Texas is huge. You know that. But if you look at a vintage map of texas indian tribes, you’re usually looking at a frozen moment in time that doesn't actually exist. History isn't a polaroid; it's a movie. People moved. They fought. They traded. They disappeared into other cultures. Most of those static maps we saw in fourth-grade social studies make it look like every tribe had a neat little fence around their backyard.

They didn't.

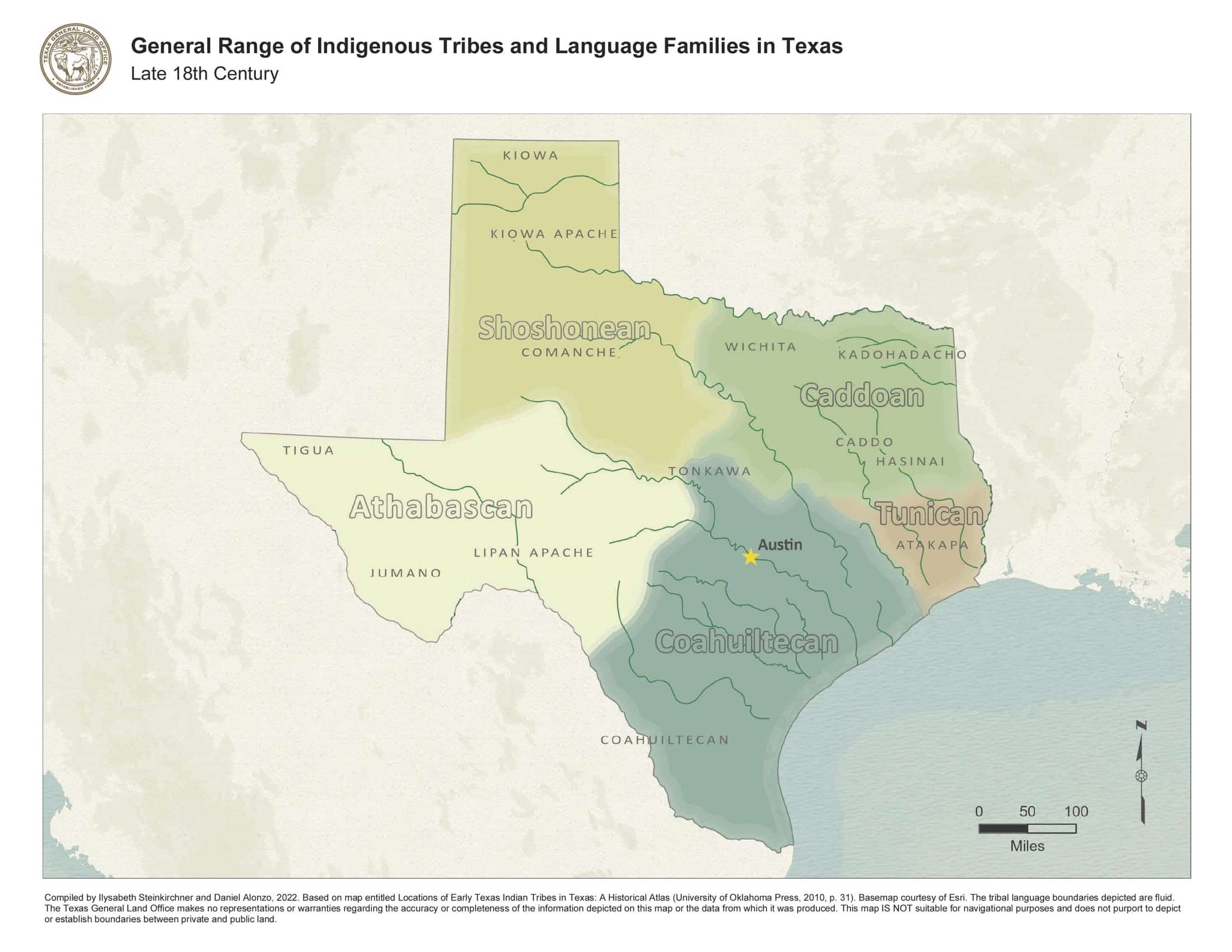

Texas was a chaotic, shifting landscape of migration and power struggles long before a single European boot hit the mud at Galveston. If you want to understand the real layout of Indigenous Texas, you have to stop thinking about borders and start thinking about ranges. The Caddo weren't just "in the east"; they were an empire of mounds and trade. The Comanche weren't just "in the west"; they were a mobile superpower that dictated the terms of survival for everyone else for over a century.

The Great Misconception of the "Static" Map

Most people pull up a map of texas indian tribes and expect to see clear lines. Red for Apache, blue for Karankawa, green for Caddo. That's a fantasy. Honestly, a map from 1500 looks nothing like a map from 1700, and by 1850, the whole thing had been turned upside down.

Take the Jumano. They are one of the most mysterious groups in Texas history. In the 1500s and 1600s, they were everywhere—acting as middlemen between the farming tribes of the East and the Pueblo peoples of New Mexico. They had these distinct horizontal tattoos on their faces. But by the 1700s? They basically vanish from the maps. Why? Because the Lipan Apache moved south and hammered them, and the remaining Jumano either joined the Apache for survival or merged into Spanish missions.

If your map doesn't show that movement, it's lying to you.

Then there’s the issue of names. A lot of the names we use today were actually insults given by their enemies or confused labels from Spanish explorers. "Karankawa" might actually be a broad term for several distinct groups like the Cocos and the Copanes who shared a similar culture along the Gulf Coast. We’ve spent centuries trying to fit these fluid, complex societies into little boxes on a piece of paper. It just doesn't work that way.

The Caddo: The Sophisticated East

In the Piney Woods, things were different. While people often associate Texas Indians with nomadic buffalo hunters, the Caddo were the heavyweights of the East. They built massive earthwork mounds that still stand today at the Caddo Mounds State Historic Site. These weren't just dirt piles. They were the centers of a highly stratified society with a clear religious and political hierarchy.

They lived in large, grass-thatched houses that looked like giant beehives. They were farmers. They grew corn, beans, and squash. They made pottery that was so good it was traded as far away as the Great Lakes. When you look at a map of texas indian tribes, the Caddo occupy the northeast corner, but their influence stretched way beyond that. They were the reason the Spanish called the area "Tejas"—from the Caddo word taysha, meaning friends.

The Caddo didn't just wander around. They stayed put until they were forced out. By the time the Republic of Texas was formed, these settled farmers were seen as a "problem" because they sat on prime agricultural land. It’s a dark chapter. They were eventually pushed into Oklahoma, but their DNA is literally written into the soil of East Texas.

The Comancheria: A Map Within a Map

You can't talk about Texas without the Comanche. But here’s the thing: they weren't originally from Texas.

The Comanche split from the Shoshone in Wyoming and moved south in the early 1700s. They were the first group to fully master the horse, and it turned them into the most formidable light cavalry in the world. They didn't just live in the Texas Panhandle; they owned it. Historian Pekka Hämäläinen calls it the "Comanche Empire," and he’s right.

Power Dynamics on the Plains

They pushed the Apache out of the Southern Plains. They raided deep into Mexico. They halted Spanish expansion for decades. If you look at a map of texas indian tribes from 1800, you’ll see a massive area labeled "Comancheria." This wasn't a country with a capital building, but it had clear rules. If you wanted to cross it, you paid a toll in trade goods or you took your life in your hands.

- The Horse: It changed everything. It allowed them to hunt buffalo with terrifying efficiency.

- The Trade: They weren't just raiders; they were savvy businessmen who traded horses and captives for guns and metal goods.

- The Lords of the South: By the time the Texas Rangers became a thing, they were playing catch-up to a military force that had been dominant for a century.

The Coastal People and the Cannibalism Myth

Down on the coast, you had the Karankawa and the Coahuiltecan. These groups lived a tough life. The Karankawa were famously tall—many over six feet, which was huge for that era—and they covered themselves in shark liver oil to keep the mosquitoes away.

History has been mean to the Karankawa. Early explorers like Cabeza de Vaca and later Stephen F. Austin labeled them as "cannibals." Modern scholars like Dr. Todd Smith have pointed out that while there might have been ritualistic practices, the "bloodthirsty cannibal" trope was mostly used as an excuse to justify their extermination. They were a maritime people, experts with dugout canoes and longbows made of cedar.

The Coahuiltecans were further south, in the brush country. They were foragers. They ate everything the land gave them—prickly pear, mesquite beans, even insects. They were the primary residents of the San Antonio missions. When you visit the Alamo or Mission San Jose, you aren't just looking at Spanish history; you’re looking at the place where Coahuiltecan culture was forcibly blended into what we now call Tejano culture.

How to Read a Modern Map of Texas Indian Tribes

If you're looking for a map today, you need to look for two things: Ancestral Lands and Current Reservations. Most of the original tribes are gone from the state, but three are officially recognized and have land in Texas:

✨ Don't miss: Why the Search for the Most Disgusting Pimple Pop Ever 2023 Still Obsesses the Internet

- The Alabama-Coushatta: Located in the Big Thicket of East Texas. They actually helped the Texas army during the Revolution, which is why they were allowed to stay.

- The Ysleta Del Sur Pueblo (Tigua): Located near El Paso. They came south with the Spanish during the Pueblo Revolt in 1680.

- The Kickapoo Traditional Tribe of Texas: Based near Eagle Pass. They are incredible because they’ve maintained their traditional ways of life despite moving between Mexico and the U.S. for generations.

The Lingering Ghost of the Lipan Apache

The Apache are a tricky group for map-makers. They were nomadic and incredibly resilient. They were the primary rivals of the Comanche. While the Comanche took the High Plains, the Lipan Apache were pushed into the Hill Country and further south.

They weren't just "warriors." They were families trying to survive a pincer movement between the Comanche to the north and the Spanish/Mexicans to the south. Today, the Lipan Apache Tribe of Texas is very active, though they don't have a federal reservation in the state. They are a "state-recognized" tribe, and their presence is a reminder that being removed from a map doesn't mean you've stopped existing.

The Reality of Displacement

By the mid-1800s, the map of texas indian tribes was basically a map of ethnic cleansing. Mirabeau B. Lamar, the second president of the Republic of Texas, had a policy of total "extinction" or removal. He didn't want a "middle ground." He wanted them out.

The Cherokee, led by Chief Bowles (a friend of Sam Houston), were driven out in 1839. They had lived in East Texas for decades after fleeing pressure in the Southeast. They had farms. They had a written language. It didn't matter. They were forced north into Oklahoma in a bloody conflict.

This is why most "Indian" history in Texas feels like it ends in 1874 at the Battle of Palo Duro Canyon. That’s when the last of the free-roaming Comanche and Kiowa were forced onto reservations in Oklahoma. But the people didn't vanish. Their descendants are still here. They’re lawyers, teachers, and artists. They’re part of the fabric of the state.

Actionable Steps for Exploring This History

If you really want to move beyond a static piece of paper and understand the Indigenous history of Texas, don't just stare at a screen. Do this instead:

- Visit the Caddo Mounds: Go to Alto, Texas. Stand on the mounds. Look at the landscape. It’s the only way to feel the scale of the civilization that lived there for over 1,000 years.

- Use Native-Land.ca: This is a great digital resource. It’s an interactive map that shows indigenous territories, but it uses overlapping colors to show how these lands were shared or contested. It's way more accurate than a standard textbook map.

- Support the Living: Check out the Bullock Texas State History Museum in Austin. They have excellent exhibits that were actually vetted by tribal members.

- Read "The Comanches" by T.R. Fehrenbach: It’s an older book and has some of the biases of its time, but it captures the sheer power of the Comancheria better than almost anything else. For a more modern perspective, read S.C. Gwynne’s Empire of the Summer Moon.

- Look at the Place Names: Next time you’re driving, look at the signs. Waxahachie, Nacogdoches, Anahuac. These aren't just random words; they are the linguistic fingerprints of the people who owned this land long before it was called Texas.

The map is just the beginning. The real story is in the movement, the survival, and the people who are still telling these stories today. Native history in Texas isn't a "chapter"—it's the foundation of the whole book.