You’re staring at it. Maybe it’s an X-ray you just got back from the podiatrist, or perhaps it’s a glossy diagram in a biology textbook. Either way, a picture of bones of the foot usually looks like a chaotic jigsaw puzzle that someone tried to put together in the dark.

It’s messy.

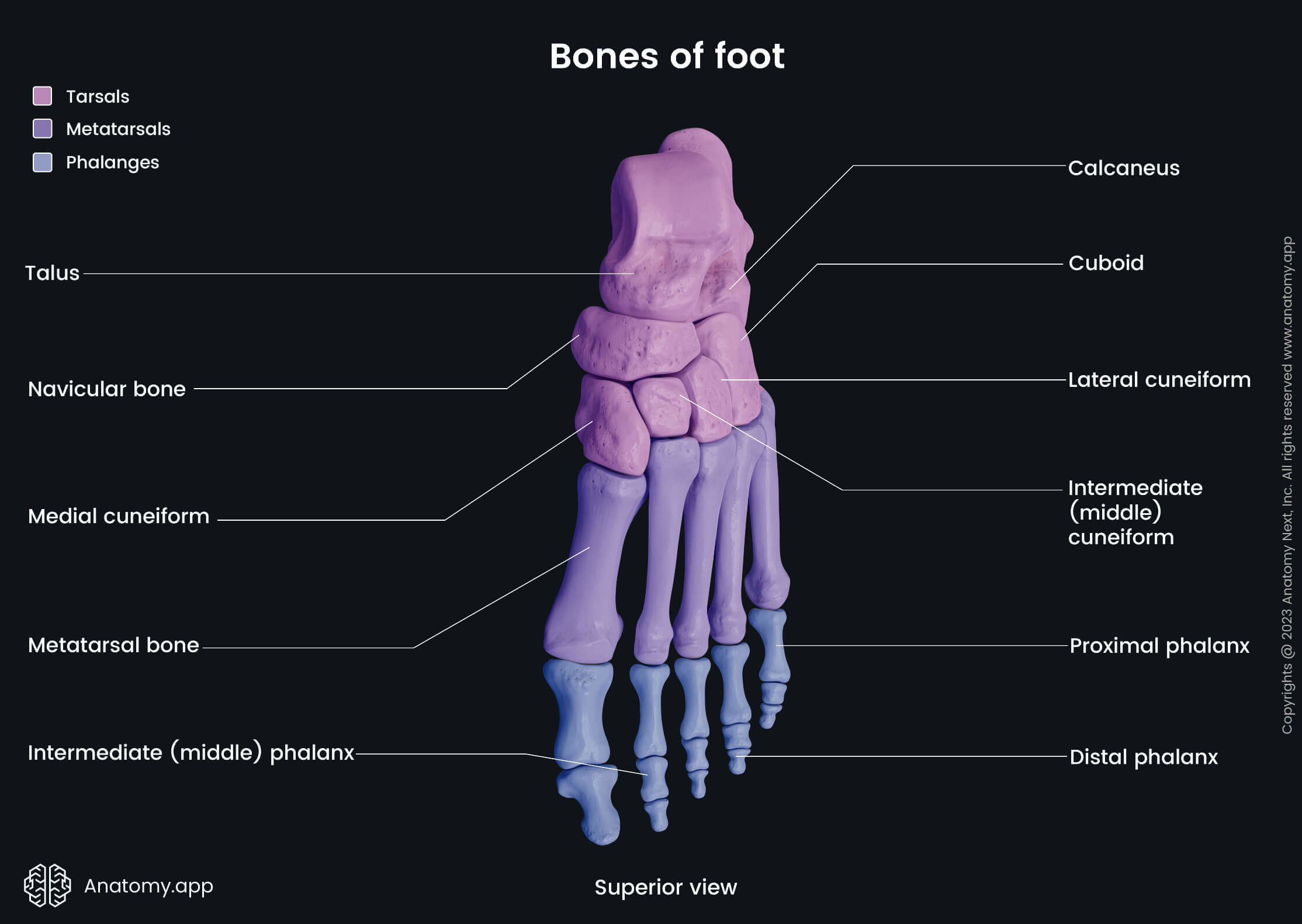

There are twenty-six bones in each foot. That’s about a quarter of all the bones in your entire body, crammed into two relatively small appendages that spend most of their lives trapped in socks. Why so many? If the foot was just one solid block of bone, you wouldn’t be able to walk on uneven ground. You’d basically be walking on stilts. Instead, your feet are architectural masterpieces designed to absorb shock, propel you forward, and keep you from falling over when you’re standing in line at the grocery store.

Honestly, most people can’t tell a cuneiform from a cuboid, and that’s fine. But when you start looking at a high-resolution image of these structures, you realize that every little bump and ridge has a job. If one of those tiny pieces is even slightly out of alignment, your whole gait changes. Your knees start to hurt. Your lower back screams. It’s all connected, and it all starts with this complex pile of calcium and collagen.

The Three Zones You’ll See in a Picture of Bones of the Foot

When you look at a medical illustration or an X-ray, it’s easiest to break the foot down into three distinct regions. Doctors call these the hindfoot, the midfoot, and the forefoot.

The hindfoot is the foundation. It’s made up of the talus—which sits right under your shin bone—and the calcaneus. The calcaneus is your heel bone. It’s the largest bone in the foot and bears the brunt of your weight every time your heel strikes the pavement. If you’ve ever had a heel spur, you know exactly where this bone is. It’s a thick, sturdy chunk of bone because it has to be.

Moving forward, you hit the midfoot. This is the "arch" area. It’s a collection of five irregular bones: the navicular, the cuboid, and the three cuneiform bones (medial, intermediate, and lateral). In a picture of bones of the foot, these look like a row of cobblestones. They don't move much, but they provide the structural stability that allows your foot to act as a rigid lever when you push off the ground.

👉 See also: Core Fitness Adjustable Dumbbell Weight Set: Why These Specific Weights Are Still Topping the Charts

Finally, there’s the forefoot. This is where things get spindly. You’ve got five metatarsals—the long bones in the middle—and then the phalanges, which are your toe bones. Your big toe only has two phalanges, while the rest of your toes have three. It’s kind of weird when you think about it, but that shorter, sturdier big toe is what gives you the power to balance. Without a strong big toe, you’d be constantly tipping over.

Why the Talus is the Weirdest Bone in the Image

If you zoom in on a picture of bones of the foot, look for the bone that sits highest up, wedged between the heel and the leg. That’s the talus. It’s a bit of an anatomical freak.

Unlike almost every other bone in your body, the talus has no muscle attachments. None. It’s held in place entirely by ligaments and other bones. It’s also covered mostly in articular cartilage. This makes it incredibly smooth, allowing your ankle to pivot and flex. However, because it has a very limited blood supply compared to other bones, if you fracture it, it heals incredibly slowly. Surgeons hate talus fractures. They often lead to something called avascular necrosis—which is basically the bone tissue dying because it isn't getting enough "food" from the blood.

When you see a lateral view (from the side) of the foot bones, the talus looks like a rounded saddle. It has to be that shape to allow the tibia and fibula to glide over it. If that saddle shape is deformed or arthritic, every single step feels like glass in the joint.

The Hidden Sesamoids

Look really closely at the "ball" of the foot in a skeletal image. See those two tiny, pea-shaped bones tucked under the head of the first metatarsal? Those are the sesamoids.

They aren't actually connected to other bones by joints; they’re embedded inside a tendon. They act like tiny pulleys. By giving the tendon a bit of extra leverage, they allow the big toe to push off with much more force than it could on its own. Athletes often get "sesamoiditis," which is just a fancy way of saying those little peas are inflamed. It’s a tiny detail in a picture of bones of the foot, but it’s the difference between sprinting and limping.

✨ Don't miss: Why Doing Leg Lifts on a Pull Up Bar is Harder Than You Think

Reading an X-Ray vs. a Diagram

There’s a massive difference between a colorful anatomical drawing and a real-life X-ray. In a drawing, everything is color-coded and clearly separated. In a real picture of bones of the foot taken in a clinic, the bones often overlap. This is called "superimposition."

For example, on a standard side-view X-ray, the three cuneiform bones often look like one big blob. Radiologists have to take "oblique" views—tilting the foot at an angle—just to see the gaps between them.

- Radiodensity: In a real image, the whiter the bone looks, the denser it is.

- Joint Spaces: You aren't actually looking for the bones; you're looking for the black space between them. That's where the cartilage lives. If the bones are touching, the cartilage is gone. That's arthritis.

- Alignment: Doctors look at the "Cyma line," an S-shaped curve formed by the joints in the midfoot. If that line is broken, the foot's mechanics are usually a mess.

It’s also worth noting that kids’ feet look totally different in pictures. If you look at an X-ray of a five-year-old’s foot, it looks like the bones are floating. That’s because much of their skeleton is still made of radiolucent cartilage that hasn't hardened into bone (ossified) yet. The "picture" isn't missing pieces; the pieces just haven't turned into "rock" yet.

Common Issues Caught in These Images

Most people only search for a picture of bones of the foot because something hurts. Maybe you kicked a coffee table or you’re worried about a bunion.

A bunion (Hallux Valgus) is very obvious in a skeletal view. You’ll see the first metatarsal drifting outward while the big toe bones point inward toward the other toes. It’s not just a "bump" on the skin; it's a structural shift of the entire medial column of the foot.

Then there are stress fractures. These are tiny cracks that might not even show up on a standard X-ray for several weeks. Doctors often need an MRI or a CT scan to see the "bone edema" or swelling inside the bone itself. If you see a tiny, hair-thin line across the neck of the second metatarsal in an image, that’s usually a classic "march fracture," common in runners or hikers who overdo it.

🔗 Read more: Why That Reddit Blackhead on Nose That Won’t Pop Might Not Actually Be a Blackhead

Lisfranc injuries are another big one. This happens at the junction between the midfoot and forefoot. In a picture of bones of the foot, look at the gap between the first and second metatarsals. If that gap is wider than a few millimeters, it usually means the Lisfranc ligament is torn. It’s a devastating injury for athletes because that tiny gap ruins the entire stability of the arch.

How to Protect Your Foot Architecture

So, what do you do with this information? Understanding the layout of these twenty-six bones should change how you treat your feet.

First, stop wearing shoes that squeeze those phalanges together. Your toes need to splay to balance your weight. When you see a picture of bones of the foot shoved into a high heel or a narrow dress shoe, you can actually see the bones being forced out of their natural alignment. Over time, the ligaments stretch or tighten, and that "temporary" squishing becomes a permanent deformity.

Second, support your arches but don't "turn them off." Your foot bones are designed to flex. If you wear orthotics that are too rigid for too long, the small muscles (the intrinsics) that support those bones can atrophy. It’s a balance. You want enough support to prevent the bones from collapsing, but enough freedom that the bones can do their job of absorbing impact.

If you are looking at a picture of bones of the foot because of a recent injury, pay attention to where the swelling is. Swelling over the "outside" middle part of the foot often points to the fifth metatarsal—the bone that sticks out a bit on the side. This is a common spot for Jones fractures, which are notorious for not healing because of—you guessed it—poor blood supply.

Real-World Action Steps

- Check your shoes for "Toe Spring": If the front of your shoe curves up aggressively, it's holding your toe bones in an extended position, which can strain the metatarsals. Look for flatter profiles for natural bone alignment.

- Strengthen the "Short Foot": Try to pull the ball of your foot toward your heel without curling your toes. This engages the bones in the arch and keeps them tight.

- Get a Weight-Bearing X-ray: If you ever need medical imaging, ask for a "weight-bearing" view. A picture of bones of the foot taken while you are sitting down is almost useless for diagnosing functional problems because the bones only shift into their "problem" positions when you're actually standing on them.

- Palpate the Navicular: Find the bony bump on the inside of your foot, about halfway between your ankle and your big toe. That's the navicular. It's the "keystone" of your arch. If that bone feels low or hurts when you press it, your arch might be collapsing.

The human foot is a piece of engineering that even the best roboticists struggle to replicate. Those twenty-six bones work in a symphony of movement that we mostly take for granted until a "clink" in the system makes every step a chore. By understanding the visual map of these structures, you’re better equipped to talk to doctors, choose better footwear, and honestly, just appreciate the sheer complexity of what’s happening inside your shoes every time you take a stroll.