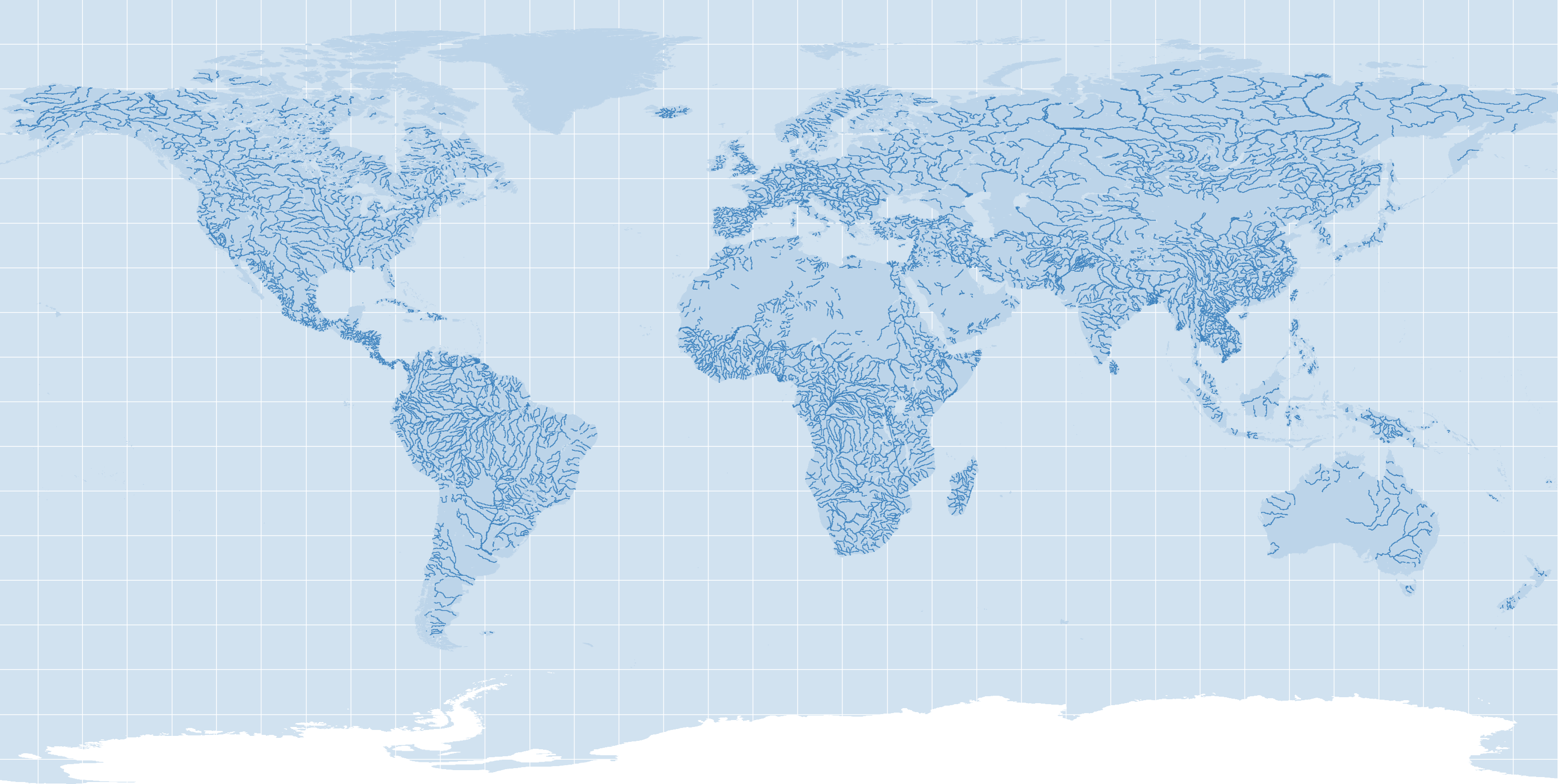

Water is weird. Honestly, we look at a map of major rivers in the world and think we see static blue lines, like veins on a stagnant hand. But rivers aren't lines. They’re pulses. If you’ve ever stood on the banks of the Amazon during the "wet" season, you know that the line on your map is basically a suggestion. The river doesn't just flow; it breathes, expanding by miles into the surrounding jungle until the "riverbank" is just a memory under fifteen feet of coffee-colored water.

Most people pull up a global river map because they want to know which one is the longest. Is it the Nile? Is it the Amazon? It depends on who you ask and how much they like arguing about "true sources." Scientists have been bickering over this for decades. Mapping these giants isn't just about drawing lines; it's about understanding how the planet moves its most precious resource from the mountains to the sea.

The Great Length Debate: Nile vs. Amazon

You’ve probably heard the Nile is the longest. That’s what the old textbooks said. It stretches roughly 6,650 kilometers (4,130 miles) through eleven countries. It’s the lifeline of Egypt. Without it, that entire civilization simply wouldn't exist. But here’s the thing—Brazilian researchers have been claiming for years that the Amazon is actually longer if you trace it from a different starting point in the Peruvian Andes.

They suggest the Amazon is about 6,992 kilometers.

If they're right, the map of major rivers in the world needs a massive rewrite. But length is a vanity metric anyway. If we talk about volume, the Amazon wins by a landslide. It carries more water than the next seven largest rivers combined. It’s so massive that it pushes a plume of freshwater 100 miles out into the Atlantic Ocean, actually diluting the saltiness of the sea far from the coast.

💡 You might also like: Leonardo da Vinci Grave: The Messy Truth About Where the Genius Really Lies

Why the Congo River is Scarier Than You Think

When you look at Africa on a river map, your eyes go to the Nile. That's a mistake. You should be looking at the Congo. It’s the deepest river in the world. Parts of it are over 700 feet deep. To put that in perspective, you could submerge the Space Needle and still have room to spare.

Because it’s so deep, it creates these weird "evolutionary pockets." The current is so strong in certain canyons that fish populations on one side of the river have evolved differently than the fish on the other side. They literally cannot cross the street. It’s a biological barrier that behaves like a mountain range. It’s also the only major river to cross the equator twice. Think about that for a second. It lives in both hemispheres simultaneously.

The Asian Giants and the "Third Pole"

If you zoom into a map of Asia, everything starts in the Himalayas. This region is often called the "Third Pole" because it holds so much glacial ice. From this one high-altitude freezer, we get the Indus, the Ganges, the Mekong, the Yangtze, and the Yellow River.

The Yangtze is the heavy hitter here. It’s the longest in Asia and basically powers the Chinese economy. But it’s also a cautionary tale. The Three Gorges Dam is so massive that when it filled up, it actually slowed the Earth’s rotation by a fraction of a microsecond due to the shift in mass. That is terrifying power.

📖 Related: Johnny's Reef on City Island: What People Get Wrong About the Bronx’s Iconic Seafood Spot

Then you have the Ganges. To millions, it’s not just a river; it’s a goddess, Ganga Ma. It’s one of the most spiritually significant spots on Earth, but it’s also facing an existential crisis from pollution and melting glaciers. Mapping these rivers isn't just about geography anymore; it's about tracking a disappearing water supply for billions of people.

North America’s "Old Man River" and the Great Catch

The Mississippi-Missouri system is the king of North American maps. It’s a giant plumbing system for the United States. But what most people don't realize is that the Mississippi wants to move. It’s been trying to jump its banks and flow down the Atchafalaya River for years because it’s a shorter, steeper path to the Gulf of Mexico.

The only reason New Orleans and Baton Rouge still have a river is because of the Old River Control Structure, a massive engineering project by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers that forces the water to stay in its current channel. We are basically holding a giant in a cage. If that structure ever fails, the map of major rivers in the world for North America changes overnight. Shipping stops. Cities lose their water. The river wins.

The Disappearing Rivers: A Modern Crisis

We need to talk about the rivers that don't make it to the ocean anymore. It’s a bit depressing, but it’s the reality of 2026. Look at the Colorado River in the Southwest US. On a traditional map, it ends in the Gulf of California. In reality? It usually dies in the sand miles before it hits the sea. We’ve diverted so much of it for almonds, alfalfa, and Las Vegas fountains that the delta is a ghost town.

👉 See also: Is Barceló Whale Lagoon Maldives Actually Worth the Trip to Ari Atoll?

The Amu Darya and Syr Darya in Central Asia are even worse. They used to feed the Aral Sea, which was once the fourth-largest lake in the world. Now, those rivers are sucked dry for cotton farming, and the Aral Sea is a desert filled with rusting shipwrecks. When you look at a map, ask yourself: is this where the water is, or where the water used to be?

Major Rivers by the Numbers (Sort of)

- Amazon: 20% of all global river discharge. Basically a freshwater ocean.

- Yenisei: The big one in Siberia. It flows north into the Arctic, which sounds backwards but isn't.

- Mekong: The "Danube of the East." Six countries rely on it for protein via its massive inland fisheries.

- Danube: The most international river. It touches ten countries and four capital cities. It’s the ultimate European commuter.

How to Read a River Map Like a Pro

Stop looking at just the lines. Look at the basins. A river basin (or watershed) is the total area of land where all the water drains into that river. The Amazon basin is almost the size of the contiguous United States. That’s the real footprint.

Also, pay attention to the deltas. Those triangular fans at the end of rivers are some of the most fertile—and endangered—places on Earth. The Mekong Delta and the Ganges-Brahmaputra Delta are literally sinking because we’ve dammed up the sediment that used to replenish them. A map is a snapshot of a struggle between gravity, geology, and human engineering.

Actionable Insights for the Curious Explorer

If you're using a map of major rivers in the world to plan a trip or just to understand the planet better, stop using static images. The world has moved past paper.

- Use Satellite Layers: Tools like Google Earth or Sentinel Hub let you see the actual color of the water. The Yellow River is actually yellow (silt). The Rio Negro is black (tannins). This tells you more about the chemistry of the land than any blue line ever could.

- Check Flow Data: Websites like the Global Runoff Data Centre (GRDC) provide real-time or historical flow rates. Rivers aren't the same size all year. If you visit the Zambezi in October, Victoria Falls is a trickle. In April, it’s a thunderous wall of mist.

- Follow the Dams: If you want to see how humans have "broken" the map, look for the reservoirs. Every major river, except perhaps the Amazon and a few in the Arctic, is now a series of lakes connected by concrete.

- Acknowledge the Source: Don't just look at the mouth. Trace the river back to its headwaters. Usually, it starts as a tiny, nameless spring in a place nobody visits. There’s something humbling about seeing the mighty Mississippi start as a creek you can literally hop across in Lake Itasca, Minnesota.

Rivers are the world’s circulatory system. They move nutrients, they move waste, and they move us. Mapping them is a work in progress because the rivers themselves refuse to sit still. They meander, they flood, and occasionally, they vanish. The map is just our best guess at where the water is today.