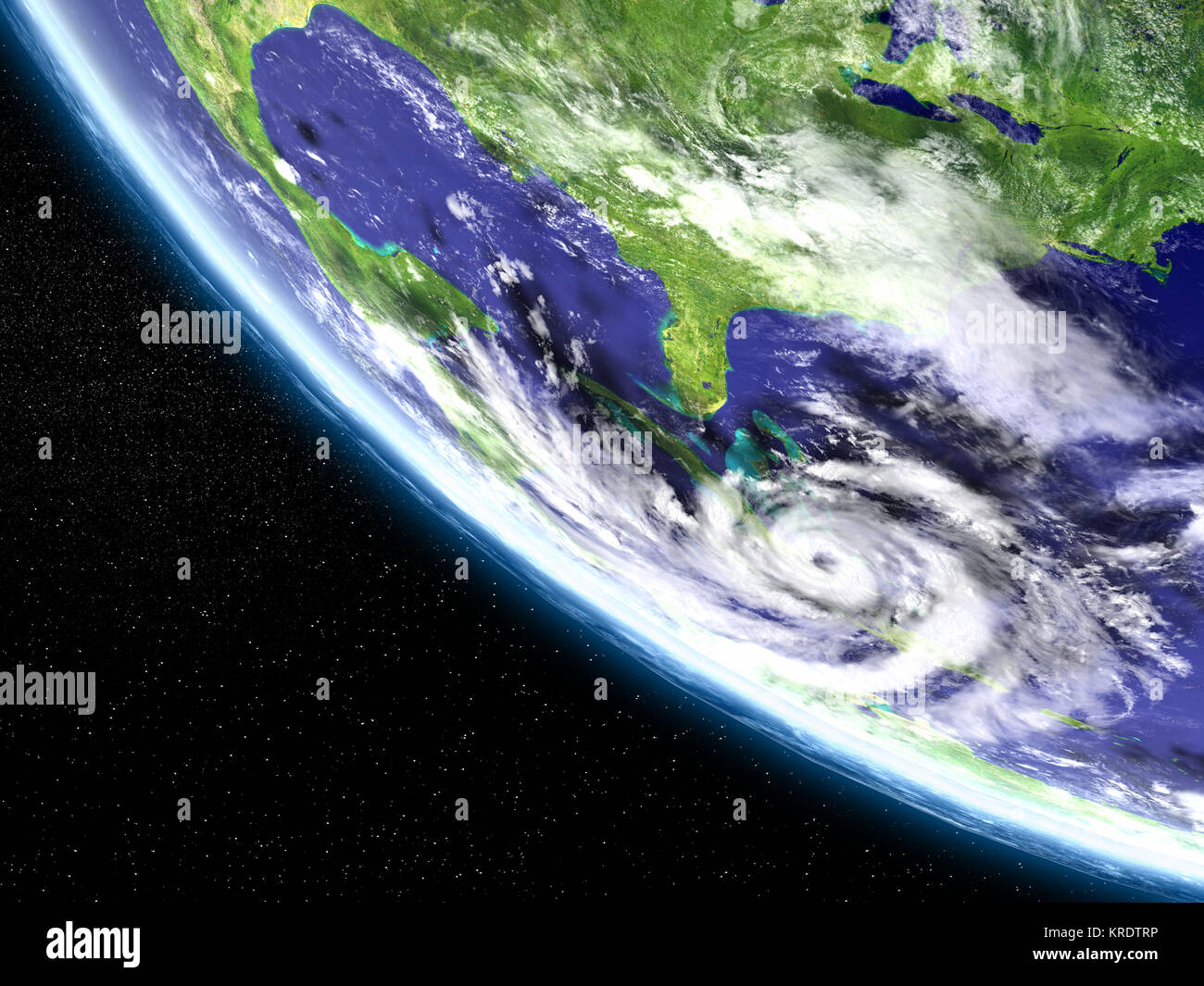

You’ve seen the images. A swirling, majestic white drain-plug in the middle of a deep blue ocean. It looks peaceful from 22,000 miles up. It looks like art. But anyone who has ever stood on a porch in coastal Louisiana or Florida as the pressure drops knows that a hurricane from satellite view is a beautiful lie. It masks the sheer, mechanical violence happening underneath those pristine clouds.

Satellites don't actually "see" a storm the way your eyes do. Not really.

👉 See also: Who Died in the New Orleans Attack: The Tragic Reality of the Mother's Day Shooting

When you look at a GOES-16 or GOES-18 image on the news, you’re often looking at a "sandwich" of different data layers. Meteorologists at NOAA (National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration) use visible light—the stuff we can see—during the day. But at night? They switch to infrared. This measures heat. Or rather, the lack of it. Those bright red and purple blobs you see on the weather channel aren't actually red clouds. They represent the freezing temperatures at the top of the storm. The colder the cloud top, the higher it is in the atmosphere, and the more likely it is that the storm is absolutely screaming with intensity.

The Eye Isn't Always the Center

It sounds counterintuitive. How can the eye not be the center?

Well, it is the geographic center of the rotation, but it isn't always where the worst of the "weather" is. From a hurricane from satellite view, the eye looks like a calm, dark hole. This is a region of sinking air. While the rest of the storm is rushing upward, air in the eye is pushing down, drying out, and clearing the clouds.

But look closer at the eyewall—that ring of clouds immediately surrounding the center.

In a powerful storm like 2005's Hurricane Wilma or 2024’s Milton, you see something called the "stadium effect." This is where the eyewall curves outward like a sports arena. From a satellite's perspective, this indicates a very mature, very dangerous system. If the eye is tiny—what they call a "pinhole eye"—it usually means the storm is spinning like a figure skater pulling their arms in. It’s accelerating.

📖 Related: St. Louis Tornado Risks: Why the Gateway City Stays on Edge

Watching the "Hot Towers"

If you're tracking a hurricane from satellite view and you see a sudden "burst" of clouds that look like they’re boiling over, pay attention. Scientists call these "hot towers." These are massive thunderstorms that punch through the top of the hurricane and reach all the way into the stratosphere.

NASA researchers have found that when these towers appear near the eyewall, the storm is likely about to undergo "rapid intensification." That’s the nightmare scenario for emergency managers. It's how a Category 1 storm becomes a Category 4 overnight while everyone is sleeping.

Why Color Schemes Matter (and Why They're Fake)

Let's be real: the ocean isn't that shade of neon blue on a weather map.

The colors are added for us. Purely for human consumption. A raw hurricane from satellite view is mostly shades of grey, white, and black. We use "enhanced" imagery to highlight temperature gradients.

- Deep Reds and Blacks: These usually indicate cloud tops colder than -70 degrees Celsius. This is where the most intense convection lives.

- Bright Greens and Yellows: These are lower, warmer clouds. They still bring rain, but they aren't the engine of the storm.

- The "Grey" Areas: Often, these are the thin cirrus clouds blowing away from the storm, known as outflow. Think of this as the hurricane's exhaust pipe. If the outflow is symmetrical and spreading out in all directions, the storm is "breathing" well and will likely stay strong.

Dr. Marshall Shepherd, a leading expert in meteorology at the University of Georgia, often points out that people get too hung up on the "skin" of the storm. The satellite shows the skin. The radar—which is often ground-based or carried on "Hurricane Hunter" aircraft—shows the bones and the blood.

The Lag Time Trap

There is a dangerous misconception that what you see on a satellite loop on your phone is happening right now.

📖 Related: Recount of Votes 2024: What Most People Get Wrong About the Numbers

It’s close, but there’s a delay. Geostationary satellites (the ones that stay over one spot on Earth) send data back every few minutes, but by the time it's processed, uploaded to a server, and pushed to your favorite app, it might be 15 to 20 minutes old. In a storm moving at 20 mph with wind gusts of 150 mph, 20 minutes is a lifetime.

Also, satellites have a hard time seeing what’s happening at the very bottom of the atmosphere. They struggle with "storm surge"—the wall of water pushed toward the shore. You can see the clouds moving, but you can't see the six feet of salt water creeping into a living room in Biloxi or Tampa.

Using Satellite Data Like a Pro

If you want to actually understand a hurricane from satellite view instead of just looking at the pretty colors, you have to look for the "scud." These are low-level clouds moving in a different direction than the high-level ones.

- Check the Water Vapor Loop: This doesn't show clouds; it shows moisture in the atmosphere. If you see a "tongue" of dry, brown air being sucked into the hurricane, the storm is in trouble. Dry air is kryptonite for a hurricane. It chokes the engine.

- Look for the Outflow: If the clouds on the edges look like they are being shredded or blown to one side, that's "wind shear." High wind shear is great for us, bad for the storm. It tilts the hurricane, making it less efficient and eventually tearing it apart.

- Nighttime Visible Imaging: The Day/Night Band on the VIIRS instrument is incredible. It can see the storm by moonlight. It can even see the city lights flickering out as the storm hits the coast. It’s a haunting way to watch a disaster unfold in real-time.

Basically, the satellite is our best early warning system, but it’s just one piece of the puzzle. It tells us where the storm is and where it’s been, but the physics of where it’s going involve complex steering currents—like the Bermuda High or mid-latitude troughs—that are invisible even to the most expensive cameras in orbit.

Actionable Insights for the Next Big One

Don't just stare at the swirling clouds. Use the data to make decisions.

- Monitor the "Mesovortices": If you see tiny little swirls inside the eye itself, the storm is extremely intense. Get out if you’re in an evacuation zone.

- Don't Trust the "Center": Satellite images of a hurricane from satellite view often show a clear eye, but the rain and wind field can extend 200 miles out from that center. Being "outside the eye" doesn't mean you're safe.

- Diversify Your Sources: Use the National Hurricane Center for official forecasts, but check tropicaltidbits.com for raw satellite loops. Look at the "Visible" loop during the day for the highest resolution of cloud structure.

- Watch the Sea Surface Temperatures: Satellites also measure how hot the water is. If a hurricane is headed for a "loop current" (a deep pool of very warm water), expect it to explode in strength, regardless of what the current wind speed is.

Understanding the view from above is about recognizing the difference between a disorganized mess of clouds and a tightly coiled heat engine. When the eye becomes a perfect, clear circle, the "lie" of the satellite's beauty is over. That’s when the real work on the ground begins.