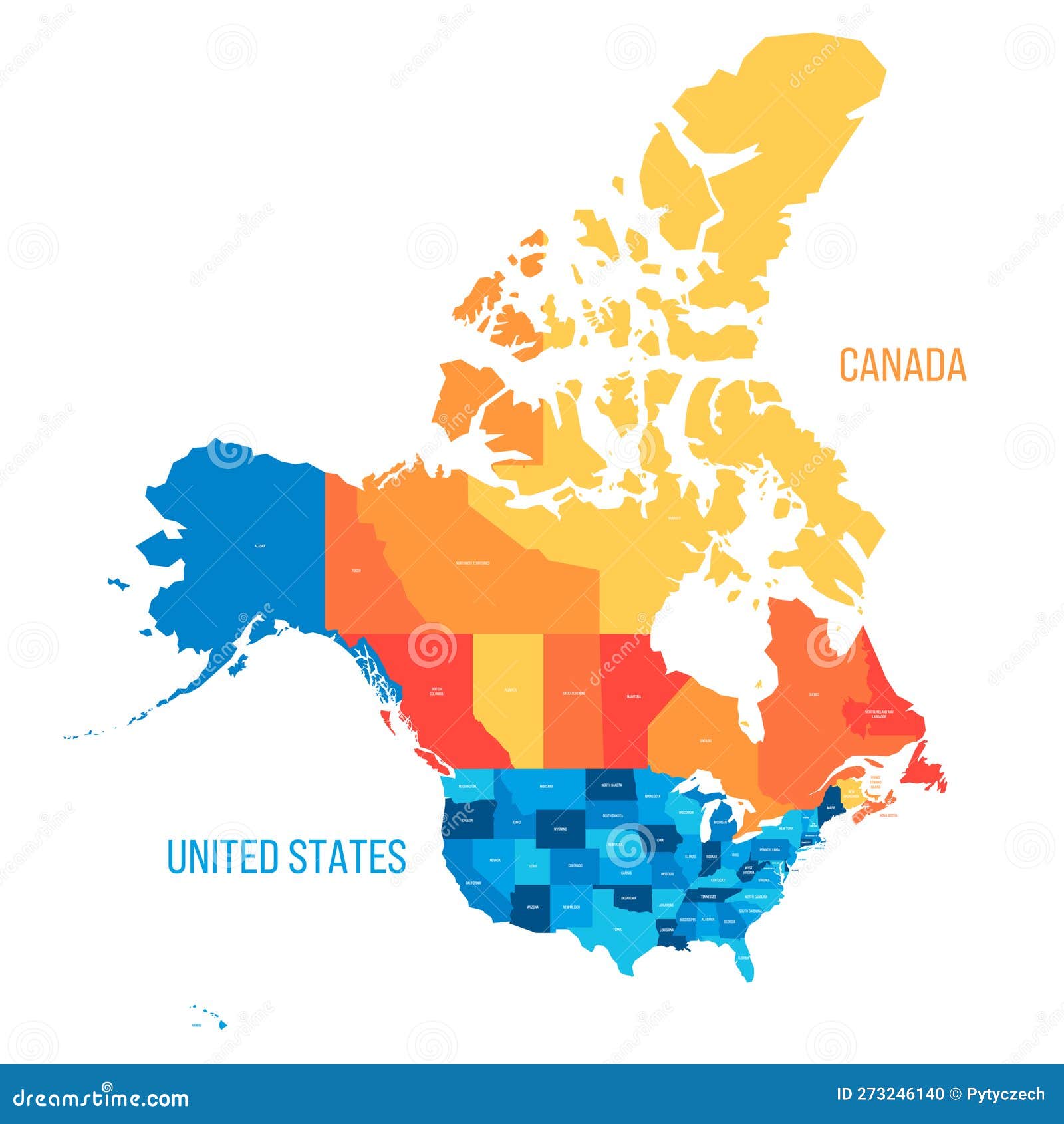

Look at it. Just really look at it. If you pull up a standard map of United States Canada and Alaska on your phone or a wall poster, you’re looking at a massive, unintentional lie. It’s the Mercator projection’s fault. This 16th-century navigational tool stretches the poles so much that Greenland looks like the size of Africa, and Alaska looks like it could swallow the entire Lower 48 states for breakfast.

It can't. Not even close.

But size isn't the only thing we get wrong. When we talk about this specific North American trio, we’re looking at one of the most complex geographical puzzles on Earth. You have the "Mainland" US, the massive Canadian wilderness, and then Alaska—the weird, icy cousin hanging off the side of Canada like a backpack it forgot to take off. Honestly, trying to visualize how these three entities actually fit together is a lesson in geopolitical awkwardness.

Most people don't realize that if you drove from Seattle to Juneau, you'd spend more time in a different country than your own. That’s the reality of the North American landscape.

The Alaska Gap: A Geopolitical Headache

The biggest misconception people have when looking at a map of United States Canada and Alaska is the distance. Because Alaska is often tucked into a tiny little box in the bottom left corner of US maps—right next to Hawaii—we lose all sense of scale.

Alaska is huge. It’s roughly 663,000 square miles.

If you cut Alaska in half, Texas would become the third-largest state. Think about that for a second. Yet, on a map, it looks like this isolated island. In reality, it shares a 1,538-mile border with Canada. This isn't just a line in the dirt; it's a massive stretch of tundra, mountains, and the Yukon River that creates a strange logistical nightmare for anyone trying to move goods between the US mainland and the 49th state.

Ever heard of the Northwest Angle? It’s this tiny chimney of land in Minnesota that actually sticks up into Canada. It’s the only place in the contiguous US north of the 49th parallel. Why does this matter? Because when you look at the broad sweep of the Canadian border, you realize it isn't a straight line. It’s a jagged, historically messy boundary that reflects years of British and American bickering.

Then you have the AlCan Highway.

The Alaska-Canadian Highway is the literal thread sewing these three regions together. Built during World War II out of a sheer panic that the Japanese might invade the West Coast, it cuts through 1,300 miles of Canadian wilderness to connect Dawson Creek, British Columbia, to Delta Junction, Alaska. If you’re looking at a map and planning a road trip, you aren't just crossing a border; you’re entering a zone where the map becomes your only friend because cell service dies the second you leave the paved roads.

💡 You might also like: Leonardo da Vinci Grave: The Messy Truth About Where the Genius Really Lies

Why Canada is "Lower" Than You Think

We always think of Canada as "The Great White North." We imagine it sitting entirely above the United States.

Wrong.

Look closely at the map of United States Canada and Alaska near the Great Lakes. You’ll notice that a huge chunk of Ontario actually dips south of the northern borders of California and Nevada. In fact, about 50% of Canadians live south of the 45th parallel. That puts them roughly on the same latitude as Portland, Oregon, or even parts of northern Italy.

The map reveals a "population hug."

Almost the entire Canadian population is huddled within 100 miles of the US border. When you zoom out, the map shows this massive, empty expanse of the Canadian Shield—ancient rock and forest—that acts as a giant buffer between the bustling US-Canada border and the Arctic wildness of the North.

The Problem With Projections

Let's get nerdy for a second. Most maps use the Mercator projection. It was great for sailors in the 1500s because it kept lines of constant bearing straight. But it's terrible for showing the true size of landmasses.

On a Mercator map:

- Alaska looks as big as the entire continental US.

- Canada looks like it occupies 25% of the world’s land.

- The United States looks relatively small.

If you switch to a Gall-Peters or a Robinson projection, the map of United States Canada and Alaska shifts. Suddenly, Africa balloons to its rightful, massive size, and the northern regions "shrink" to their actual proportions. Canada is still the second-largest country on Earth, but it’s not the infinite continent-swallowing monster that your grade school map suggested.

The Bering Strait and the Russian Neighbor

The map doesn't just show three entities; it shows a bridge to another world.

📖 Related: Johnny's Reef on City Island: What People Get Wrong About the Bronx’s Iconic Seafood Spot

When you look at the far western edge of Alaska, you see the Seward Peninsula. Just 55 miles across the water is Russia. People often joke about "seeing Russia from my house," but in the middle of the Bering Strait sit two islands: Big Diomede (Russia) and Little Diomede (USA).

They are only about 2.4 miles apart.

Walking between them in the winter is technically possible if the ice is thick enough, though it's highly illegal and you’d be crossing the International Date Line. You’d literally be walking into tomorrow. This narrow gap on the map is one of the most strategically significant spots on the planet, especially as Arctic ice melts and new shipping lanes open up.

Logistics of the North: The Panhandle Issue

One of the most visually striking parts of the map of United States Canada and Alaska is the Alaska Panhandle. It’s that long strip of islands and coastline that runs down the side of British Columbia.

It looks like Canada got cheated.

Historically, this was the result of the Alaska Boundary Dispute. The British (representing Canada) and the Americans fought over where the line should be drawn. The US wanted the coast; Canada wanted deep-water access for the Klondike gold fields. In 1903, a tribunal ruled mostly in favor of the US.

The result?

A map where Canada is effectively "blocked" from the Pacific Ocean for hundreds of miles. If you're in a town like Juneau, you can't even drive out. There are no roads connecting Juneau to the rest of the world. You have to take a ferry or a plane. Looking at the map, you’d assume you could just hop over the mountains into Canada, but the terrain is so vertical and glaciated that it’s nearly impossible.

Time Zones Are a Hot Mess

If you look at a time zone map overlaying the map of United States Canada and Alaska, your brain might start to hurt.

👉 See also: Is Barceló Whale Lagoon Maldives Actually Worth the Trip to Ari Atoll?

Newfoundland, way out on the eastern edge of Canada, has its own time zone that is 30 minutes off from everyone else. Then you have Alaska, which covers a span of longitude that should naturally encompass four different time zones. To make life easier, the state government jammed almost the entire state into a single "Alaska Time Zone."

This means in parts of western Alaska, the sun might not set until nearly midnight in the summer, and it doesn't rise until lunchtime in the winter. The map tries to organize this with neat vertical lines, but the reality is a chaotic dance of sunlight and shadows that dictates how people actually live in these northern latitudes.

How to Actually Use This Information

If you're studying a map of United States Canada and Alaska for travel or education, stop looking at the 2D versions.

Go to Google Earth. Rotate the globe. Look at the "Great Circle" routes.

You’ll see that if you fly from New York to Tokyo, you don't fly across the Pacific. You fly right over the top of Canada and Alaska. The map makes it look like a detour, but the curvature of the Earth makes it a shortcut. This is why Anchorage is one of the busiest cargo hubs in the entire world. It sits at the "crossroads" of the modern map, even though it looks like it's at the end of the world.

Essential Realities for Your Next Trip

- The Border is Real: Don't let the vast wilderness fool you. Crossing between the US, Canada, and back into Alaska requires a passport and patience.

- Scale Matters: You cannot drive from Vancouver to Anchorage in a day. It’s a 40-hour haul through some of the most unforgiving terrain on the continent.

- Wildlife Overlap: The map shows borders, but the animals don't care. The Porcupine Caribou herd migrates across the Alaska-Yukon border every year. Their survival depends on both countries managing the land as one ecosystem.

- Check the Projections: If you’re buying a map for your wall, look for a "Lambert Conformal Conic" projection. It’s much more accurate for showing the mid-to-high latitudes of North America without making Alaska look like a continent of its own.

Geography isn't just about where things are. It’s about how we see them. The way we draw the map of United States Canada and Alaska shapes how we think about resources, travel, and even politics. When you look past the colored lines and the distorted sizes, you see a massive, interconnected wilderness that defines the spirit of the entire northern hemisphere.

Grab a physical globe sometime. Run your finger from the Florida Keys up through the Canadian Rockies and over to the Aleutian Islands. That’s the only way to truly feel the scale of what you're looking at.

Next Steps for Mapping Enthusiasts

If you want to dive deeper into the reality of North American geography, your next move should be exploring the National Land Cover Database (NLCD) or the Natural Resources Canada maps. These don't just show borders; they show the actual terrain—from the muskeg of the Northwest Territories to the temperate rainforests of the Alaskan Panhandle.

For those planning a journey through these regions, download offline maps via Gaia GPS or onX. The "Alaska Gap" is famous for eating cell signals, and a digital map won't help you if it can't ping a tower. Understanding the topographic reality behind the flat map is the difference between a successful expedition and getting stuck in the middle of the Yukon with no bars and a very confused GPS.