Ever stared at a map of earth with lines of latitude and longitude and wondered why we still use a system from the third century BC to find a Starbucks? It’s kinda wild. We have satellites that can read a license plate from orbit, yet our entire global navigation infrastructure relies on an invisible grid dreamt up by Eratosthenes and Hipparchus.

Most people see those lines as just math homework. They aren't. They’re the reason your plane doesn’t hit a mountain. They're how your Uber knows you're standing on the corner and not in the middle of a lake.

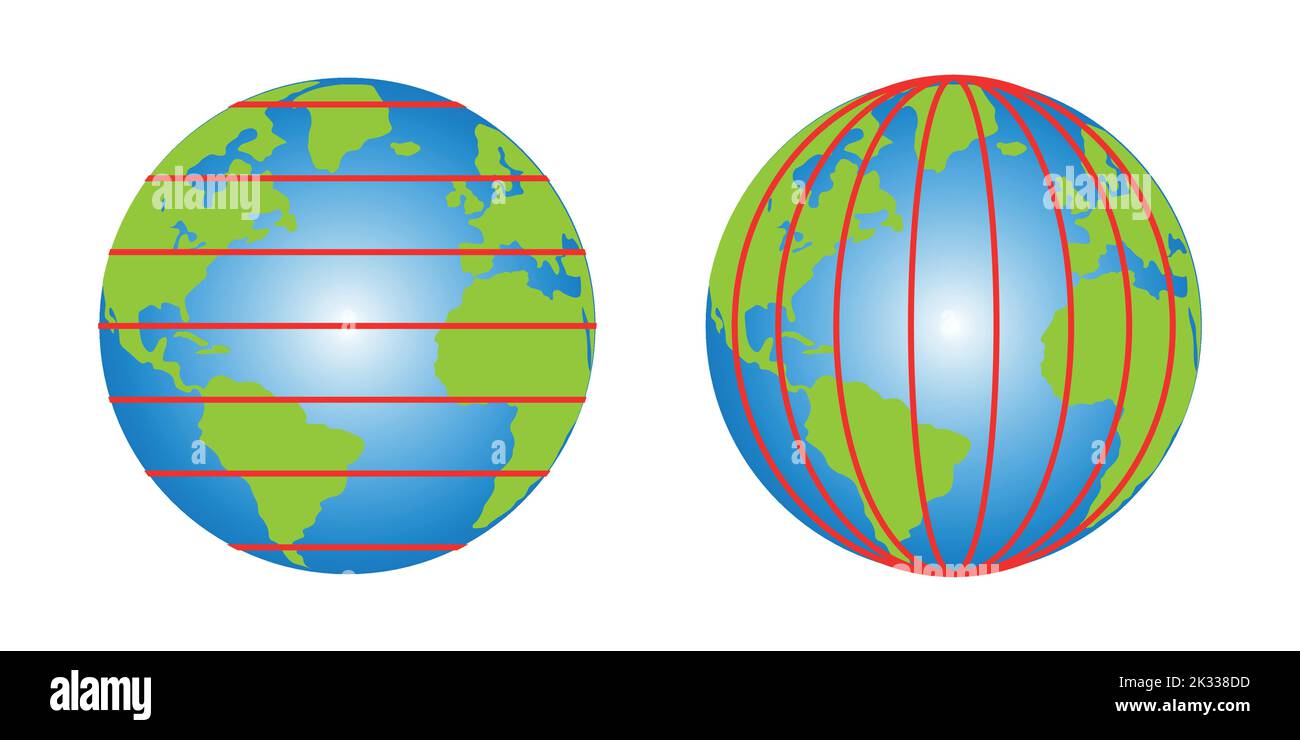

Look at a globe. Those vertical and horizontal strokes aren't just there for decoration. They are a universal language. Without them, "where are you?" becomes a philosophical crisis instead of a GPS coordinate.

The Invisible Cage: Understanding the Grid

Think of the world as an orange. If you want to tell someone exactly where a specific juice vesicle is, you need a reference point. That’s all the map of earth with lines of latitude and longitude really is.

Latitude lines, or parallels, are the easy ones. They run east-west. They’re like rungs on a ladder. The Equator is the zero-point, the big belt around the middle. As you go up toward the North Pole or down toward the South, the numbers climb until you hit 90 degrees. It’s consistent. It makes sense. If you’re at 45 degrees north, you’re exactly halfway between the Equator and the Pole. Simple.

Then there’s longitude. These are the "meridians."

They run north-south, meeting at the poles. Unlike latitude, which is based on the actual tilt and shape of the Earth relative to the sun, longitude is... well, it’s a bit of a political statement. There is no "natural" middle of the Earth vertically. We just collectively agreed in 1884 that a line running through an observatory in Greenwich, England, would be "Zero."

Why? Because at the time, the British had the best charts and most of the ships. Honestly, if the French had been more stubborn, we might all be syncing our watches to Paris Time today.

💡 You might also like: How to Convert Kilograms to Milligrams Without Making a Mess of the Math

The Problem With Flat Maps

Here is where it gets messy. Earth is a spheroid. Maps are flat.

You can't peel an orange and flatten the skin without tearing it or stretching it out of shape. This is the "Mercator Projection" problem. On many maps, Greenland looks the size of Africa. It’s not. Africa is actually fourteen times larger. When you draw a map of earth with lines of latitude and longitude on a flat piece of paper, the grid lines stay straight, but the landmasses get distorted to fill the gaps.

It’s a lie. A useful one, sure, but a lie nonetheless.

Why Latitude is About the Sun (and Your Tan)

Latitude isn't just a coordinate. It's a climate profile.

If you know your latitude, you know your life. At the Equator ($0^\circ$), the sun is almost always directly overhead. No seasons, just hot and wet. Move up to the Tropics of Cancer or Capricorn ($23.5^\circ$), and you've found the limits of where the sun can ever be directly vertical.

Beyond that? You're in the temperate zones.

Ships used to calculate latitude by looking at the North Star, Polaris. If Polaris is $40^\circ$ above the horizon, you’re at $40^\circ$ latitude. It’s elegant. It’s physics. You don't even need a clock. You just need a clear night and a protractor.

📖 Related: Amazon Fire HD 8 Kindle Features and Why Your Tablet Choice Actually Matters

But longitude? Longitude was a nightmare that killed thousands of sailors.

The Longitude Prize and the Clock that Changed Everything

For centuries, sailors could tell how far north or south they were, but they had no clue how far east or west they'd drifted. If you didn't know your longitude, you ran into reefs. You starved.

To find longitude, you need to know the exact time at two places simultaneously: where you are and a "home" port. Every four minutes of time difference equals one degree of longitude.

But old clocks used pendulums. You can't use a pendulum on a rocking ship in the Atlantic. It won't work.

The British government offered the Longitude Prize—a king's ransom—to whoever could solve it. A clockmaker named John Harrison spent his life building the "H4," a marine chronometer that didn't care about waves or temperature. He essentially digitized the map of earth with lines of latitude and longitude before computers existed.

Digital Grids: How Your Phone Uses This Today

Your phone doesn't "look" at a map. It listens to pings.

GPS (Global Positioning System) is a constellation of about 30 satellites. Each one has an atomic clock that is so precise it accounts for Einstein's theory of relativity. Because gravity is weaker up there, time actually moves faster for the satellites than it does for us on the ground.

👉 See also: How I Fooled the Internet in 7 Days: The Reality of Viral Deception

If the engineers didn't adjust the math by a few microseconds, your GPS would be off by kilometers within a single day.

When your phone calculates your position, it’s just placing you on that same old map of earth with lines of latitude and longitude. It finds the intersection of your coordinates—say, $34.0522^\circ$ N, $118.2437^\circ$ W—and overlays that onto a visual image of Los Angeles.

The Great Misconceptions About the Grid

- The lines are real. Obviously, they aren't painted on the grass. But people often forget that the "Prime Meridian" has actually moved. Thanks to better satellite tech, the "real" $0^\circ$ line is about 100 meters east of the famous brass strip at the Greenwich Observatory.

- A degree is always the same size. Nope. A degree of latitude is always about 69 miles (111 km). But because longitude lines meet at the poles, a degree of longitude shrinks as you move north or south. At the Equator, it’s 69 miles. At the North Pole? It's zero.

- The Equator is the hottest place. Not necessarily. Humidity and pressure systems (the Doldrums) matter more. But the Equator is where you weigh the least! Centrifugal force from the Earth's rotation pushes you out, making you about 0.5% lighter than you are at the poles.

How to Read a Map Like a Pro

If you want to actually use a map of earth with lines of latitude and longitude without feeling like a tourist, you have to understand Minutes and Seconds.

Each degree is broken into 60 minutes (').

Each minute is broken into 60 seconds ('').

It’s just like time. One "second" of latitude is roughly 100 feet. So, if someone gives you coordinates down to the decimal or the second, they aren't just pointing at a city. They're pointing at a specific house.

Actionable Steps for Navigating the Modern World

Stop relying solely on "blue dot" navigation. It makes your brain soft. If you want to master the grid, try these:

- Switch your GPS to Decimal Degrees: Instead of "123 Main St," look at the numbers. Learn what your "home" coordinates are. It grounds you in the physical reality of the planet.

- Check the "Great Circle" route: The next time you fly, look at the flight map. You’ll notice the plane curves toward the poles instead of flying in a straight line. That’s the latitude/longitude grid proving that the shortest distance on a sphere isn't a straight line on a flat map.

- Use Geocaching: It’s a global scavenger hunt using nothing but coordinates. It’s the best way to understand how $0.001$ of a degree feels on the ground.

- Understand your "Local Noon": When the sun is at its highest point, you are exactly on your meridian of longitude. If your watch says 12:15 but the sun is peaking, you’re slightly west of your time zone’s center.

The map of earth with lines of latitude and longitude isn't just a relic from history class. It is the operating system of the physical world. Every shipping container, every missile, every "near me" Google search, and every climate model lives inside this grid. We didn't just map the world; we caged it in numbers so we could finally find our way home.