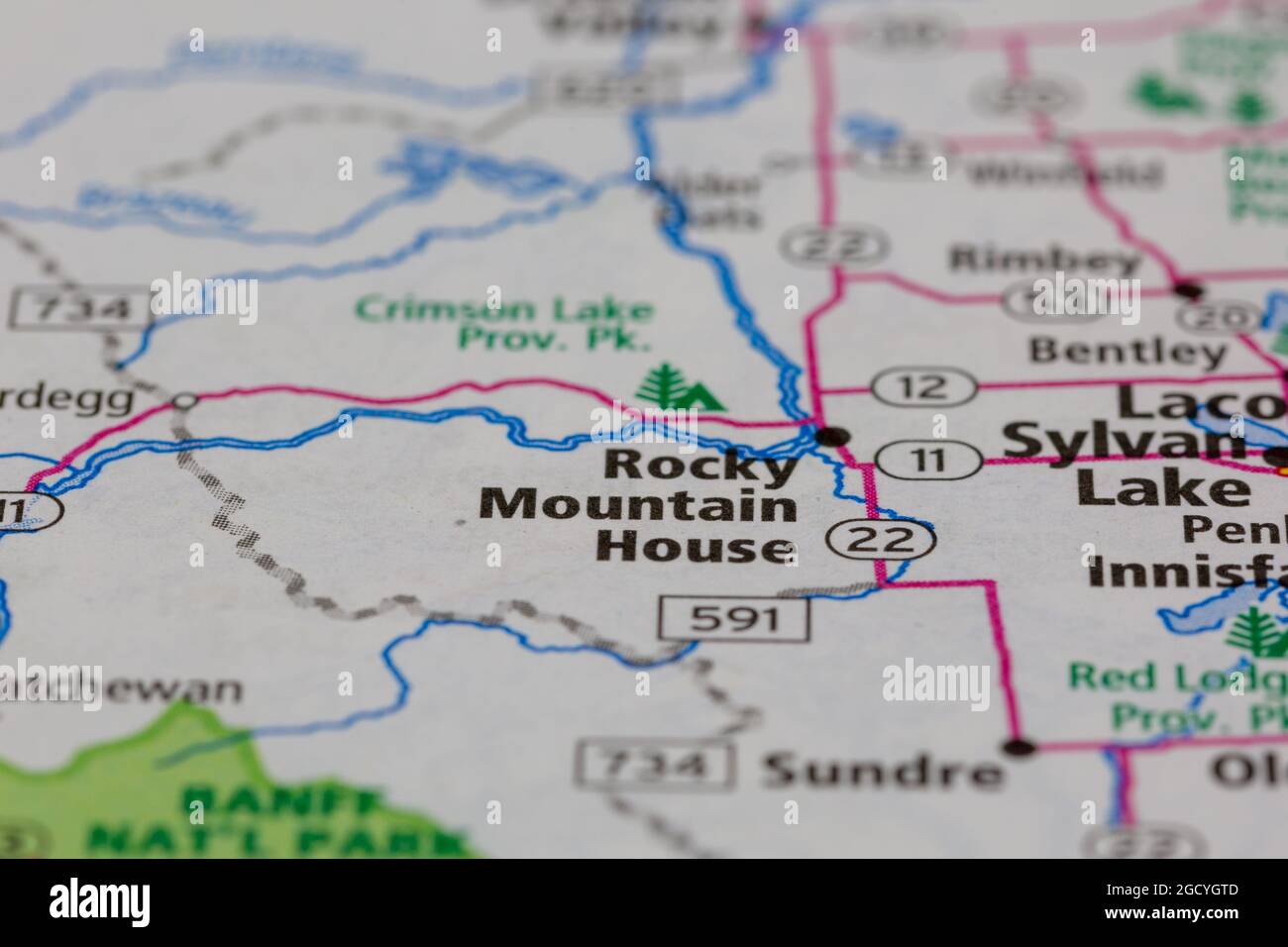

If you’re staring at a map of the United States or Canada, the first thing that jumps out is the sheer breadth. We aren't talking about a single ridge like the Appalachians. The Rockies are a province. Geologically speaking, they are a "cordillera." This means they are a complex system of mountain chains that run parallel to each other. From the Liard River in British Columbia all the way down to the Rio Grande in New Mexico, the terrain shift is radical. You go from the glaciated, razor-sharp peaks of the Canadian Rockies to the red-tinted, semi-arid ranges of the American Southwest. It’s a lot to process at once.

Reading the Layers of a Rocky Mountains Physical Map

When you zoom in on a high-quality physical map, you’ll notice the color coding isn't just for aesthetics. The dark browns represent the high alpine zones—places like the Front Range in Colorado or the Wind River Range in Wyoming. Here, peaks regularly exceed 14,000 feet. These are the "Fourteeners." If you’ve ever been to Denver, you know the Front Range looks like a literal wall rising out of the plains. That’s the Laramide Orogeny talking. That was the mountain-building event between 80 and 55 million years ago that pushed these rocks up.

But look closer at the map. Notice the gaps?

👉 See also: Finding Brownsville on Texas Map: Why This Border City Is Actually the Future

Those are the basins. The Wyoming Basin is a huge one. It’s a high-altitude "hole" in the mountains that allowed early pioneers—and today’s Interstate 80—to cross the Continental Divide without actually climbing over a 12,000-foot pass. Without that specific physical feature, the westward expansion of the U.S. would have looked completely different. Map geeks call this "topographic prominence." It’s basically a measure of how much a peak stands out from its surroundings. In the Rockies, prominence is everything.

The Canadian vs. American Divide

The northern section of the Rockies, mostly in Canada, feels different on a map because it is different. It’s dominated by sedimentary rock—limestone and shale. This is why the peaks in Banff or Jasper look so much pointier and more "layered" than the granite domes of Colorado. The glaciers did a number on them. During the last ice age, massive sheets of ice carved out U-shaped valleys that are so deep they almost look fake on a 2D map.

Down south, the Colorado Rockies are wider and bulkier. You have the Sawatch Range, which contains Mount Elbert, the highest point in the entire chain at 14,440 feet. If you’re looking at a rocky mountains physical map, the Colorado section is the most densely packed with high-elevation territory. It’s like the "roof" of North America.

The Continental Divide: The Invisible Line

You can't talk about a physical map of this region without mentioning the Continental Divide. It’s that jagged, dotted line that zig-zags through the peaks. Honestly, it’s the most important hydrological feature on the continent. If a raindrop falls an inch to the west of that line, it’s headed for the Pacific Ocean. An inch to the east? It’s going to the Gulf of Mexico or the Atlantic.

This line isn't just a fun fact for hikers. It determines water rights for millions of people. States like California, Arizona, and Nevada are basically kept alive by water flowing off the western slopes of the Rockies via the Colorado River. When you see the blue lines on a map snaking away from the high peaks, you’re looking at the lifeblood of the American West. The Green River, the Snake, the Arkansas—they all start as snowmelt in these high-altitude catchments.

Volcanic Interlopers and Hidden Valleys

Sometimes, people get confused by the San Juan Mountains in Southwest Colorado. On a physical map, they look different. They’re more rugged and colorful. That’s because they are largely volcanic. While most of the Rockies were pushed up by tectonic plates sliding under each other, the San Juans were shaped by massive volcanic eruptions.

Then you have the "parks."

In the Rockies, a "park" isn't always a place with swings and slides. It’s a high-altitude basin. North Park, Middle Park, and South Park in Colorado (yes, that South Park) are vast, flat grasslands surrounded by 13,000-foot peaks. On a physical map, these look like huge green or light-tan circles nestled inside the dark brown mountain ridges. They are essentially ancient lake beds or structural depressions. They’re cold, windy, and beautiful.

Flora, Fauna, and the Vertical Desert

A physical map also hints at the ecology through shaded relief and vegetation layers. The Rockies are essentially "vertical islands." At the base, you might have a high-desert environment with sagebrush and cacti. As you move up the map—and the mountain—you hit the montane zone (Ponderosa pines), then the subalpine zone (Spruce and Fir), and finally the alpine tundra.

The tundra is the part of the map above the "treeline." In the southern Rockies, this is usually around 11,500 feet. In the north, it’s much lower. Above this line, it’s too cold and the growing season is too short for trees to survive. It’s a land of lichen, hardy grasses, and pikas. If you see a map with grey or white shading on the very tips of the mountains, that’s either permanent snowfields or the rocky barrens of the alpine zone.

Key Features to Spot on Your Map:

- The Grand Tetons: Located in Wyoming, these are "fault-block" mountains. They lack foothills, meaning they rise straight up from the valley floor. It’s one of the most dramatic sights in the world.

- The Bitterroot Range: Forming the border between Idaho and Montana, this is some of the most rugged, roadless wilderness in the lower 48.

- The Sangre de Cristo Mountains: The southernmost subrange, stretching into New Mexico. They are narrow, steep, and incredibly dramatic at sunset.

- The Columbia Mountains: Often lumped in with the Rockies, but geologically distinct. They sit just to the west in BC and get way more snow.

Why Scale and Projection Matter

If you’re trying to use a rocky mountains physical map for actual navigation, you need to pay attention to the scale. These mountains are deceptive. On a large-scale map, two peaks might look like they are right next to each other. In reality, there could be a 3,000-foot canyon between them that takes six hours to cross.

Topographic maps—the ones with the "swirly lines" (contour lines)—are the only way to truly understand the physical shape of the land. Each line represents a specific elevation. When the lines are close together, it’s a cliff. When they’re far apart, it’s a gentle slope. Expert mountaineers spend years learning to "see" the 3D landscape just by looking at these 2D lines.

Human Impact on the Physical Landscape

It’s worth noting that a modern physical map also shows how we’ve tried to tame this vertical wilderness. You’ll see the thin red lines of mountain passes like Loveland Pass or the Eisenhower Tunnel. You’ll see the massive reservoirs like Lake Powell or Lake Mead, which are essentially giant buckets catching the Rockies' runoff.

Even the "physical" aspect of the map is changing. Glaciers in places like Glacier National Park are shrinking. On maps from 50 years ago, the white patches representing permanent ice were much larger. Today, cartographers are literally redrawing the boundaries of these features as the ice retreats. It’s a sobering reminder that even the "everlasting" hills are in a state of flux.

Actionable Steps for Exploring the Rockies

If you're planning to move from looking at a map to actually standing on the dirt, you need to prepare for the reality of high-altitude geography. The map doesn't tell you about the oxygen—or the lack of it.

- Check the SNOTEL data. SNOTEL stands for "Snow Telemetry." It’s a network of automated sensors throughout the Rockies that tells you exactly how much snow is on the ground at specific elevations. If the map shows a trail at 10,000 feet, check SNOTEL before you go in June; it might still be under six feet of snow.

- Understand "Aspect." In the Rockies, the direction a slope faces (its aspect) changes everything. North-facing slopes hold snow longer and have thicker forests. South-facing slopes are drier and more likely to have clear trails early in the season. Use your map to determine which side of the mountain you’ll be on.

- Download offline maps. Cell service is non-existent in about 90% of the Rocky Mountain chain. Use apps like Gaia GPS or OnX to download high-resolution topographic layers before you leave the trailhead.

- Acclimatize. If your map shows you starting at 5,000 feet and going to 12,000, don't do it on day one. Your body needs time to produce more red blood cells to carry oxygen. Spend a night at the "base" elevation before heading into the high country.

The Rockies are a geological masterpiece. Whether you're studying the Laramide Orogeny or just trying to find a cool place to camp, the physical map is your primary tool for understanding how this continent is built. It’s a vertical world, and every contour line tells a story about time, pressure, and the relentless power of water and ice. Stay safe out there and always carry a paper backup; batteries die, but the map remains.