Ever tried to build a model of a tornado for a science fair or just because you’re a bit of a weather geek? Most people start with the classic "two soda bottles and a plastic connector" trick. You shake it, the water spins, and you get that satisfying little funnel. It’s cool. It looks like a tornado. But here is the thing: it’s actually not a tornado at all. Technically, that’s a whirlpool. A vortex? Yes. A model of atmospheric tornadogenesis? Not even close.

Real tornadoes are beasts of thermodynamics. They aren't just water spinning in a bottle; they are complex interactions of rising warm air, sinking cold air, and shifting wind directions. If you really want to understand how these monsters work, you have to look at how scientists simulate them, both in the lab and on massive supercomputers.

📖 Related: Samsung 65 Ultra HD 4k Smart TV: Why You Probably Don't Need the 8K Hype

The Problem with the "Bottle" Model of a Tornado

The soda bottle trick relies on gravity. Water pulls down, air moves up, and the spin happens because of the Coriolis effect or just how you swirled your wrist. In the real world, gravity isn't what makes a tornado spin.

Think about a supercell. That’s the "parent" thunderstorm. To create a legitimate model of a tornado, you need to simulate a "mesocyclone." This is a rotating updraft. In the atmosphere, this happens when wind speed and direction change as you go higher up. We call this wind shear.

Scientists like Dr. Leigh Orf at the University of Wisconsin-Madison don't use plastic bottles. They use some of the most powerful computers on the planet to build digital versions of these storms. When you see a high-resolution simulation of the 2011 El Reno tornado, you aren't just seeing a "funnel." You’re seeing millions of data points representing pressure, temperature, and moisture. That’s the real deal.

Building a Better Physical Model

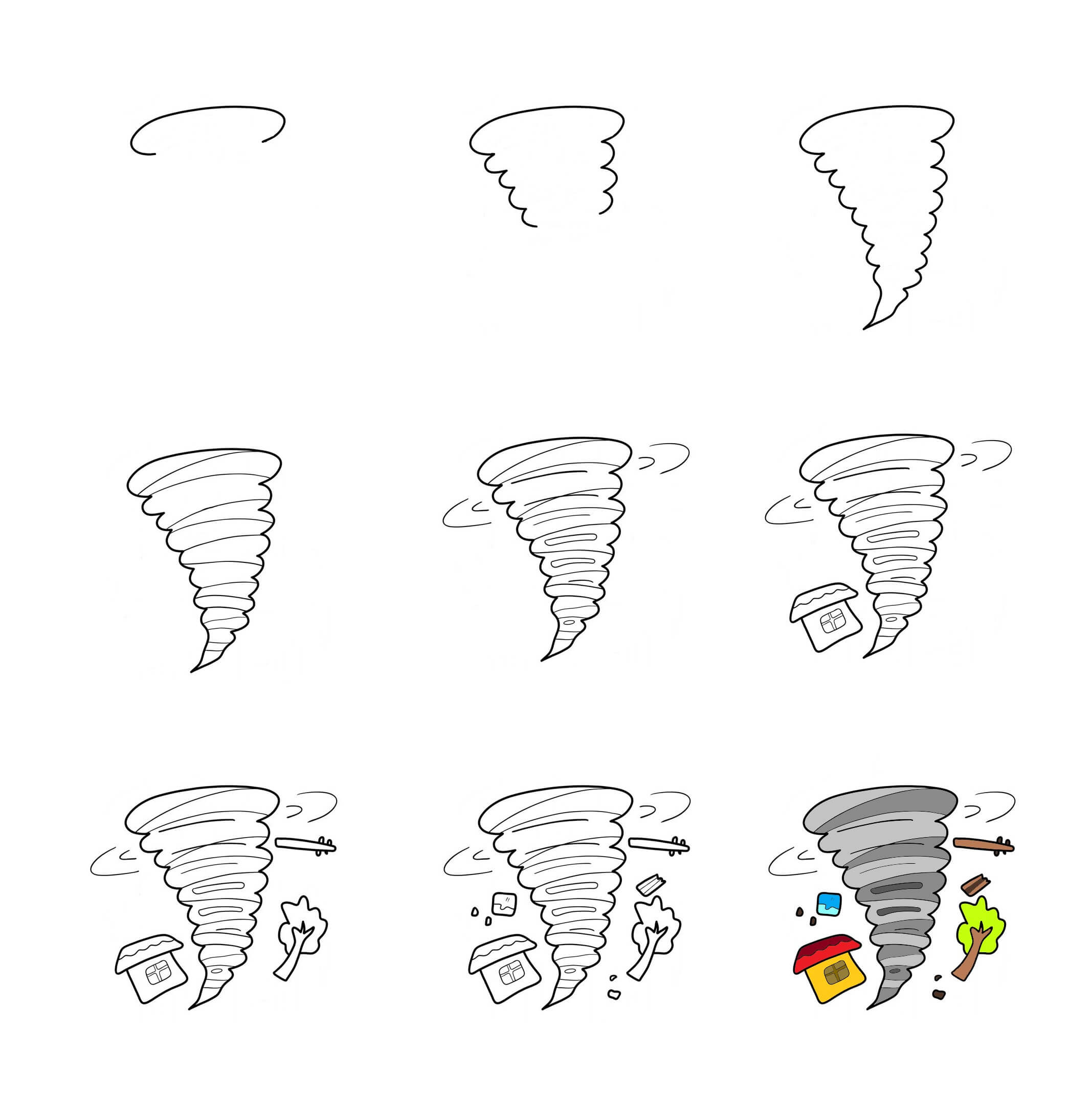

If you want to move past the bottle, you have to look at "tornado chambers." These are basically big boxes with a fan at the top.

The fan creates an updraft. That’s step one. But a fan alone just sucks air up. To get the spin, you need "vanes" or side-vents that blow air in at an angle. This creates the angular momentum. When the air reaches the center and gets sucked up by the fan, it tightens. It’s exactly like a figure skater pulling in their arms to spin faster. This is the conservation of angular momentum in action.

The George W. Bush Childhood Home in Midland, Texas, actually has a great example of a large-scale physical vortex generator. It’s a tall, open-sided chamber where mist is pumped in from the bottom. When the fans kick on, a ghostly, 10-foot-tall white funnel forms right in front of you.

- The Updraft: Controlled by the fan speed.

- The Inflow: This is where the air comes from.

- The Rotation: This is the most "fiddly" part to get right in a model.

Honestly, the hardest part of building a physical model of a tornado is the stability. If the room has a draft, the funnel wobbles and breaks. It’s fragile. Just like in nature, if the "inflow" of warm air gets cut off by a sudden gust of cold "outflow," the tornado dies.

The Numerical Model: Where the Real Science Happens

Physical models are neat for museums, but they can't tell us when a real storm is going to hit a town in Oklahoma. For that, we need numerical modeling.

The High-Resolution Rapid Refresh (HRRR) model is a workhorse for the National Weather Service. It’s a atmospheric model of a tornado environment that updates every single hour. It doesn't "see" the tornado itself—tornadoes are often too small for the "grid" of the model—but it sees the ingredients.

Imagine you're baking a cake. The model can tell you if you have the flour, eggs, and sugar in the bowl. It can tell you the oven is hot. But it might not be able to tell you exactly where the bubbles in the batter are forming.

Why Resolution Matters

In the early 2000s, models had a "grid spacing" of maybe 12 kilometers. That’s useless for a tornado that is only 500 yards wide. Today, researchers are pushing into the "sub-kilometer" range.

When you get down to 100-meter resolution, the math gets terrifying. You have to account for "friction" from trees and buildings. You have to account for "latent heat"—the energy released when water vapor turns into rain. It takes weeks of processing time to simulate just thirty minutes of a storm’s life.

Misconceptions That Ruin Your Model

People think the "eye" of a tornado is a vacuum. It’s not. It’s a low-pressure zone, sure, but it’s not sucking things up like a vacuum cleaner. It’s the wind that does the damage.

Another big mistake in any model of a tornado is ignoring the "debris ball." On radar, this is called a Tornado Debris Signature (TDS). When a model predicts a storm, meteorologists look for this "dual-pol" radar signature. It basically means the radar is bouncing off of pieces of houses and trees rather than raindrops.

- Pressure: It's low in the middle, but not a vacuum.

- Shape: They aren't always perfect cones. They can be "wedges" or "ropes."

- Multiple Vortices: Big tornadoes often have smaller "suction vortices" spinning around the main center. This is why one house gets leveled and the one next door is fine.

Practical Steps for Modeling or Observing

If you're looking to actually understand or build a model of a tornado, start with the "ingredients" method used by NOAA. Stop looking for the funnel and start looking for the environment.

- Step 1: Check the CAPE. This stands for Convective Available Potential Energy. It’s basically the fuel. If CAPE is over 2000 J/kg, the atmosphere is "loaded."

- Step 2: Look at the Helicity. This measures the "spin" in the lower atmosphere. High helicity means your model—or the sky—is ready to rotate.

- Step 3: Simulate the Outflow. If you are building a physical model, use a dry ice fogger or a high-output ultrasonic mister. The thicker the "tracer" (the mist), the easier it is to see the tight rotation near the floor.

If you are a student or a hobbyist, don't just buy a kit. Experiment with the "aspect ratio" of your chamber. If you make the chamber too wide, the funnel becomes a "multi-vortex" mess. If it's too narrow, it stays a "rope."

Most importantly, look at the VORTEX2 project data. This was a massive field study where scientists literally surrounded tornadoes with mobile radars. Their data shows that what happens under the cloud base—the bottom 100 feet—is what actually determines if a tornado stays on the ground or lifts. That’s the "boundary layer," and it’s the most difficult thing to replicate in any model of a tornado.

To get a better sense of how the professionals do it, go to the National Severe Storms Laboratory (NSSL) website and look at their "Warn-on-Forecast" research. They are trying to move from "detecting" a tornado that already exists to "predicting" one before it even forms. It’s all based on the very models we’ve been talking about. Start by tracking the Significant Tornado Parameter (STP) on sites like College of DuPage Weather—it’s a "model of models" that simplifies the complex math into a single number.