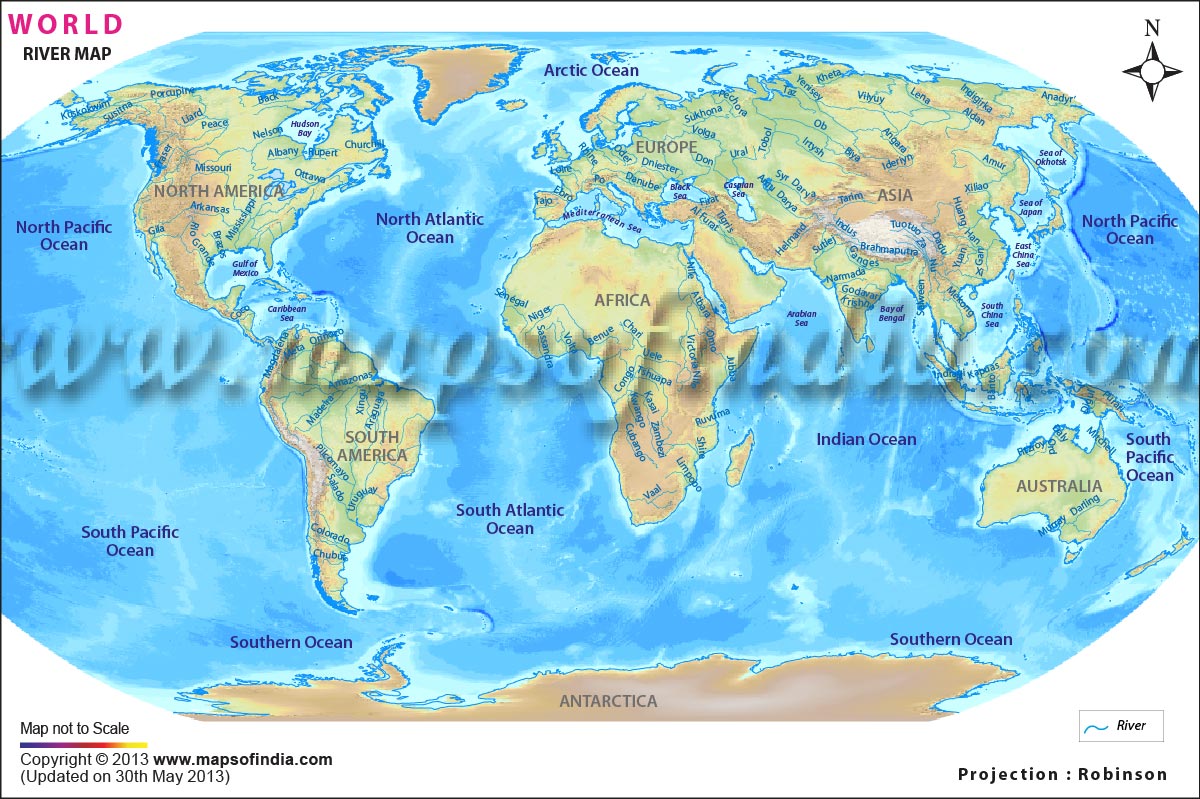

Water moves. It’s that simple. But if you look at a standard map of world rivers, you’re usually seeing a static, blue-lined lie that doesn't actually show how the planet breathes. Most of us grew up looking at those school posters where the Amazon is a thick vein and the Nile is a long, lonely string. Honestly, it’s way more chaotic than that.

Rivers are messy. They braid, they dry up, they shift course over a single weekend, and they occasionally flow backward. When you start digging into the actual cartography of global drainage basins, you realize that our "standard" maps prioritize political borders over the actual physical plumbing of the Earth. We see a line on a page and think "river," but we should be thinking "pulse."

The Amazon vs. The Nile: The Grudge Match That Won't Die

For decades, every textbook told you the Nile was the longest river. Period. Case closed. But if you talk to modern geographers or check out updated digital mapping projects like those from the Brazilian National Institute for Space Research (INPE), things get murky. Some researchers argue that the Amazon actually starts much further south in the Peruvian Andes than previously thought. If that’s true—and the data from a 2007 expedition suggests it might be—the Amazon clocks in at roughly 6,992 kilometers, beating the Nile's 6,853 kilometers.

It’s not just a pissing contest for explorers. It changes how we map biodiversity. The Amazon isn't just a river; it's a hydrological engine. It pumps so much freshwater into the Atlantic that it actually lowers the salinity of the ocean for hundreds of miles. You can be out of sight of land and still be sailing in "river" water. That’s the kind of scale a flat map of world rivers usually fails to convey.

Then you have the Nile. It’s the ultimate survivor. It flows through the Sahara, losing massive amounts of water to evaporation every single mile, yet it still reaches the Mediterranean. Most maps show it as a solid blue line, but in reality, it’s a managed, dammed, and heavily contested liquid lifeline. From the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam (GERD) to the Aswan High Dam, the "map" of the Nile today is as much about concrete and geopolitics as it is about water.

Why Drainage Basins Matter More Than Lines

If you really want to understand the planet, stop looking at the lines and start looking at the "blobs." These are drainage basins. A map of world rivers that highlights basins shows you where every single drop of rain eventually ends up.

Take the Mississippi-Missouri system. On a basic map, it looks like a big tree. But its basin covers about 40% of the continental United States. If someone spills a chemical in Montana, it has a direct, mapped path to the Gulf of Mexico. This is why maps used by the World Resources Institute (WRI) look so different from the ones in your old atlas; they focus on "Aqueduct" data, showing water stress and flow volume rather than just length.

📖 Related: Ilum Experience Home: What Most People Get Wrong About Staying in Palermo Hollywood

The Ghost Rivers of the Sahara and Australia

Ever heard of the Lake Eyre Basin? It’s one of the largest endorheic systems in the world. Basically, the water flows inward to a big salty sink instead of the ocean. Most of the time, the "rivers" on this map are bone dry. They’re just tracks in the sand. But when the rains hit once every decade or so, the map transforms.

- The Cooper Creek becomes a massive, miles-wide flood.

- The Diamantina River starts moving fish across a desert.

- Birds appear out of nowhere.

This is the problem with static mapping. We map the potential for a river, not the reality of it. In Northern Africa, the "Trans-Saharan River System" is a ghost. Thousands of years ago, a river the size of the Rhine flowed through what is now the desert. We can see it in radar imagery from satellites, buried under the dunes. It’s a reminder that our current map of world rivers is just a snapshot in geological time. It’s temporary.

The Vertical Map: Rivers You Can’t See

We need to talk about "Flying Rivers." This sounds like some sci-fi nonsense, but it’s a critical part of how water moves across South America. The Amazon rainforest transpires billions of tons of water vapor into the atmosphere. This moisture travels like a massive river in the sky, blocked by the Andes mountains and forced to fall as rain in places like São Paulo.

If you clear-cut the forest, the flying river stops. The map of world rivers on the ground dries up because the map in the air was destroyed. Cartographers are now trying to find ways to layer this atmospheric data onto traditional maps because, frankly, you can't understand the Rio de la Plata without understanding the vapor coming off the jungle a thousand miles away.

The Weirdness of Endorheic Basins

Most people assume all rivers go to the sea. They don't. About 18% of the Earth's land drains into endorheic basins—dead ends.

- The Caspian Sea: It’s basically a giant lake fed by the Volga. The Volga is the longest river in Europe, yet it never touches the ocean.

- The Okavango Delta: This is a river that flows into a desert and just... disappears. It creates an oasis and then evaporates or seeps into the Kalahari sands.

- The Jordan River: It ends in the Dead Sea, which is so low and so salty that nothing lives there.

When you look at a map of world rivers, these "dead ends" are often some of the most ecologically sensitive spots on the map. They are also the first to disappear when we over-extract water for farming. The Aral Sea is the poster child for this. Once fed by the Amu Darya and Syr Darya, it’s now mostly a toxic dust bowl because we changed the map to grow cotton.

👉 See also: Anderson California Explained: Why This Shasta County Hub is More Than a Pit Stop

Digital Mapping and the "Global River Width" Revolution

So, how do we actually map this stuff accurately now? We use things like the GRWL (Global River Width from Landsat) database. Researchers like George Allen and Tamlin Pavelsky used thousands of satellite images to measure the actual surface area of the world's rivers.

They found that rivers cover about 45% more area than we previously estimated. This isn't because the rivers grew; it's because our old maps were just bad. We were missing the small stuff. We were missing the way rivers widen and contract. This data is huge for climate change modeling because the surface area of a river determines how much carbon dioxide it releases into the atmosphere.

The Geopolitics of the Blue Line

Rivers don't care about countries. The Brahmaputra starts in China (as the Yarlung Tsangpo), flows through India, and ends in Bangladesh. Each country maps it differently. China sees it as a source of hydroelectric power. India sees it as a sacred lifeblood and a potential flood threat. Bangladesh sees it as the thing that keeps their soil fertile but also threatens to drown the nation as sea levels rise.

When you look at a map of world rivers in a political context, you're looking at a fuse. There are over 260 transboundary river basins globally. Conflicts over the Mekong, the Indus, and the Tigris-Euphrates are literally redrawing the "power map" of the 21st century.

Actionable Ways to Use River Maps Today

If you’re a traveler, an educator, or just a nerd for geography, don’t settle for the blue squiggles on a standard globe.

Use Interactive Basins: Check out tools like "River Runner." You can click any point on a map of the US (and some global versions), and it will animate the path a drop of water takes from that spot to the ocean. It’s a mind-blowing way to see how interconnected the world is.

✨ Don't miss: Flights to Chicago O'Hare: What Most People Get Wrong

Look at "Near-Real-Time" Flow: NASA’s Earth Observatory and the USGS provide satellite-based flow data. If you’re planning a trip to the Amazon or the Danube, you can see if the river is actually "there" in the volume you expect, or if it’s currently a trickle due to drought.

Support OpenStreetMap (OSM): Most commercial maps (like Google) are great for roads but "okay" for rivers. The OSM community manually traces high-res imagery to map small tributaries that big companies ignore. If you live near a creek that isn't on the map, you can actually put it there.

Think in 3D: Rivers are the sculptors of the landscape. Use Google Earth’s 3D view to follow the Colorado River through the Grand Canyon. You’ll see that the "map" isn't just a line; it's a deep, jagged scar that took millions of years to carve.

The map of world rivers is a living document. It’s changing as glaciers melt in the Himalayas and as we build more dams in the Balkans. Stop treating the atlas like it's written in stone. It’s written in water, which means it’s being rewritten every single day.

To get a better handle on this, start by looking up your local watershed. Find out where your tap water comes from and where your gutter water goes. Once you see the "veins" in your own backyard, the giant "arteries" like the Yangtze or the Congo start to make a whole lot more sense. You realize that we don't just live near rivers; we live on them. Every piece of dry land is just a space between the flows.