Look at any standard classroom poster and you’ll see it. A jagged line running down the center of the Atlantic Ocean like a giant, underwater scar. Most people think of the Mid Atlantic Ridge diagram as a simple divider, a place where the earth just... opens up. But honestly? It’s way more chaotic than those clean lines suggest. We’re talking about a 10,000-mile mountain range that is literally the spine of the planet, and it’s doing things right now that defy the "slow and steady" logic we were taught in grade school.

The Atlantic is growing. Every single year, North America and Europe move about 2.5 centimeters further apart. That’s roughly the speed your fingernails grow. It sounds pathetic, really. But when you multiply that by millions of years, you get an entire ocean basin. If you’re looking at a Mid Atlantic Ridge diagram, you’re actually looking at a massive volcanic construction site that never closes.

What a Realistic Mid Atlantic Ridge Diagram Actually Shows

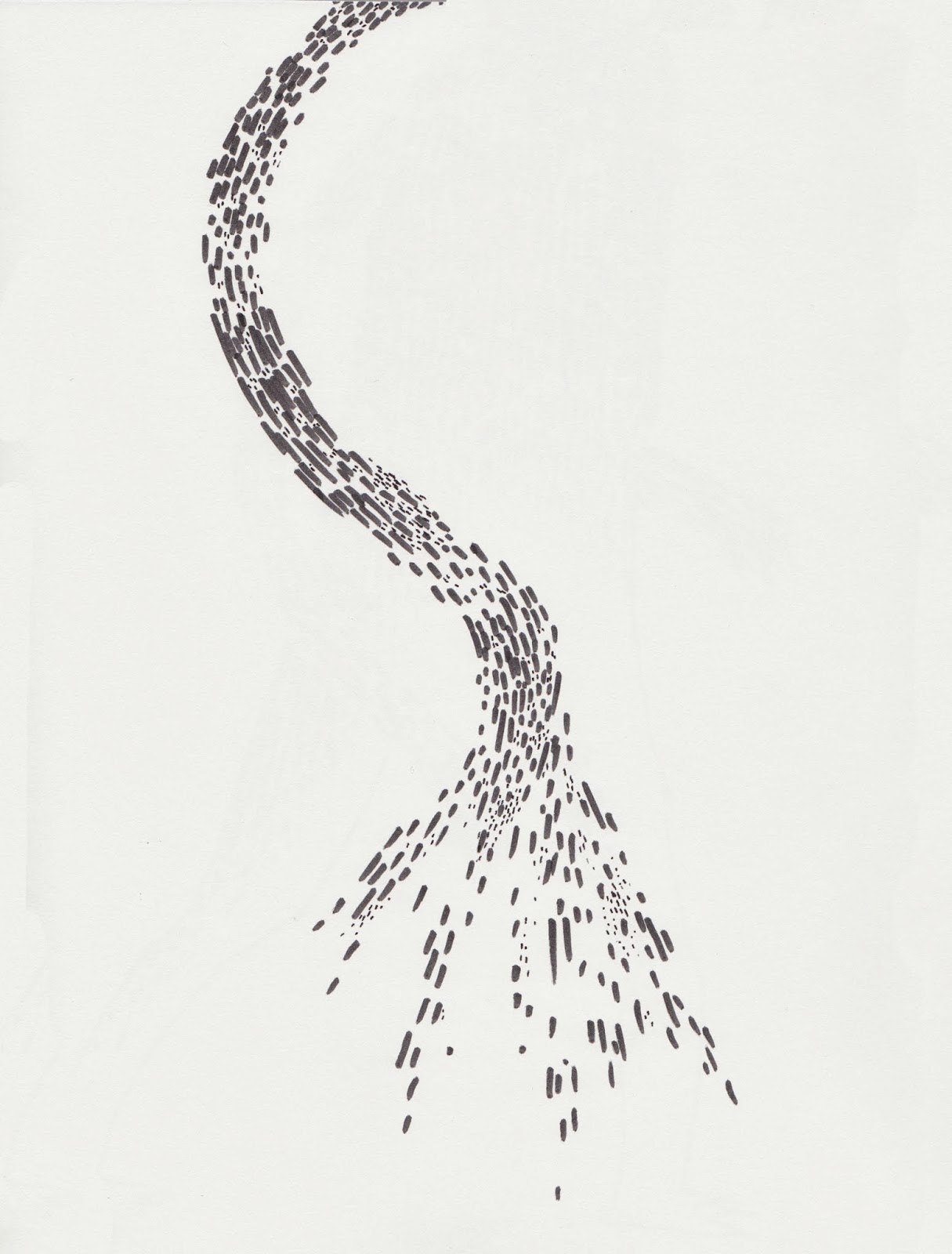

If you find a good, high-resolution map, you’ll notice the ridge isn’t a straight line. It’s broken. It looks like a zipper that got caught in the wash. These breaks are transform faults. They happen because the Earth is a sphere, not a flat map, and trying to pull apart a curved surface means things snap and slide sideways.

Most diagrams highlight the Rift Valley. This is the "V" shape at the very top of the ridge. It’s deep. In some places, the valley floor drops six to nine thousand feet below the surrounding mountain peaks. It’s a place of constant earthquakes. Most of them are too small for us to feel on land, but if you were a fish living down there, your world would be shaking pretty much non-stop.

The Magma Problem

Wait, where does the new land come from? It’s not like there’s a giant vat of liquid lava just sitting there waiting to pop out. It’s a bit more subtle. As the plates pull apart, the pressure on the mantle underneath drops. This "decompression melting" turns solid rock into slushy magma. It rises, hits the freezing seawater, and hardens into basalt. This is the crustal factory.

Why Iceland Is the Ridge's Weirdest Exception

Usually, the Mid Atlantic Ridge is buried under miles of dark, crushing water. But then there’s Iceland. Iceland is basically the ridge decided to come up for air.

👉 See also: Ethics in the News: What Most People Get Wrong

It’s one of the few places on Earth where you can stand in a Mid Atlantic Ridge diagram in real life. At Þingvellir National Park, you can literally walk between the North American and Eurasian plates. It’s a massive canyon of black rock. Most geologists call Iceland a "hotspot" that happens to sit right on top of the ridge. The extra boost of magma from deep in the Earth pushed the ridge high enough to break the surface.

Without Iceland, our understanding of the ridge would be purely based on sonar and expensive robot subs. Iceland gives us a front-row seat to the plumbing of the planet. You can see the fissures opening. You can smell the sulfur. It’s raw geography.

The Life Nobody Expected Down There

For a long time, we thought the deep ocean was a desert. Cold, dark, and dead. Then, researchers started looking closer at the ridge. They found hydrothermal vents, often called "black smokers."

These aren't just holes in the ground. They are towering chimneys of minerals. They pump out water that is hot enough to melt lead—upwards of 400°C ($752°F$). You’d think anything nearby would be instantly cooked, right? Instead, these vents are swarming with life.

- Ghost-white shrimp that lack eyes because there’s zero light to see anyway.

- Giant tube worms that live off bacteria.

- Extremophiles that eat chemicals instead of using sunlight.

This process is called chemosynthesis. It’s the opposite of how plants work. It’s so alien that NASA uses the Mid Atlantic Ridge as a testing ground to figure out how life might survive on moons like Europa or Enceladus. If you see a diagram of the ridge that doesn't include these vent systems, it’s missing the most interesting biological story on Earth.

✨ Don't miss: When is the Next Hurricane Coming 2024: What Most People Get Wrong

Misconceptions That Mess With Your Head

People often ask: "If the Atlantic is getting bigger, is the Earth inflating like a balloon?"

Nope.

While the Mid Atlantic Ridge is making new floor, other parts of the world—like the "Ring of Fire" in the Pacific—are eating it. It's called subduction. The Atlantic is the "growth" side of the equation. The Pacific is the "recycling" side.

Another big mistake? Thinking the ridge is just one long volcano. It's actually thousands of individual volcanic centers. Some are active, some are dormant, and some are just leaking heat. It’s a patchwork.

The Magnetic Tape Recorder

This is the part that usually blows people's minds. The Earth's magnetic field isn't permanent. Every few hundred thousand years, North and South swap places. When the magma at the Mid Atlantic Ridge cools, the iron minerals inside align with the current magnetic field. They freeze in place.

🔗 Read more: What Really Happened With Trump Revoking Mayorkas Secret Service Protection

This creates "magnetic stripes" on the ocean floor.

When scientists first mapped these stripes in the 1960s, it was the "smoking gun" for plate tectonics. The stripes are perfectly symmetrical on both sides of the ridge. It proved the floor was moving away from the center. It’s like a giant tape recorder that has been logging Earth’s magnetic history for 200 million years.

Getting Technical: Slow vs. Fast Spreading

Not all ridges are built the same. The Mid Atlantic Ridge is a "slow-spreading" ridge. Because it moves so slowly, it has that deep, well-defined central rift valley we talked about. Fast-spreading ridges, like the East Pacific Rise, move much quicker—up to 15 centimeters a year. Those ridges don't have deep valleys; they look more like smooth, bloated domes because the magma is supplied so fast the ground doesn't have time to collapse into a rift.

Actionable Insights for Your Research

If you’re trying to use a Mid Atlantic Ridge diagram for a project, or you're just a geology nerd, don't stop at the surface-level stuff.

- Check the Bathymetry: Use tools like Google Earth (with the ocean layer on) to see the actual texture of the ridge. Notice how the transform faults (those horizontal lines) are actually more prominent than the vertical ridge itself in some areas.

- Follow the Earthquakes: Visit the USGS (United States Geological Survey) real-time earthquake map. Filter for the Atlantic Ocean. You will see a near-perfect dots-to-dots recreation of the ridge based solely on where the ground is currently snapping.

- Explore the Vents: Look up the "Lost City" hydrothermal field. It’s a specific spot on the ridge where the vents are made of white carbonate instead of black sulfides. It looks like an underwater castle and changed what we thought was possible for deep-sea chemistry.

- Look at the Age: Find a map of "Seafloor Age." You’ll see the rock at the ridge is brand new (red), while the rock hitting the coast of New York or West Africa is nearly 200 million years old (blue/purple).

The Mid Atlantic Ridge isn't just a line on a map. It’s the reason the continents look the way they do today. It’s a massive, slow-motion engine that is still reshaping the world while you sleep. Next time you see a diagram of it, remember you're looking at the literal birth of the Earth's crust.

Next Steps for Deep Exploration:

To truly grasp the scale, your next move should be investigating the Romanche Fracture Zone. It is one of the deepest "breaks" in the Mid Atlantic Ridge near the equator, where the ridge is offset by over 600 miles. Studying this specific area shows exactly how much strain the Earth is under as it tears itself apart. You can also track the Surtsey Island eruption records to see how a brand-new piece of the ridge can create a whole new island in just a few days.