Maps are weird. We look at a map of the world with countries and continents and think we’re seeing reality, but honestly, we’re just looking at a very clever mathematical compromise. It’s impossible to flatten a sphere onto a piece of paper without stretching something. Think about an orange peel. If you try to press it flat, it rips. To avoid the "rip," mapmakers stretch the land.

You’ve probably seen the Mercator projection your whole life in classrooms. It makes Greenland look like it’s the size of Africa. In reality? Africa is fourteen times larger. That’s a massive gap. This isn't just a design choice; it’s a quirk of 16th-century navigation needs that stuck around way longer than it should have.

The Seven (or Eight) Continents Dilemma

We’re taught there are seven continents. North America, South America, Europe, Asia, Africa, Australia, and Antarctica. Simple, right? Not really.

Geology doesn't care about our borders. If you look at a tectonic map, Europe and Asia are one giant slab of rock called Eurasia. The division is purely cultural and historical. Russia sits on both. Istanbul literally straddles the line. Then you have Zealandia. Most of it is underwater, but geologists now argue it's a legitimate eighth continent. It’s a massive landmass that broke off from Gondwana about 80 million years ago.

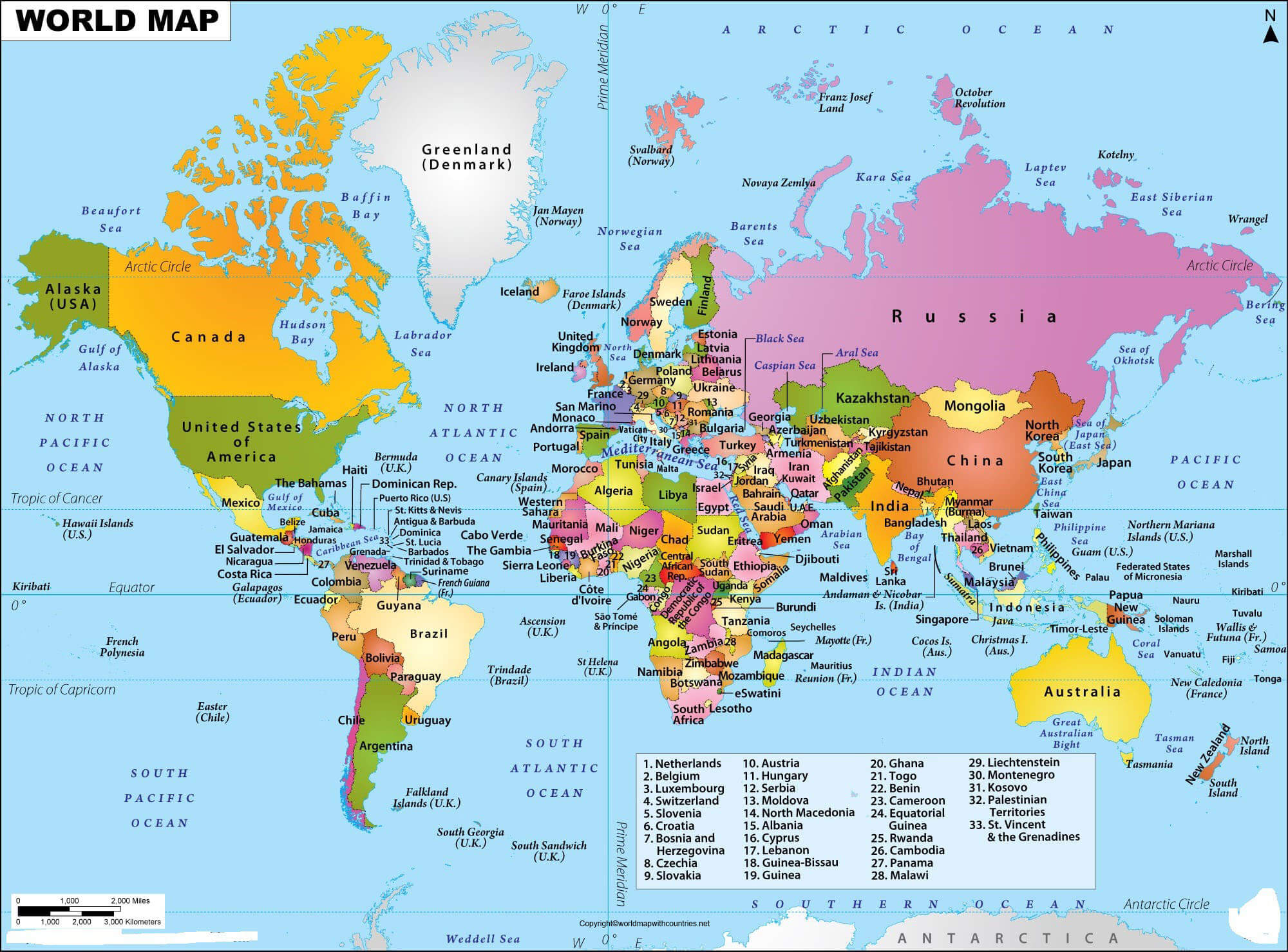

And what about the borders on a map of the world with countries and continents? They change more often than you'd think. Since 1990, over 30 new countries have appeared. South Sudan is the youngest, born in 2011 after decades of civil war. When you look at a map, you're looking at a snapshot of a political moment, not a permanent truth.

Why Africa is Always Smarter Than the Map Suggests

Let’s talk about the "True Size" problem. Because of the way we project maps, the Global North looks huge. Canada and Russia look like they swallow the planet.

💡 You might also like: Converting 50 Degrees Fahrenheit to Celsius: Why This Number Matters More Than You Think

But Africa is gargantuan. You can fit the United States, China, India, Japan, and most of Europe inside the borders of Africa, and you’d still have room left over. This matters. When we visualize the world incorrectly, we subconsciously assign "importance" based on size. The Gall-Peters projection tries to fix this by showing the actual relative sizes of landmasses, but it makes the continents look "stretched" and long. It’s a trade-off. You can have the right shape, or the right size, but you rarely get both.

The Messy Reality of Country Borders

Borders aren't just lines. They are often the result of messy history, colonial pencils, and active disputes. Take the Diomede Islands. One is Russian, one is American. They are only about 2.4 miles apart. You can literally see "tomorrow" from the American side because the International Date Line runs right between them.

Then you have the "Enclave" madness. Look at the border between India and Bangladesh before the 2015 land swap. There were pieces of India inside Bangladesh, which contained pieces of Bangladesh, which contained a tiny piece of India. It was a cartographic Russian nesting doll. Most maps of the world with countries and continents just ignore these details because they are too small to draw, but for the people living there, the map is a daily logistical nightmare.

The Problem with "Oceania"

Is Australia a country or a continent? Both. But in many parts of the world, students aren't taught "Australia" as the continent name. They learn "Oceania." This region includes thousands of islands across the Central and South Pacific.

Mapping this area is a nightmare. Do you focus on the vast blue space, or do you zoom in so much that the continents disappear? Most maps choose the latter. This erases the scale of the Pacific Ocean, which is actually larger than all the Earth's land area combined. You could fit every single continent into the Pacific and still have room for another Africa. That is a staggering amount of water that your standard wall map usually shrinks to make the countries look better.

📖 Related: Clothes hampers with lids: Why your laundry room setup is probably failing you

Understanding Projections: Choose Your Fighter

If you're looking for a map of the world with countries and continents that actually feels "right," you have to pick your projection based on what you need.

- Mercator: Great for sailing a ship in 1569. Terrible for understanding how big Africa is.

- Winkel Tripel: This is what National Geographic uses. It’s a "compromise" projection. It distorts everything a little bit so that nothing is distorted a lot. It’s probably the most "honest" look we have.

- Dymaxion: Created by Buckminster Fuller. It unfolds the earth into a 20-sided shape. It has no "up" or "down" and shows the continents as one nearly continuous island. It’s brilliant, but it’s a headache to read if you’re looking for a specific city.

- AuthaGraph: This Japanese projection is arguably the most accurate map in existence. It maintains the proportions of land and water incredibly well, but it looks "tilted" to our untrained eyes.

Geopolitics and the "Unrecognized" States

A standard map shows about 193 to 195 countries. But if you ask the people in Taiwan, Kosovo, or Somaliland, that number changes. Maps are political statements.

Google Maps actually changes its borders depending on which country you are viewing them from. If you look at the border between India and Pakistan while in New Delhi, you see one thing. If you look while in Islamabad, you see another. The "map of the world" is not a settled document. It's a living, breathing argument between nations.

The Role of Antarctica

Most people think of Antarctica as a big white strip at the bottom of the map. In reality, it’s a circular continent covered in ice miles thick. It’s not "owned" by anyone, thanks to the 1959 Antarctic Treaty, but various countries have "claims" that look like slices of a pie. On many maps, these claims aren't even shown because they aren't technically sovereign borders. It’s a weird legal gray zone that covers 5.5 million square miles.

Actionable Steps for Using a World Map Effectively

If you’re using a map of the world with countries and continents for education, decor, or travel planning, stop treating it as a literal photograph of Earth. It’s an interpretation.

👉 See also: Christmas Treat Bag Ideas That Actually Look Good (And Won't Break Your Budget)

Compare Projections Digitally Go to a site like "The True Size Of." You can drag countries like the UK or the USA over the equator and watch them shrink. It’s the fastest way to unlearn the Mercator bias we all grew up with. It’ll change how you see the world's power balance instantly.

Check the "Date of Publication" If your map still shows "Swaziland" (now Eswatini) or "Macedonia" (now North Macedonia), it’s outdated. Even "Turkey" officially changed its international name to "Türkiye" recently. A map older than five years is likely missing a name change or a border shift.

Look Beyond the Seven Continents Start thinking in terms of "biomes" or "tectonic plates" if you want to understand the physical world. The "continent" model is a human invention designed to categorize people and cultures, but it often fails to explain how the planet actually works.

Understand the Center Point Most maps sold in the US are Americas-centered. Maps sold in China often center the Pacific. European maps center the Prime Meridian. There is no "top" or "center" of the world. Rotating your map or looking at a South-up map (where Antarctica is at the top) is a great exercise in breaking your brain's geological prejudices.

Maps are tools, not just pictures. Every time you look at one, you're seeing a choice made by a cartographer about what matters and what doesn't. Size, shape, or direction—you usually have to sacrifice one to get the others.

Next Steps for Exploration

- Use the Winkel Tripel projection for the most balanced visual representation of landmasses.

- Reference the UN List of Member States if you need a definitive "official" count of countries for legal or academic work.

- Explore Topographic maps rather than political ones if you want to understand why certain borders exist where they do (hint: it’s usually because of a mountain range or a river).