It's heavy. Honestly, there is no other way to put it. When you sit down to start a drawing of Jesus dying on the cross, you aren’t just sketching a figure; you’re wrestling with two thousand years of art history, theology, and raw human emotion. Most people struggle because they try to make it look "perfect" or "holy" right away. They forget that the Crucifixion was, fundamentally, a gritty, painful, and very physical event. If you look at the greats—guys like Caravaggio or even modern realists—they didn't shy away from the tension in the muscles or the way gravity pulls on a slumped body.

The Anatomy of Agony in Art

Getting the proportions right is a nightmare. Most beginners draw the arms straight out like a capital "T." That’s not how physics works. If a body is hanging, the weight pulls everything toward the earth. The arms should form a "V" shape, and the shoulders often look slightly dislocated because, well, in a real crucifixion, they usually were.

Look at the Isenheim Altarpiece by Matthias Grünewald. It’s terrifying. He didn't paint a porcelain-skinned Savior. He painted a man whose skin was turning blue and green, covered in sores and thorns. You don't have to go that dark, but if your drawing is too clean, it loses its soul. The ribcage usually protrudes because the lungs are gasping for air. It’s a physiological struggle. When you're sketching the torso, focus on that upward strain. It makes the piece feel alive—or, more accurately, like it's fighting to stay alive.

Why Perspective Changes Everything

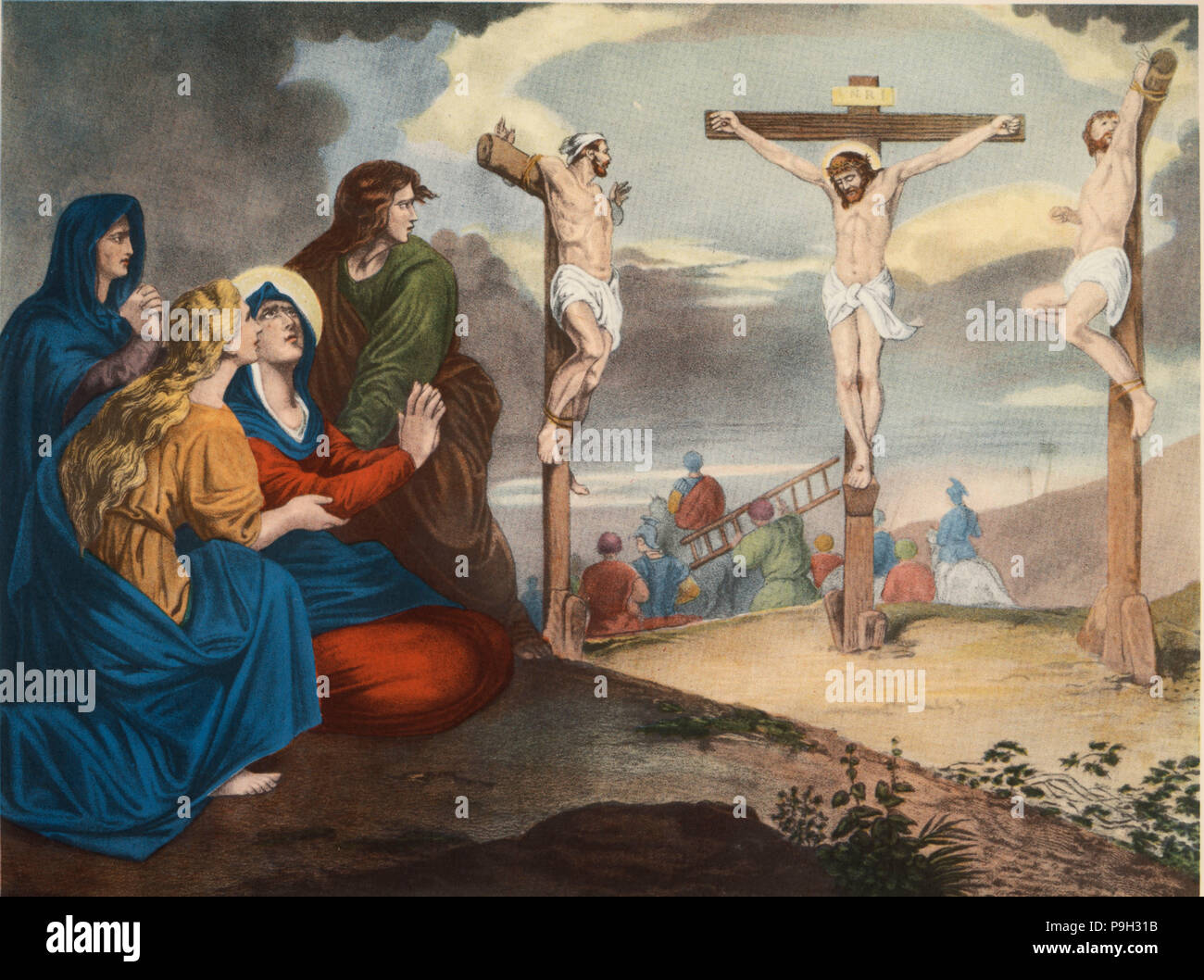

Where are you standing? This is the question most amateur artists forget to ask. If you're looking up from the ground, the feet will be huge and the head will be small. This "worm's eye view" makes the cross feel massive and intimidating.

The Low Angle

This is the "classic" devotional look. It puts the viewer in the position of the mourners—Mary or John—at the base of the hill. It creates a sense of awe.

✨ Don't miss: 100 Biggest Cities in the US: Why the Map You Know is Wrong

The Eye-Level View

Salvador Dalí famously broke all the rules with his Christ of Saint John of the Cross. He drew the view from above. It’s jarring. It feels like God the Father looking down. If you want your drawing to stand out, stop drawing it from the front. Try a side profile. Show the strain in the neck muscles.

Materials and the "Mood" of the Sketch

Charcoal is king here. I’ve tried doing this with fine-point pens, and it usually feels too clinical. Charcoal allows you to smudge. It lets you create those deep, cavernous shadows under the brow and around the hollows of the cheeks. The Crucifixion happened during an eclipse—the "darkness over the land"—so your drawing should embrace that. Don't be afraid to let the background disappear into total blackness.

If you're using graphite, vary your grades. Use a 4H for the faint outlines of the cross's grain, but keep an 8B handy for the hair and the shadows cast by the crown of thorns. The contrast is what makes the viewer stop scrolling or walking.

The Crown of Thorns: More Than Just a Circle

Stop drawing a literal circle of spikes. It looks like a cartoon. Real thorns, specifically those from the Ziziphus spina-christi plant (which many historians believe were used), are long, jagged, and messy. They don't sit on top of the head; they dig in. When you're drawing this, some thorns should be obscured by hair, and others should be angled sharply toward the scalp.

🔗 Read more: Cooper City FL Zip Codes: What Moving Here Is Actually Like

Blood is another tricky one. Less is usually more. If you overdo it, it becomes a horror movie poster. If you underdo it, it feels sanitized. The key is "pathway." Where does the liquid go? It follows the curve of the eyebrow. It drips onto the bridge of the nose. It follows the line of the arm toward the armpit.

Common Mistakes People Make

Most people make the cross too smooth. It was a rough-hewn execution tool, not a polished piece of church furniture. Use jagged, horizontal strokes to show the wood grain. Make it look heavy. Another mistake is the facial expression. There’s a fine line between "peaceful" and "bored." Even if you’re drawing Jesus at the moment of "It is finished," there should be a lingering ghost of the struggle he just went through.

- The Nails: They didn't go through the palms; the flesh would tear. They went through the wrists.

- The Feet: Often one is crossed over the other, but drawing them side-by-side can actually create a more stable, harrowing triangular base for your composition.

- The Inscription: The INRI sign wasn't always a neat little parchment. It was a wooden board. Make it look weathered.

Capturing the Emotion Without Being "Preachy"

The best art speaks for itself. You don't need to add glowing halos to tell the viewer who this is. The weight of the scene does the work. Some of the most powerful drawings of Jesus dying on the cross don't even show his face clearly. They focus on the hands—clenched or open in surrender.

Think about the lighting. If the light source is coming from one side, it creates a "Rembrandt lighting" effect where half the face is in shadow. This adds mystery. It makes the viewer lean in. It's about the "chiaroscuro"—the play between light and dark.

💡 You might also like: Why People That Died on Their Birthday Are More Common Than You Think

Actionable Steps for Your Next Piece

If you're ready to pick up the pencil, don't start with the face. Start with the "line of action."

- Sketch a curved vertical line that represents the spine and the hang of the body. This ensures your drawing doesn't look stiff.

- Block out the cross after you've placed the body. Many people do this backward and end up with a body that doesn't fit the wood.

- Focus on the "V" of the arms. Make sure the elbows have weight.

- Use a kneaded eraser to "pull" light out of the dark areas. This is great for highlighting the bridge of the nose or the tops of the knees.

- Study real muscles. Look at photos of rock climbers or gymnasts hanging from bars. See how the latissimus dorsi muscles (the ones under the armpits) flare out. That is the anatomical reality of your subject.

The most important thing is to keep going. Your first attempt might feel a bit flat, but that's okay. Art, much like the subject matter itself, is a process of trial, error, and eventual breakthrough. Keep your shadows deep and your lines intentional.

Next Steps for Success

To improve the realism of your work, spend thirty minutes sketching only the hands in different states of tension. Use a B or 2B pencil to practice the way skin folds around a fixed point, like a nail or a rope. Once you master the "stress points" of the body—the wrists, the ribcage, and the neck—the rest of the drawing will naturally fall into place with much more gravity and impact.