You’ve seen the guy at the gym. He’s leaning back so far on the cable machine that he’s basically doing a horizontal row, yanking the bar toward his belly button with everything but his actual lats. It’s painful to watch. But honestly, most of us are just guessing when we clip a different attachment onto that carabiner. We swap a long bar for a V-grip because we saw a pro do it on Instagram, or maybe just because the long bar was being used by someone else. The reality is that the different types of lat pulldowns aren't just aesthetic choices; they change the internal leverage of your shoulders and determine whether you’re actually hitting your lats or just overworking your biceps and traps.

If you want a wider back, you have to understand mechanics. It isn't just "pulling weight down."

🔗 Read more: How to Do Front Squats Without Killing Your Wrists or Choking Yourself

The Standard Overhand Lat Pulldown: Is It Overrated?

Most people start here. The wide-grip, overhand lat pulldown is the poster child for back day. You grab the bar outside shoulder width, tuck your knees under the pads, and pull. But here’s the thing: going "ultra-wide" is usually a mistake. Research, including a notable study published in the Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, suggests that a grip roughly 1.5 times shoulder width is the sweet spot for activating the latissimus dorsi. When you go too wide, you actually shorten the range of motion. You’re doing less work. It feels harder because your leverage sucks, not because you're stimulating more muscle growth.

Kinda counterintuitive, right?

Focus on the "elbow lead." Think about driving your elbows into your back pockets. If you’re pulling with your hands, your forearms will give out long before your back does. You've probably felt that burn in your palms or wrists—that's a sign your grip is taking over. Use straps. Seriously. Even if you think your grip is strong, straps allow you to treat your hands like hooks, mentally disconnecting the arms so the lats can do the heavy lifting.

Close Grip and V-Bar Variations

Then we have the close-grip pulldown, usually done with that V-tapered handle. This version is a favorite for people trying to get that "thickness" in the mid-back, though "thickness" and "width" are often simplified terms for complex muscular recruitment. When you use a close, neutral grip (palms facing each other), your elbows naturally tuck closer to your sides. This puts the lats in a stronger mechanical position and allows for a massive stretch at the top.

The range of motion is huge here.

Because your hands are closer together, you can pull the handle lower, often touching your upper chest. This emphasizes the lower fibers of the lats. If you struggle to "feel" your back working during different types of lat pulldowns, the neutral grip is usually the fix. It’s harder to mess up. You aren't flaring your elbows out to the sides, which saves your rotator cuffs from a lot of unnecessary grinding.

One thing to watch out for is the "ego lean." Because you're stronger in this position, it's tempting to load the whole stack and turn it into a rhythmic rocking motion. Don't. Keep your torso relatively still, maybe a 10-degree lean back, and let the muscle stretch.

The Underhand (Reverse) Grip Pulldown

This one is basically a chin-up in machine form. By flipping your palms toward your face, you pull the biceps into a position of power. You’ll notice you can move significantly more weight this way. Is that cheating? Not necessarily. It’s just a different tool.

According to various electromyography (EMG) studies, the underhand grip produces high levels of activation in the lower lat fibers. It also recruits the biceps heavily. If you’ve already smashed your back with heavy rows and your lats are fried, switching to an underhand pulldown can help you squeeze out more volume because the biceps act as a "backup generator" to keep the set going.

- Pro Tip: Don't wrap your thumb around the bar. Use a "suicide grip" (thumb on top). It sounds sketchy, but it helps shift the focus away from your biceps and back onto the large muscles of the posterior chain.

- Keep your chest up. If you start rounding your shoulders forward as you pull, you're just begging for an impingement issue down the road.

Unilateral and Single-Arm Pulldowns

We all have a dominant side. You might not notice it with a long bar, but your right lat is probably doing 55% of the work while your left is coasting at 45%. Over years of training, that leads to a lopsided physique and potential ribcage rotation issues. This is where the single-arm lat pulldown comes in.

Use a single D-handle. Sit sideways on the bench or kneel on the floor. This variation allows for a much more natural "arc" of movement. You can actually crunch into the working side at the bottom of the rep, intensifying the contraction of the lower lat. It’s a surgical tool. You won't use much weight, but the mind-muscle connection is usually 10x better than any bilateral movement.

Behind-the-Neck: The Controversial Classic

We have to talk about it. The behind-the-neck pulldown was a staple in the Golden Era of bodybuilding. You’ll see old footage of Arnold or Franco doing these. Nowadays, most physical therapists will tell you to never touch them.

Are they actually dangerous?

For most people, yes. Unless you have incredible shoulder mobility, pulling a rigid bar behind your head forces your humerus into an extreme position of external rotation. It puts a massive amount of stress on the rotator cuff and the labrum. There is almost no evidence that it grows the back better than pulling to the front. Honestly, the risk-to-reward ratio is garbage. If you feel a "pinch" in your shoulder joints, stop doing these immediately. Stick to the front. Your 50-year-old self will thank you.

Straight-Arm Lat Pulldowns (The Finisher)

Technically a "pullover" motion, the straight-arm version is the only pulldown that almost completely isolates the lats by removing the biceps from the equation. Since your elbows stay locked (or slightly bent but fixed), your arms act as simple levers.

This is best done at the end of a workout. Use a rope attachment or a straight bar. Stand back from the machine so there’s tension even at the top. When you pull down to your thighs, focus on "crushing" your armpits. It’s a weird cue, but it works. You’re trying to use the lats to sweep the bar down in a wide arc. If you feel it in your triceps, you’re pushing down too much; try to focus on the pull from the back.

Common Mistakes Across All Variations

People love to use momentum. If the weight is moving because you're jerking your torso like a rocking chair, your lats aren't getting the stimulus. You're just practicing being a human pendulum.

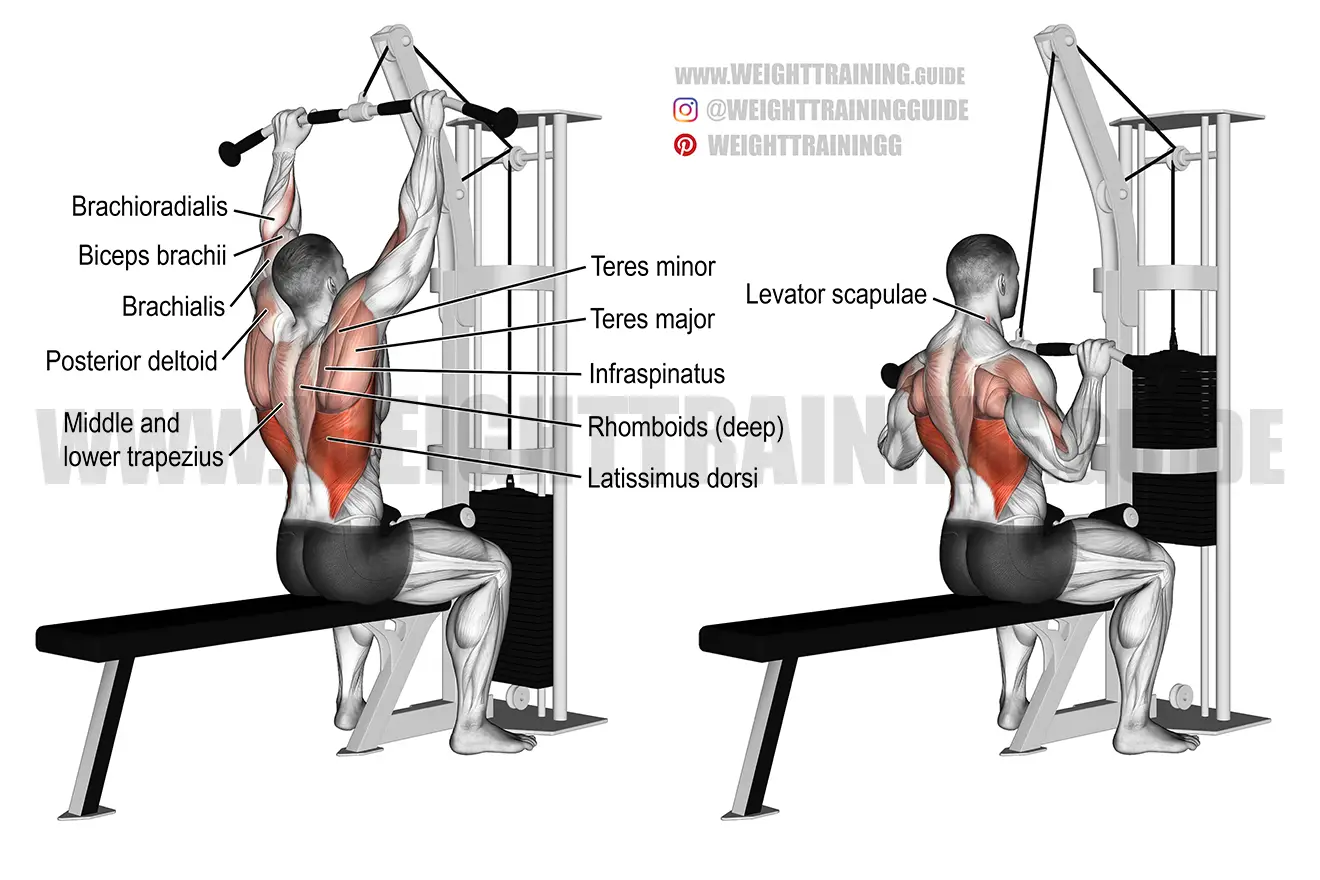

Another huge error is the "shoulder shrug." Before the bar even moves, your shoulder blades should depress. Imagine someone is trying to tickle your armpits and you're squeezing down to stop them. That "set" of the scapula is what initiates the lat recruitment. If your shoulders are up by your ears at the bottom of the movement, you’re mostly using your upper traps and levator scapulae. That leads to neck pain, not a V-taper.

💡 You might also like: Why Blood Covers the Whole Floor: The Reality of Major Trauma and Biohazard Cleanup

Optimizing Your Program

You don't need to do six different types of lat pulldowns in one session. That's overkill.

Instead, pick two that complement each other. Maybe start with a heavy, neutral-grip pulldown for strength and follow it up with a single-arm variation or a straight-arm pulldown for high-rep metabolic stress. Change your attachments every 4-6 weeks to keep the stimulus fresh. Your body adapts to the specific line of pull, so shifting from a wide bar to a multi-grip bar can jumpstart growth when you hit a plateau.

Actionable Integration Steps

- Assess Your Mobility: If you can't raise your arms straight overhead without arching your lower back, stay away from wide-grip pulldowns for a while. Stick to neutral grips until your shoulder health improves.

- The Two-Second Pause: On your next back day, hold the bottom of every rep for a full two seconds. If you can't hold it, the weight is too heavy. This forces the lats to stabilize the load.

- Vary Your Tempo: Try a 3-second eccentric (the way up). The stretch under tension is where the majority of muscle damage—and subsequent growth—happens.

- Check Your Grip: Switch to a thumbless grip for one set. Notice how much more you feel your back and how much less you feel your forearms.

- Record Your Sets: Film yourself from the side. You’ll be shocked at how much you're actually leaning back compared to how much you think you're leaning back.

Focusing on the quality of the contraction over the number on the weight stack is the fastest way to actually see progress. Stop pulling with your ego and start pulling with your back.