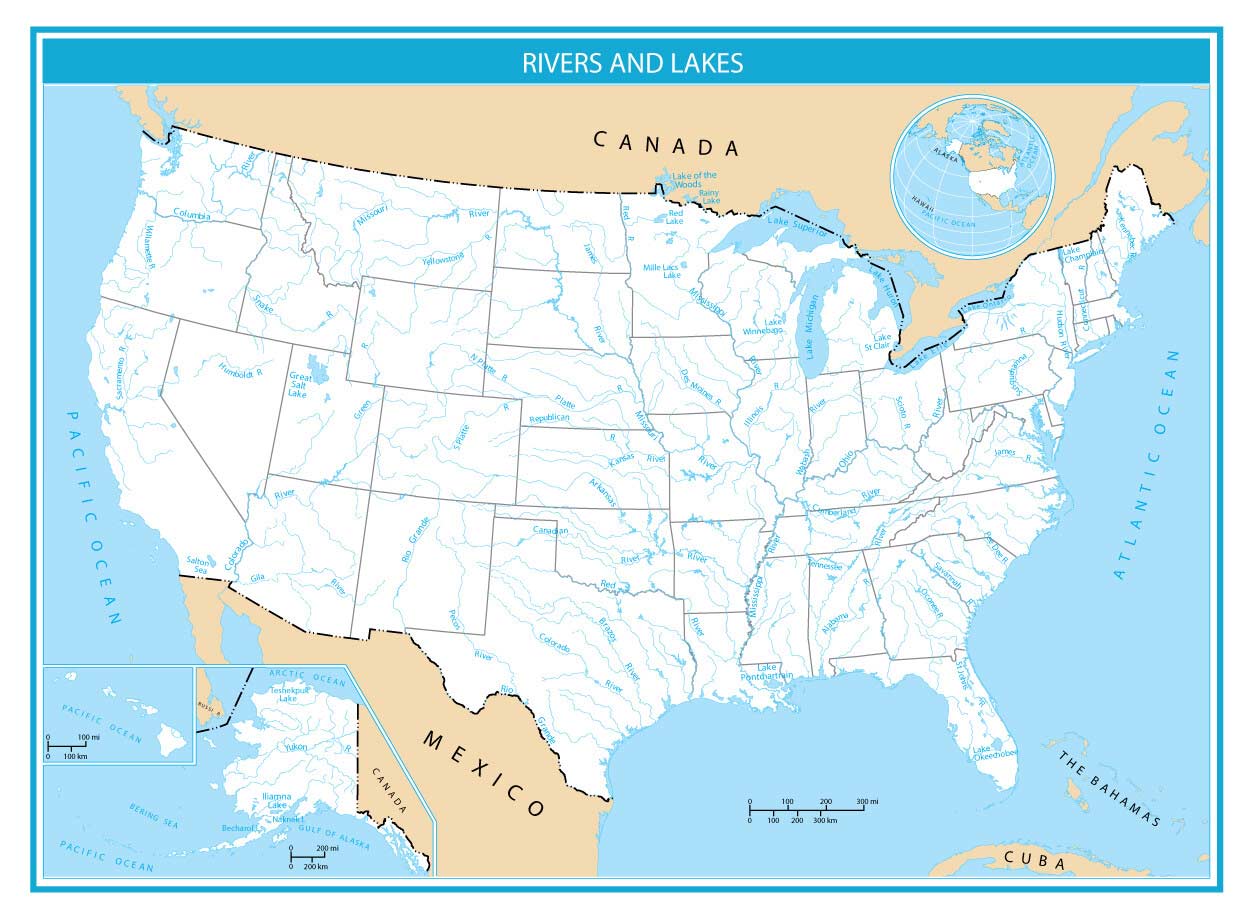

Look at a standard map of United States rivers and mountains and you’ll probably see a messy tangle of blue veins and brown bumps. It looks static. Permanent. But if you actually spend time in the backcountry or talk to a geomorphologist, you realize these lines on the page are basically a snapshot of a massive, ongoing brawl between tectonic plates and the relentless pull of gravity.

Geography isn't just about where things are. It’s about why they are there.

Most people can point out the Rockies or the Mississippi. That’s easy. But do you know why the New River in the Appalachians is actually one of the oldest rivers in the world, despite its name? Or why the Great Basin in Nevada is essentially a giant topographical sink where water goes to die? When you start digging into the actual physical layout of the Lower 48, the "purple mountain majesties" bit starts to feel a lot more like a violent, beautiful history lesson written in rock and silt.

The Great Divide and the Spine of a Continent

The Continental Divide is the ultimate "choose your own adventure" for a raindrop. If a storm hits the crest of the Rockies, one drop might end up in the Gulf of Mexico, while its neighbor flows toward the Pacific. It's a literal line in the sand—or granite—that dictates the entire hydrography of the West.

The Rocky Mountains aren't just one big wall. They’re a collection of more than 100 separate ranges stretching from Canada down into New Mexico. You’ve got the Front Range in Colorado, the Tetons in Wyoming, and the Bitterroots in Montana. They are young. High. Jagged. Because they haven't been worn down by time yet, they act as a massive "rain shadow" creator. This is why you can have a lush forest on one side of a ridge and a literal desert five miles away on the other.

Compare that to the Appalachians.

✨ Don't miss: Anderson California Explained: Why This Shasta County Hub is More Than a Pit Stop

These mountains are old. Like, "older than the Atlantic Ocean" old. They used to be as tall as the Himalayas, but hundreds of millions of years of rain and wind have sanded them down into the rolling, green ridges we see today. When you look at an Appalachian map of United States rivers and mountains, you see something weird. The rivers there, like the Susquehanna and the James, often cut right through the mountain ridges instead of flowing around them. This is called "antecedent drainage." The rivers were there first. As the mountains slowly pushed up, the rivers just kept cutting their paths, like a saw through a rising log.

Water Always Wins: The Heavy Hitters

The Mississippi River is the undisputed heavyweight champion of American waterways. It drains about 40% of the continental United States. If you look at the drainage map, it looks like a giant tree with its roots in the Gulf of Mexico and its branches reaching out to the Rockies in the west and the Appalachians in the east.

But it’s not just one river.

The Missouri River is actually longer. If you measure from the headwaters of the Missouri in Montana down to the Gulf, you’re looking at over 3,700 miles. We call it the Mississippi-Missouri system, and it’s the lifeblood of the American heartland. It carries massive amounts of sediment—basically the ground-up remains of the Rocky Mountains—down to Louisiana to build the delta.

Then you have the "weird" rivers.

🔗 Read more: Flights to Chicago O'Hare: What Most People Get Wrong

- The Colorado River: This is the one that carved the Grand Canyon. It’s a workhorse, providing water to nearly 40 million people, but it rarely reaches the sea anymore because we’ve tapped it so heavily for cities like Las Vegas and Phoenix.

- The Rio Grande: It’s a political border, sure, but geologically it’s a rift valley. The earth is literally pulling apart there.

- The Columbia River: This thing is a powerhouse. It has more flow than any other North American river entering the Pacific. It’s the reason the Pacific Northwest has such cheap hydroelectric power.

The Great Basin: Where the Map Stops Making Sense

Most maps show rivers flowing to the ocean. That’s the rule, right? Well, Nevada and parts of Utah, California, and Oregon didn't get the memo.

This area is called the Great Basin.

It’s a massive "hydrographic endorheic" region. Basically, it’s a bowl. Any rain that falls here stays here. It flows into salty lakes like the Great Salt Lake or just evaporates into the desert air. The Humboldt River in Nevada is a prime example. It starts in the mountains, flows across the state, and then just... ends. It vanishes into the Humboldt Sink.

Geologically, this area is "Basin and Range" country. Think of it like a series of tilted blocks of earth. You have a mountain, a flat valley, a mountain, a flat valley. It’s one of the most unique landscapes on Earth, and it’s why driving across Nevada feels like a never-ending rollercoaster of high passes and sagebrush flats.

Why the "Blue Lines" and "Brown Bumps" Matter Now

Understanding a map of United States rivers and mountains isn't just for trivia night. It's about resources. In the 21st century, the "100th Meridian" has become a huge topic of conversation. This is the invisible line that roughly divides the humid eastern U.S. from the arid West.

💡 You might also like: Something is wrong with my world map: Why the Earth looks so weird on paper

Historically, everything west of that line (roughly through the middle of the Dakotas down through Texas) has struggled with water. As the climate shifts, the snowpack in the mountains—which acts as a giant natural water tower—is melting earlier. This affects the rivers. If the Rockies don't hold onto that snow, the Colorado and Missouri rivers don't have enough water for the summer heat.

We’re also seeing "relict" landscapes changing. In the East, the aging Appalachians are seeing more "thousand-year" flood events because the narrow valleys can't handle the intensity of modern storms. The mountains haven't changed, but the way water interacts with them has.

How to Actually Use This Info

If you're planning a cross-country trip or just want to understand the terrain better, stop looking at the interstate map. Switch to a topographic layer.

- Follow a single watershed. Pick a river like the Ohio or the Arkansas. Track it back to its source in the mountains. You'll see how the topography dictates every town, farm, and road along the way.

- Look for the "Gap" towns. Notice how cities like Cumberland, Maryland, or El Paso, Texas, exist specifically because there’s a break in the mountains. Humans always take the path of least resistance, which is usually a river valley.

- Check the Continental Divide. If you’re ever in Glacier National Park or Yellowstone, find the signs for the divide. It’s a trippy feeling to stand there knowing that a cup of water poured out will end up thousands of miles away from a cup poured out just ten feet to your left.

The American landscape is a messy, violent, and constantly shifting puzzle. The mountains are rising or crumbling, and the rivers are either building land or tearing it away. A map is just a temporary status report on that struggle.

To get a real sense of the scale, use the USGS (United States Geological Survey) National Map viewer. It allows you to toggle between hydrography (water) and orography (mountains) with insane detail. You can see how the Ozark Plateau in Missouri is actually a dissected plateau, not a "mountain range" in the traditional sense, or how the Central Valley in California is basically a giant bathtub caught between the Coast Ranges and the Sierra Nevada.

Understanding these physical barriers explains everything from why the Civil War was fought the way it was to why your grocery bills for produce fluctuate based on California’s snowpack. It’s all connected by the slope of the land and the path of the water.