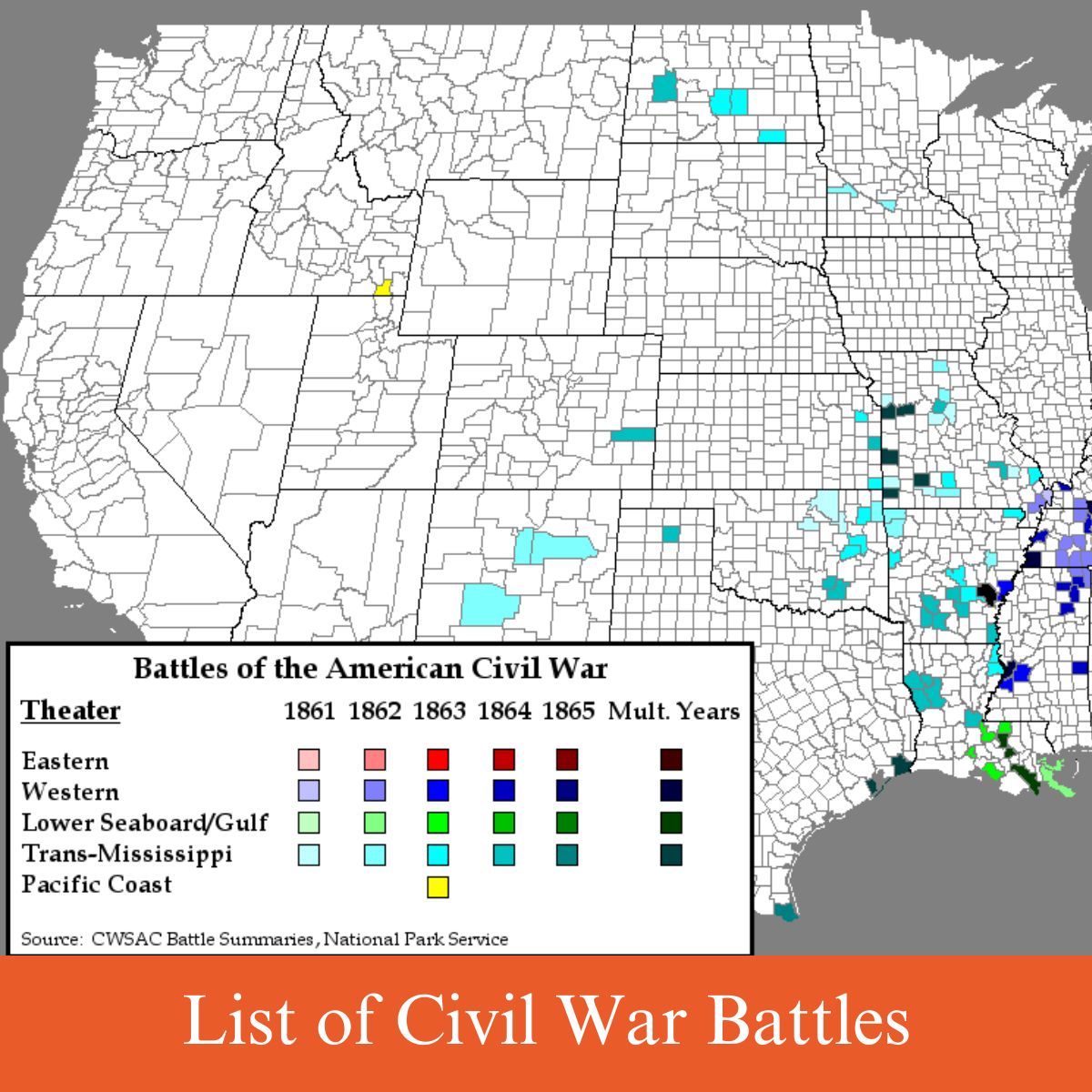

History isn't a straight line. When you look at a major battles of the civil war map, it’s easy to get lost in the sea of red and blue dots scattered across the East Coast. You see a cluster around Virginia. You see some action along the Mississippi. But maps are kind of deceptive because they staticize a war that was actually a fluid, chaotic mess of logistics and geography. Most people glance at these maps and see a series of isolated events, like "here is where Lee fought" and "here is where Grant won."

Actually, the geography of the war was the war.

If you don't understand how the Appalachian Mountains split the conflict into two distinct theaters, or why a tiny rail hub like Chattanooga was worth thousands of lives, the map is just a bunch of names you had to memorize in eighth grade. We need to look at the spatial reality of 1861 to 1865. The conflict wasn't just fought in fields; it was fought against the terrain itself.

The Eastern Theater: A Bloody Tug-of-War in a 100-Mile Box

Most of the dots on your major battles of the civil war map are crammed into a surprisingly small space between Washington D.C. and Richmond. It’s barely a two-hour drive today. Back then, it was a nightmare of rivers.

Look at the Rappahannock. Look at the Dan. Look at the James.

The North wanted Richmond because it was the political heart of the Confederacy. The South wanted to threaten D.C. to force a peace treaty. This created a literal "kill zone" in Northern Virginia. When you zoom in on a map of the Battle of Fredericksburg, you aren't just looking at troops; you’re looking at a topographical trap. Burnside’s Union forces had to cross a river and charge up Marye’s Heights. It was a vertical slaughter.

Then there’s Gettysburg. It’s often the biggest star on any map. But why there? Honestly, it was a fluke of road networks. Ten roads converged in that small Pennsylvania town. When Robert E. Lee moved North in 1863, he wasn't looking for a fight in a specific peach orchard. He was following the roads. The map tells us that the high ground—Cemetery Ridge and Little Round Top—dictated the fate of the United States. If the Union hadn't held that fishhook-shaped line, the map of the U.S. might look very different today.

📖 Related: Hairstyles for women over 50 with round faces: What your stylist isn't telling you

The Western Theater: Rivers are the Real Highways

If the East was a stalemate, the West was a bypass. While everyone was staring at Virginia, the real "game-over" moves were happening in Tennessee and Mississippi.

You’ve got to realize that the Mississippi River was the interstate highway of the 19th century. If the Union could control it, they could effectively "cork" the Confederacy. This is where a major battles of the civil war map becomes a story of water.

Vicksburg is the key.

Jefferson Davis called it the "nailhead that holds the two halves of the Confederacy together." Look at the map of Vicksburg and you’ll see a sharp U-turn in the river. The city sat on high bluffs overlooking that turn. Any Union boat trying to pass was a sitting duck. Ulysses S. Grant’s campaign to take Vicksburg wasn't just one battle; it was a months-long masterclass in amphibious warfare and swamp navigation. When Vicksburg fell on July 4, 1863—just one day after the Union victory at Gettysburg—the Confederacy was physically sliced in half. Texas, Arkansas, and Louisiana were essentially cut off.

The Importance of the Rail Hubs

Beyond rivers, look for the "X" marks on your map representing railroads.

- Corinth, Mississippi: A vital junction of the Mobile and Ohio Railroad.

- Chattanooga, Tennessee: The gateway to the Deep South.

- Atlanta, Georgia: The manufacturing hub.

The Battle of Chickamauga and the subsequent Siege of Chattanooga are perfect examples of map-based strategy. Chattanooga sits in a bowl surrounded by mountains. If you hold the heights (Lookout Mountain and Missionary Ridge), you hold the city. The Union's "Miracle at Missionary Ridge" wasn't just a brave charge; it broke the Confederate grip on the Western rail lines, clearing the path for Sherman’s March to the Sea.

👉 See also: How to Sign Someone Up for Scientology: What Actually Happens and What You Need to Know

The "Anaconda Plan" and the Coastal Map

Don't ignore the blue fringe on your major battles of the civil war map.

Winfield Scott, the aging Union General at the start of the war, proposed the Anaconda Plan. People laughed at it. They thought the war would be over in ninety days. Scott’s idea was to wrap around the South like a snake, choking it via a naval blockade.

Check out the coastal battles:

- Fort Sumter: Where it started in Charleston Harbor.

- Mobile Bay: "Damn the torpedoes!" Admiral Farragut closing the last major Gulf port.

- Fort Fisher: The "Gibraltar of the South" protecting Wilmington.

By 1864, the map shows a Confederacy that is shrinking from the outside in. The blockade wasn't 100% effective, but it turned luxury goods and basic medicines into impossible rarities. When you see the lines of Sherman’s March cutting through Georgia and the Carolinas, you’re seeing the final stage of that constriction. He wasn't just capturing territory; he was destroying the infrastructure that appeared on the map.

What Most Maps Get Wrong About the End

Common maps usually end with a big star at Appomattox Court House. While that was the end for Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia, it wasn't the end of the war.

There were still Confederate armies in the field. Joseph E. Johnston didn't surrender to Sherman until weeks later at Bennett Place in North Carolina. The final land battle actually happened at Palmito Ranch in Texas—well after Lincoln had been assassinated.

✨ Don't miss: Wire brush for cleaning: What most people get wrong about choosing the right bristles

If your map doesn't show the Trans-Mississippi Department, it's ignoring a massive part of the logistical struggle. The war was a continental event. It reached as far west as New Mexico (Battle of Glorieta Pass) and as far north as St. Albans, Vermont (a Confederate raid from Canada).

How to Actually Use a Civil War Map for Research

If you’re trying to truly grasp the scope of these conflicts, you need to layer your information. Don't just look at a flat image.

Look at the Elevation: Use topographical maps. You’ll suddenly understand why the Union struggled at places like Kenesaw Mountain. The terrain was a force multiplier for the defense.

Follow the Logistics: Trace the "Orange and Alexandria Railroad." See how many battles occurred just to keep that one line open. Armies of 100,000 men can't live off the land forever; they are tethered to the map by iron rails and river docks.

The Human Cost Per Square Inch: Some of the bloodiest spots on the map are tiny. The "Bloody Angle" at Spotsylvania or the "Sunken Road" at Antietam represent thousands of casualties in spaces no larger than a suburban cul-de-sac.

Actionable Steps for History Enthusiasts

To move beyond a basic understanding of a major battles of the civil war map, you should actively engage with the primary geography.

- Download the American Battlefield Trust app: They have GPS-enabled battle maps that show you exactly where you are standing in relation to the troop movements. It’s the best way to see the "then and now."

- Compare 1860 Census Maps with Battle Maps: If you overlay slave population density with battle sites, the political motivations for certain campaigns (like the Emancipation Proclamation's timing after Antietam) become much clearer.

- Study the "Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies": These contain the original hand-drawn maps used by generals. They are often messy, incomplete, and show exactly how much "fog of war" existed.

- Visit a "Small" Site: Everyone goes to Gettysburg. Try visiting a place like Cedar Creek or Franklin. The scale is smaller, and you can often see the entire "map" of the battle from a single ridge, which makes the tactical decisions much easier to understand.

Geography was the silent general of the Civil War. It dictated where men marched, where they starved, and where they died. By looking at a map not as a list of places, but as a series of obstacles and opportunities, you start to see the war as the leaders of the time saw it—a giant, deadly game of chess played across three million square miles of American soil.