Fear is weird. We spend our whole lives trying to feel safe—locking doors, checking backseats, installing Ring cameras—and then we pay ten bucks to sit in a dark room and get the life scared out of us. It makes no sense, honestly. But there is something specific about a scary horror story short that hits differently than a two-hour movie or a 500-page novel. It’s the compression. You don't have time to get comfortable with the characters or the setting. You’re just dropped into the deep end of the pool, and usually, there’s something rhythmic scratching at the tile floor beneath your feet.

Short-form horror is having a massive moment right now. You see it on Reddit’s r/nosleep, in the "two-sentence horror" trends on TikTok, and in high-end literary journals. People are busy. We want that shot of adrenaline, that prickle on the back of the neck, and we want it before our lunch break ends.

The Anatomy of a Scarier Story

Why does one story make you chuckle while another makes you refuse to let your feet hang over the edge of the bed? It’s not just about gore. Gore is easy. Gore is gross, but it isn’t always scary. Real dread comes from the "uncanny." This is a concept popularized by Ernst Jentsch and later Sigmund Freud, describing something that is simultaneously familiar yet somehow "off." Think of a doll that looks just a little too human. Or a voice coming from the baby monitor that sounds exactly like your spouse, even though you just watched them pull out of the driveway.

A great scary horror story short uses this brevity to its advantage. In a novel, a writer has to explain the monster. They have to give it a backstory, a weakness, maybe a tragic origin involving a cursed locket or a basement ritual gone wrong. In a short story? You don't have to explain anything. The monster is just there. And because the reader’s imagination is always more terrifying than anything a writer can describe, the lack of detail actually makes the story more effective.

The Power of the "Lurk"

Psychologists often point to the "threat-rehearsal theory" when explaining why we love horror. Basically, our brains use these stories as a safe way to practice for dangerous situations. When you read a story about someone hearing a scratching sound inside their drywall, your amygdala fires up. You’re scanning for exits. You’re thinking about what you would do.

Most people think the "jump scare" is the king of horror. They're wrong. The "lurk"—that slow-burn realization that something is wrong—is what actually sticks with you. It’s the difference between a loud noise and the sight of a hand slowly reaching out from under a couch in the background of a shot where the protagonist is just making a sandwich.

💡 You might also like: Kiss My Eyes and Lay Me to Sleep: The Dark Folklore of a Viral Lullaby

Why We Are Obsessed With Micro-Horror

The rise of the "creepypasta" changed everything. Before the internet, horror shorts were found in collections by Stephen King or Shirley Jackson. Now, they are communal. Stories like The Backrooms or Slender Man started as tiny snippets of text or a single doctored image. They grew because they felt like modern folklore.

- Pacing is everything. In a short piece, every word has to work. If a sentence isn't building tension or revealing a flaw, it's dead weight.

- The "Turn." Most viral horror shorts rely on a final sentence that recontextualizes everything you just read.

- Sensory Overload. Writers often focus too much on sight. The best stories talk about the smell of ozone before a ghost appears or the wet, slapping sound of bare feet on hardwood.

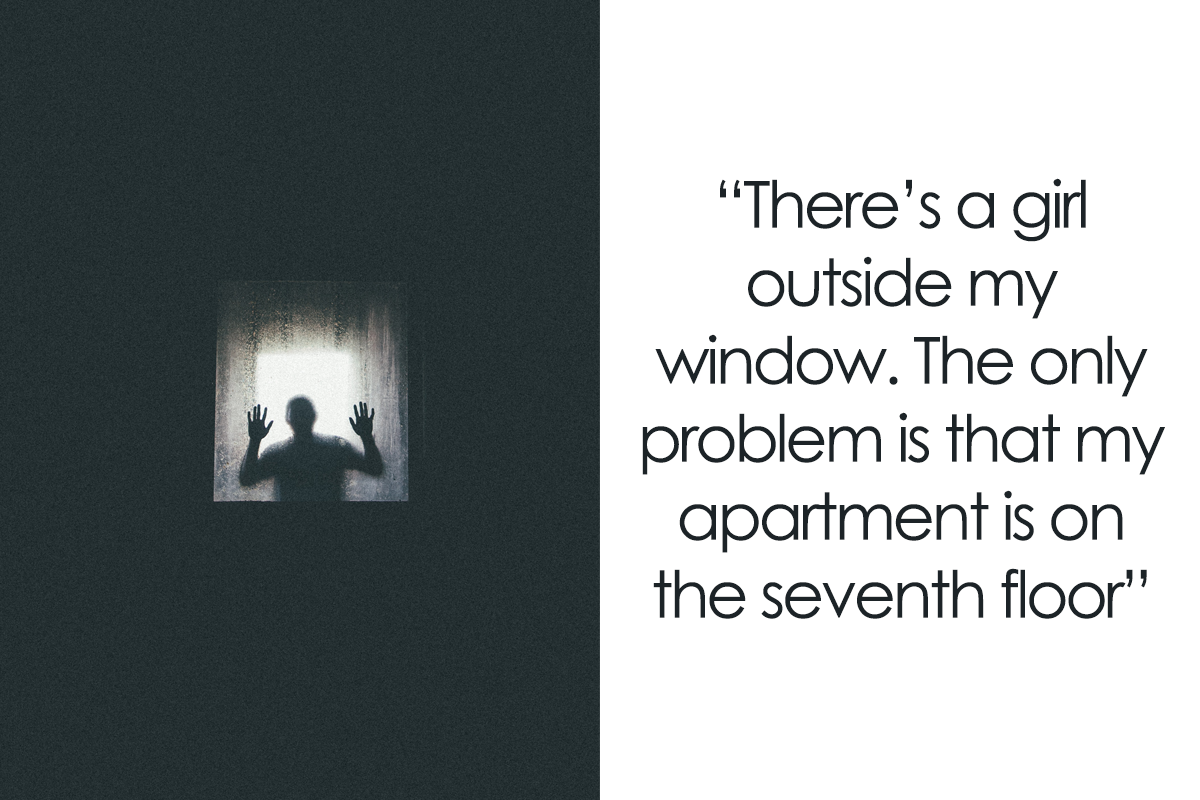

Honestly, the "Two-Sentence Horror" genre is the ultimate evolution of this. "My daughter won't stop crying and screaming in the middle of the night. I visit her grave and ask her to stop, but she never listens." It’s punchy. It’s dark. It uses your own assumptions against you.

Real Examples of Genre-Defining Shorts

You can't talk about this without mentioning "The Monkey's Paw" by W.W. Jacobs. It's the gold standard. It isn't scary because of a monster; it's scary because of the consequences of grief. When that knocking starts at the door at the end of the story, you don't see what's on the other side. You just know what the father knows: it's his son, but it's not his son.

Then you have "The Lottery" by Shirley Jackson. When it was first published in The New Yorker in 1948, people were so outraged and terrified they cancelled their subscriptions. Why? Because it suggested that the most horrific thing in the world isn't a demon or a ghost—it's your neighbors. It’s the mundane nature of the evil that makes it a legendary scary horror story short.

The Evolution of Digital Dread

We’ve moved past campfires. Now, the campfire is a glowing OLED screen in a dark bedroom at 2:00 AM. Digital horror uses the medium itself. We see stories told through "found footage" styles, or even "analog horror" videos on YouTube that mimic old emergency broadcast signals.

📖 Related: Kate Moss Family Guy: What Most People Get Wrong About That Cutaway

There’s a specific psychological trick called "tension and release." In a long movie, the director gives you "breather" scenes where characters joke around. In a short story, there is no release. The tension just ratchets up until the very last word, leaving you in a state of high arousal. Your heart rate is up, your pupils are dilated, and your brain is flooded with dopamine and adrenaline. It’s a literal drug hit.

Common Pitfalls in Short Horror

A lot of amateur writers think that "and then they died" is an ending. It’s not. It’s a stop. A real ending lingers.

- Too much gore. If I describe a crime scene for three paragraphs, I’m not scared; I’m bored and maybe a little nauseous.

- The "It was all a dream" trope. Don't do this. It’s the fastest way to make a reader feel like they wasted their time.

- Over-explaining. If the ghost is a Victorian girl who died in a fire, we've seen it a thousand times. If the ghost is a rhythmic thumping that only happens when you turn off the kitchen light, that’s new. That’s specific.

How to Consume Horror Without Losing Your Mind

If you're someone who loves a scary horror story short but struggles with the aftermath, there's actually a bit of science to "de-escalating" your brain. Because horror triggers the sympathetic nervous system (fight or flight), you need to manually trigger the parasympathetic nervous system to calm down.

Watch something "stupid" immediately after. Not just "not scary," but something fundamentally light—a sitcom you’ve seen a dozen times or a video of someone cleaning a rug. This signal tells your brain that the "threat" perceived in the story is over. It breaks the immersion.

Also, pay attention to the "safe distance." Reading a story is often scarier than watching a movie because your brain is doing the heavy lifting of rendering the images. If it gets too intense, change the medium. Switch to a podcast. Hearing a human voice tell the story can actually be more grounding than seeing a visual of a monster.

👉 See also: Blink-182 Mark Hoppus: What Most People Get Wrong About His 2026 Comeback

The Future of the Genre

We are seeing a move toward "liminal space" horror. These are stories set in empty malls, deserted office buildings, or endless hallways. It taps into a specific modern anxiety: the feeling of being somewhere you shouldn't be, or being somewhere familiar that is suddenly, inexplicably empty.

Artificial Intelligence is also starting to play a role, ironically. People are using AI to generate "uncanny" images that serve as prompts for short stories. The slight distortions—the extra fingers, the melting faces—perfectly capture that "uncanny" feeling we talked about earlier.

Finding the Best Stories

If you're looking for your next fix, don't just stick to the classics. The landscape is massive.

- Subreddits: r/nosleep is the big one, but r/shortscarystories is better for quick hits.

- Podcasts: The Magnus Archives starts as a series of short, disconnected horror "statements" before building a massive, interconnected world. Knifepoint Horror is also incredible for its stripped-down, narrator-focused approach.

- Anthologies: Look for the "Best Horror of the Year" collections edited by Ellen Datlow. She has an incredible eye for what makes a story truly unsettling.

The reality is that a scary horror story short works because it’s a controlled nightmare. We get to experience the absolute worst-case scenario from the safety of our blankets. It’s a paradox, sure, but it’s one that has defined human storytelling since we were huddling in caves.

The next time you’re scrolling through a thread of "true" ghost stories or picking up a new anthology, pay attention to your body. Watch how your breathing changes. Notice when you decide to turn on an extra light. That’s the power of the short form. It doesn't need a three-act structure to ruin your night; it just needs one perfectly placed image and a silence that lasts a second too long.

To get the most out of your horror reading, try "layering" your environment. Use ambient "dark academy" or "rainstorm" sounds on low volume. It fills the silence that usually makes people jumpy, but it maintains the mood. If you find a story that truly gets under your skin, write down exactly what triggered the fear. Was it the loss of control? The isolation? Understanding your own "fear profile" makes you a better critic and a more resilient reader. Stick to curated platforms like The Dark Magazine or Nightmare Magazine for professional-grade writing that avoids the cheap tropes of amateur creepypastas.