History isn't a straight line. When you look at a revolutionary war battles map, you usually see a bunch of red and blue dots scattered across the thirteen colonies like someone spilled a bowl of patriotic cereal. It looks organized. It looks intentional. But honestly? The war was a chaotic, muddy mess that barely followed any logic at all. If you’re trying to understand how a group of ragtag farmers beat the most powerful empire on the planet, a static map only tells you about 10% of the story. You’ve gotta look at the space between the dots to see what actually happened.

Geography was the ultimate protagonist.

Most people start their journey at Lexington and Concord because, well, that's where the shooting started in 1775. But if you look at a map of that specific day, it’s not a "battle" in the way we think of Gettysburg or Waterloo. It’s a running narrative of a retreat. The British were basically trapped on a single road, surrounded by woods and stone walls that acted as natural sniper nests. It was a linear nightmare.

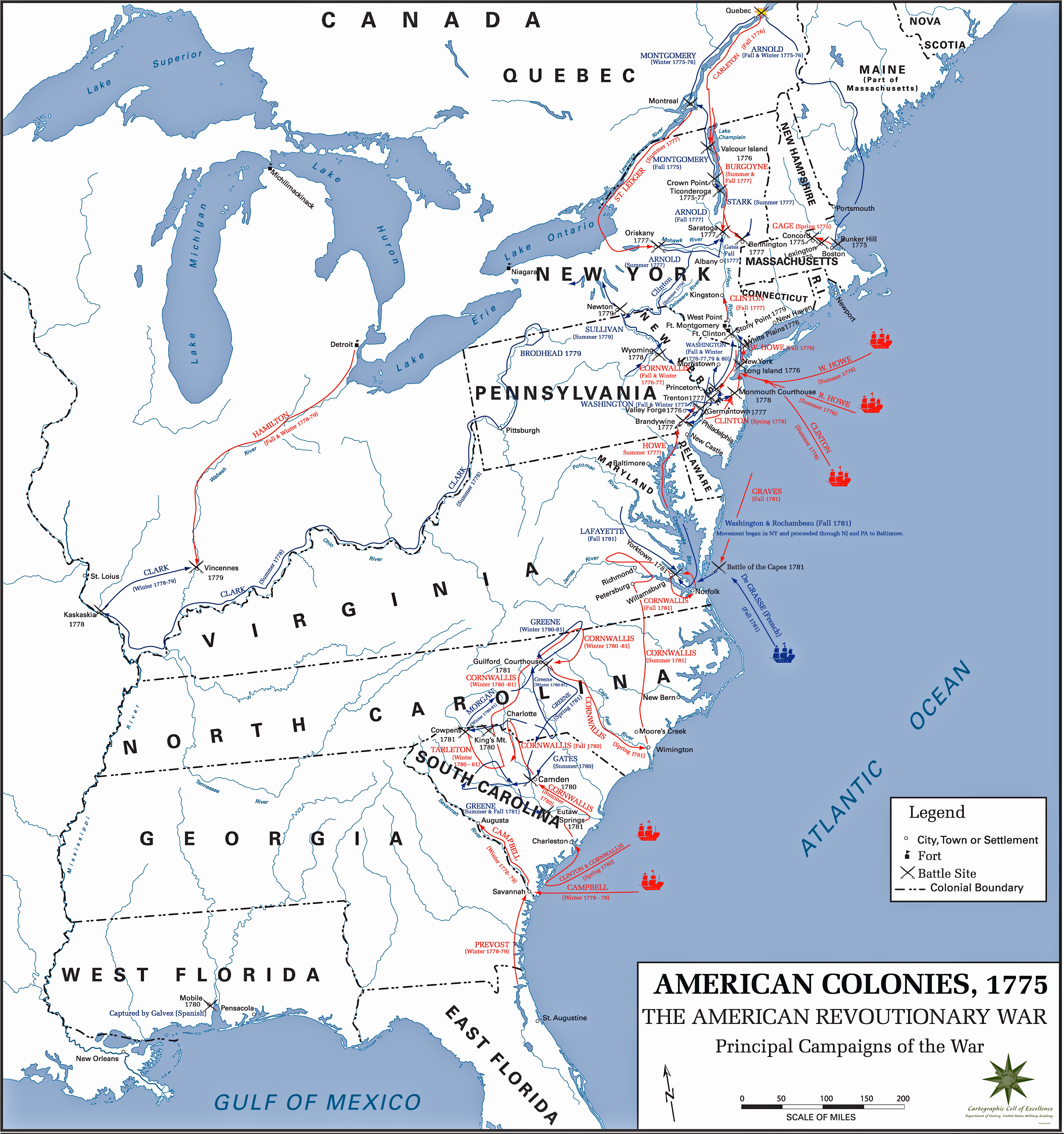

The Northern Theater: It Was All About the Water

Look at the Hudson River. If you find a revolutionary war battles map that doesn't emphasize the "Great North Woods" and the water corridor from Canada to New York City, toss it in the trash. This was the strategic spine of the continent. The British obsession with the Hudson—basically trying to slice the colonies in half like a loaf of bread—is why we have the Battle of Saratoga.

Saratoga is often called the "turning point," which is a bit of a cliché, but it's true for a reason. British General John Burgoyne was trying to move south from Quebec. He had a massive baggage train. We’re talking about mobile wardrobes, fine china, and champagne. This wasn't exactly "traveling light." Because the terrain was so thick with old-growth forest and swampy marshes, his army could only move a few miles a day. Meanwhile, the Americans were busy chopping down trees to block the roads.

By the time Burgoyne reached the heights above the Hudson, he was exhausted and undersupplied. The resulting American victory at Freeman's Farm and Bemis Heights wasn't just about superior shooting; it was about the British failing to understand the sheer scale of the American wilderness. When you see those red dots at Saratoga on your map, remember they represent a logistical collapse caused by the very ground they stood on.

The New York Catastrophe

Conversely, look at the cluster of dots around Manhattan. In 1776, George Washington almost lost the entire war there. A map of the Battle of Long Island shows a disastrous "outflanked" movement. The British landed at Gravesend and used a forgotten pass—the Jamaica Pass—to get behind the American lines. Washington was pinned against the East River.

It was a total failure of intelligence. Honestly, the only reason the Revolution didn't end in August 1776 was a literal fog that rolled in, allowing the Americans to row across the river to Manhattan under the cover of darkness. History hangs on weather patterns as much as musketry.

The Southern Strategy: Why the Map Shifts After 1778

After Saratoga, the British got frustrated. They shifted their focus south, thinking there were more Loyalists in the Carolinas and Georgia who would help them. This is where your revolutionary war battles map starts to look really different. The distances get longer. The battles get "smaller" in terms of troop numbers but way more vicious.

Take the Battle of Kings Mountain. It’s a tiny dot on the border of North and South Carolina. But it was a civil war within a revolution. Almost everyone fighting there was American—Loyalist versus Patriot. There were hardly any "Redcoats" involved. It was a brutal, uphill fight on a rocky ridge that broke the momentum of the British Southern campaign.

Then you have Cowpens. If you study the map of Cowpens, you see Daniel Morgan’s "double envelopment." It’s one of the only times in history a smaller force successfully surrounded a larger, more professional one. Morgan used the topography—a slight rise in the ground—to hide his main force, tricking the British into thinking the Americans were retreating.

- Guilford Courthouse: A tactical British "win" that was actually a strategic loss because they lost so many men they had to retreat to the coast.

- The Siege of Savannah: A failed Franco-American attempt to retake a key port.

- The Battle of Camden: A total collapse of American forces where Horatio Gates (the "hero" of Saratoga) famously fled the field on a fast horse, leaving his men behind.

Mapping the Final Move to Yorktown

The endgame in 1781 is the most satisfying part of the revolutionary war battles map to track. It’s a giant pincer movement. You have Washington and the French General Rochambeau marching all the way from New York to Virginia. Simultaneously, you have the French fleet sailing up from the Caribbean to block the Chesapeake Bay.

Lord Cornwallis, the British commander, was backed into a corner in a small tobacco port called Yorktown. He thought the Royal Navy would come to save him. They didn't. The "Battle of the Capes" happened out at sea—no ground troops, just ships—and it's arguably the most important dot on the whole map. Without the French winning that naval battle, Yorktown wouldn't have mattered.

Cornwallis was trapped between a massive trench system on land and a hostile fleet at sea. He surrendered. The war didn't technically end that day, but the "will" to keep fighting in London died right then and there.

What Most People Get Wrong About These Maps

We tend to look at these maps and see "front lines." There were no front lines.

The Revolutionary War was a series of disconnected outbursts. You could be living in a town in Pennsylvania and never see a soldier for years, while a few miles away, a skirmish was burning down a neighbor's barn. It was partisan warfare. It was messy.

Also, we often ignore the Western frontier. If your revolutionary war battles map doesn't show George Rogers Clark’s campaign in the Illinois country, you’re missing a huge piece of the puzzle. He was capturing British outposts like Vincennes with just a handful of men, effectively securing the "Old Northwest" for the future United States. Without those tiny, remote dots, the U.S. might have been trapped east of the Appalachians forever.

Logistics: The Invisible Map

Behind every battle dot is a supply line. The Americans were constantly "on the move" because they couldn't stay in one place long enough to eat everything. They were starving. Valley Forge isn't a battle, but it’s a critical point on the map because it shows the endurance required to stay in the game.

The British had the opposite problem. Their supply line was 3,000 miles long across the Atlantic Ocean. Every biscuit, every lead ball, and every replacement uniform had to cross the sea. When you look at the map, remember that for the British, every mile they moved inland was a mile further away from their lifeline.

💡 You might also like: One Way Flights to Fort Lauderdale: Why You’re Probably Paying Too Much

Actionable Insights for History Buffs

If you’re planning to visit these sites or just want to study them more deeply, don't just stare at a digital screen. You need to feel the elevation.

- Check the Topography: Use Google Earth’s 3D view when looking at Saratoga or Kings Mountain. You’ll immediately see why the "High Ground" was such a big deal. The steepness of those hills is no joke.

- Follow the Waterways: Trace the path from Lake Champlain down the Hudson. It explains about 40% of the entire war's movements in the north.

- Visit the "Small" Parks: Everyone goes to Yorktown, but places like Cowpens or Monmouth Court House often have better-preserved landscapes that give you a clearer sense of the actual combat distances.

- Look for "Point of Interest" Layers: When using a revolutionary war battles map, toggle on layers for historical markers. Sometimes the most interesting skirmishes happened in what is now a suburban Target parking lot or a quiet residential street in New Jersey.

- Overlay Colonial Roads: Find a map that shows 18th-century "Post Roads." The armies didn't march through the woods; they marched on specific, muddy tracks. If you know where the roads were, the battle locations finally make sense.

Understanding the geography is the difference between memorizing dates and actually understanding how an empire fell. The map is a living document of mistakes, lucky breaks, and the brutal reality of 18th-century travel. Next time you see a dot, look at the hills around it. That's where the real story is hiding.