Ever looked at a standard earth moon sun diagram in a textbook and thought, "Yeah, that looks about right"?

Honestly, it’s mostly wrong.

💡 You might also like: ISS Misses Critical Food Delivery: What Happens When Astronauts Run Out of Groceries

If you drew the solar system to scale on a regular piece of paper, the Earth would be a microscopic speck. The Moon would be an even smaller speck several inches away. And the Sun? The Sun would be a giant beach ball blocks down the street. We use diagrams because reality is too big to fit on a screen. But when we squash everything together to make it fit, we lose the "why" behind eclipses, seasons, and tides.

To really get what's happening up there, we have to look at the mechanics that most 2D drawings skip over.

The Scale Problem in Your Earth Moon Sun Diagram

Most people think the Moon is pretty close. In reality, you could fit every single planet in our solar system—Jupiter, Saturn, the whole gang—in the gap between the Earth and the Moon. That is a massive amount of empty space.

When you see an earth moon sun diagram where the Moon is hovering just a few "Earth-widths" away, it’s a lie of convenience. This matters because it explains why solar eclipses are so rare. If the Moon were as close as it looks in drawings, we’d have eclipses every single month. Instead, the Moon’s tiny size and vast distance mean its shadow usually misses us entirely.

The Sun is another story. It's about 93 million miles away. Light takes eight minutes just to get here. When we draw all three bodies in a neat little row, we’re ignoring the fact that the Sun is 400 times larger than the Moon, yet also roughly 400 times further away. This "400 rule" is a cosmic coincidence that makes the two look almost identical in size from our backyard.

The Tilt That Changes Everything

If the Earth sat perfectly upright, we’d have no seasons. Boring, right?

Our planet is tilted at about 23.5 degrees. When you're looking at an earth moon sun diagram showing the seasons, pay attention to the axis. It’s not just about being "closer" to the Sun. In fact, for those in the Northern Hemisphere, the Earth is actually closer to the Sun in January (perihelion) than it is in July (aphelion).

The heat comes from the angle.

When the North Pole tilts toward the Sun, the light hits us directly. It’s concentrated. Think of a flashlight. If you point it straight at a wall, the circle of light is bright and intense. If you tilt the flashlight, the light spreads out and gets dimmer. That’s basically winter.

Why the Moon's Orbit is "Wonky"

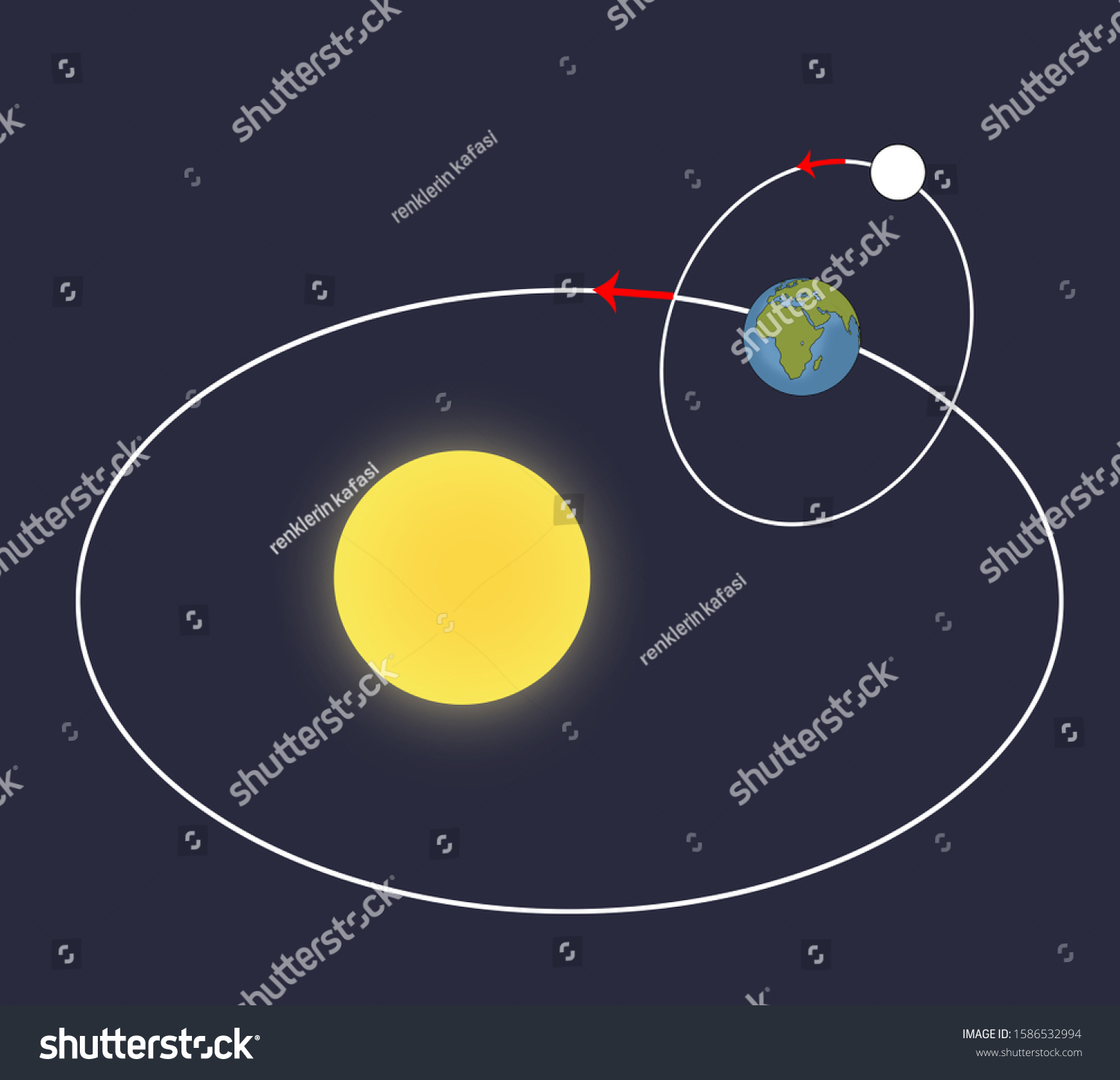

Most people assume the Moon circles our equator. Nope. The Moon’s orbit is tilted by about 5 degrees relative to the Earth's orbit around the Sun.

This is the "Ecliptic."

Because of this 5-degree tilt, the Moon usually passes "above" or "below" the Sun from our perspective. An accurate earth moon sun diagram needs to show this tilt to explain why we don't have a total solar eclipse every time there's a New Moon. The shadows just don't line up. They miss.

Eclipses: The Great Alignment

There are two main types of alignments you’ll see in these diagrams: syzygy and quadrature. Syzygy is just a fancy way of saying "three things in a straight line."

- Solar Eclipse: The Moon gets between the Earth and the Sun. It’s a New Moon phase.

- Lunar Eclipse: The Earth gets between the Sun and the Moon. This happens during a Full Moon.

Ever wonder why the Moon turns red during a lunar eclipse? It’s not because it's glowing. It's because the Earth's atmosphere acts like a lens. It bends the sunlight—specifically the red wavelengths—around the curve of the Earth and onto the Moon. Basically, you’re seeing the light of every sunrise and sunset on Earth reflected back at you at once.

Gravity and the Tug-of-War

Gravity is the invisible string in every earth moon sun diagram. While the Sun is way more massive, the Moon is way closer. This means the Moon actually has a stronger pull on our oceans.

We get "Spring Tides" (which have nothing to do with the season) when the Sun and Moon line up. Their gravity combines. The water bulges out more than usual. Then you’ve got "Neap Tides," where the Sun and Moon are at right angles to each other. They’re essentially fighting over the water, which results in much smaller tidal shifts.

The Barycenter: The Secret Center

Here is something even "expert" diagrams often miss: The Moon does not orbit the center of the Earth.

Wait, what?

The Earth and Moon actually orbit a shared center of mass called the barycenter. Because the Earth is so much heavier, the barycenter is located inside the Earth, but it’s about 3,000 miles away from the actual center. This causes the Earth to "wobble" slightly as the Moon circles it. If you were looking down from the North Star, you’d see this weird, oscillating dance.

✨ Don't miss: What Does Modal Mean? The Confusion Every Designer and Developer Hits Eventually

How to Use These Diagrams for Real-World Observation

If you're trying to teach this or just understand it for a backyard stargazing session, don't rely on one static image.

- Check the Phase: A New Moon is always between us and the Sun. That means it rises and sets with the Sun. If you see a "New Moon" in the middle of the night in a movie, the director failed science class.

- Shadow Directions: In any earth moon sun diagram, the shadows must always point directly away from the Sun. It sounds obvious, but you’d be surprised how many amateur illustrations get the shading on the Moon wrong relative to the Sun's position.

- The "L" Shape: When the Moon is at a 90-degree angle from the Sun (First or Third Quarter), it’s half-lit. This is the best time to see craters through binoculars because the long shadows on the Moon's surface make the landscape pop.

Common Misconceptions to Toss Out

People still think the "Dark Side of the Moon" is permanently dark. It isn't. It’s just the far side. Every part of the Moon gets sunlight at some point during its 27-day rotation. The only reason we don't see the back is that the Moon is "tidally locked." It rotates exactly once for every time it orbits us.

Imagine walking around a chair while always keeping your face pointed at the seat. You're rotating, but someone sitting in the chair only ever sees your nose.

Also, the "Supermoon" isn't as big as people think. The Moon’s orbit is an ellipse, not a perfect circle. When it's at "perigee" (closest point), it’s about 14% larger than at "apogee" (farthest point). You can barely tell the difference with the naked eye unless you're a seasoned pro. Most of the "huge" Moons you see in photos are just camera tricks using long zoom lenses.

Actionable Steps for Visualizing the System

To get a better handle on these mechanics without a textbook, try these steps:

Build a pocket solar system.

Take a strip of paper. Label one end Sun and the other Pluto. Fold it in half to find Uranus. Fold it again to find Saturn. You’ll quickly realize that the Earth, Moon, and Sun are all crammed into the tiny first inch of that paper. The inner solar system is incredibly crowded compared to the outer reaches.

Use a "Stellarium" style app.

Download a real-time sky map. These apps use actual data to show you the current earth moon sun diagram from your specific GPS coordinates. It’s way better than a static drawing because you can fast-forward time to see the 5-degree tilt in action.

Track the Moon's position.

Go out at the same time every night for three nights. Notice how the Moon moves further east. It’s traveling about 12 to 13 degrees across the sky every day. That’s its orbital speed visualized.

Understanding the relationship between these three celestial bodies isn't just for sailors or astronauts. It’s the clock that runs our world. Once you see past the simplified diagrams, the sky starts to make a lot more sense. You stop seeing a random white circle in the sky and start seeing a massive rock caught in a gravitational tug-of-war 238,000 miles away.

Check your local lunar calendar for the next "Node Crossing." This is the moment the Moon crosses the ecliptic plane. If that crossing happens during a Full or New Moon, you’re looking at an eclipse window. That’s the most practical way to turn a diagram into a real-world experience.