We all carry a map in our heads. It’s that mental image of the world we’ve been building since the third grade, usually based on a colorful poster hanging above a chalkboard or a dusty globe in the corner of a library. But here’s the problem: that map is almost certainly lying to you. Not because of some grand conspiracy, but because your brain is incredibly efficient at holding onto outdated information.

Think about it. When you picture the planet, what do you see? You likely see a world sharply divided between "developed" and "developing" nations. You probably imagine a massive gap in wealth, health, and family size that hasn’t actually existed since the 1970s. We’re walking around with a 20th-century operating system trying to navigate a 21st-century reality. It’s messy.

The Distortion of the Mercator Mindset

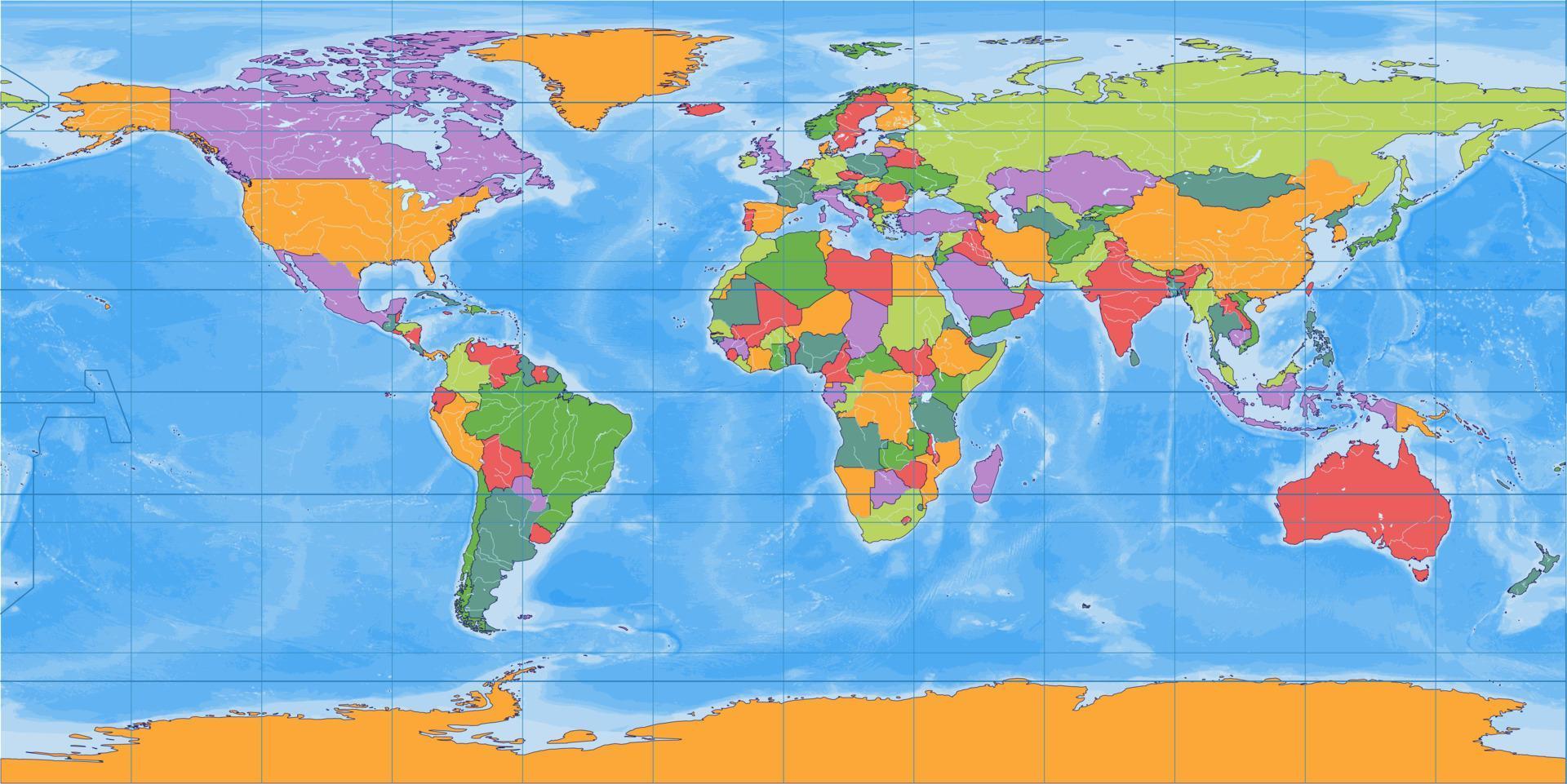

The most literal image of the world we encounter is the Mercator projection. You know the one—Greenland looks roughly the size of Africa, and Europe seems to sit right at the center of the universe. It was designed in 1569 for sailors, not for social accuracy.

Gerardus Mercator needed a map that preserved constant bearings for navigation. That’s great for a 16th-century galleon. It’s terrible for understanding the actual scale of humanity. In reality, Africa is fourteen times larger than Greenland. You could fit the United States, China, India, and most of Europe inside the African continent, and you’d still have room to spare.

🔗 Read more: Pink White Nail Studio Secrets and Why Your Manicure Isn't Lasting

When we look at these distorted maps every day, it subtly warps our sense of importance. We overestimate the size and influence of northern latitudes and shrink the Global South. It’s a visual bias that translates into economic and political bias. We start thinking that the "top" of the world is naturally bigger and more significant than the "bottom."

Why Your Mental Statistics are Stuck in 1965

The late Hans Rosling, a professor of international health and a master of data visualization, spent years proving that most people—including Nobel laureates and heads of state—have an image of the world that is worse than if they were just guessing at random. He’d ask simple questions about global poverty, vaccination rates, or girls’ education. Most people got them wrong because they assumed the world was getting worse or staying static.

Take fertility rates. Most people still think "developing" countries have six or seven children per woman. That was true in the 1960s. Today? The global average is around 2.3. Almost every country in the world, from Brazil to Bangladesh, has seen a massive shift toward smaller families.

💡 You might also like: Hairstyles for women over 50 with round faces: What your stylist isn't telling you

We tend to group the world into "us" and "them." We think there’s a billion people living in luxury and six billion living in desperate poverty. That’s just not how the data looks anymore. The vast majority of the global population lives in the middle. They aren't starving, and they aren't rich. They have bicycles or motorbikes, their kids go to school, and they have access to basic electricity.

The Digital Mirror and the Algorithm

Our modern image of the world isn’t just shaped by maps and schoolbooks anymore. It’s shaped by the glass rectangles in our pockets. Algorithms are designed to show us what we want to see, or more accurately, what will keep us scrolling. This creates a "filter bubble" that narrows our perspective until the world looks like a mirror of our own anxieties.

If you spend all day on a certain corner of the internet, your world looks like a series of impending disasters or a constant stream of political outrage. It’s an "over-dramatic" worldview. We see the outliers—the extreme tragedy or the extreme wealth—and mistake them for the average.

📖 Related: How to Sign Someone Up for Scientology: What Actually Happens and What You Need to Know

Real-World Consequences of a False Image

- Investment Blindness: Businesses miss out on the fastest-growing markets in Southeast Asia and Africa because they still view these regions through a lens of 1980s "charity" commercials.

- Policy Failures: Governments tackle problems like climate change or migration using outdated assumptions about where people are moving and why.

- Personal Anxiety: We feel more stressed because we perceive the world as more dangerous than it actually is, despite global trends showing long-term declines in extreme poverty and certain types of violence.

Correcting the Resolution

If you want a clearer image of the world, you have to actively seek out "boring" data. The sensational stuff is easy to find; the gradual, positive trends are quiet.

Look at the World Bank’s data on extreme poverty. In 1800, about 90% of the world lived in extreme poverty. Today, that number is below 10%. That is a staggering human achievement, yet most people believe the percentage has increased or stayed the same over the last twenty years.

Honestly, it’s about humility. Accepting that your childhood education gave you a snapshot of a moment that has passed. The world is more interconnected, more educated, and more "middle class" than your brain wants to admit.

Actionable Steps to Update Your Worldview

- Switch your maps. Occasionally look at a Gall-Peters projection or the AuthaGraph map. It’ll feel "wrong" at first because it’s unfamiliar, but it’ll give you a much more honest look at the actual landmass of the continents.

- Follow "Slow News." Major outlets focus on the 1% of things that went wrong today. Sources like Human Progress or Our World in Data focus on the 99% of things that are slowly improving over decades.

- Practice the "Rule of Thumb." Whenever you see a shocking headline about a whole region of the world, ask yourself: Is this an exception or the rule? Usually, it's the exception.

- Learn the "Income Levels." Stop using the words "First World" and "Third World." They are Cold War relics. Think in terms of four income levels, where most people are at Level 2 and Level 3—earning between $2 and $32 a day. It changes how you view global consumers.

- Question the "Us vs. Them" narrative. Look for similarities in daily life. Whether it's a family in Nairobi or a family in Nashville, the core desires—safety, education for kids, a better phone, a reliable roof—are remarkably consistent.

Updating your image of the world isn't just about being "correct" at a dinner party. It’s about being able to see opportunities where others see obstacles. It’s about feeling a little less hopeless about the future. The world is a much more complex, nuanced, and—surprisingly—better place than that old poster on the wall led you to believe.