You’ve seen them everywhere. From those cheap carnival bags to the high-end aquariums in fancy hotel lobbies, goldfish are basically the "default" fish of the human imagination. But when you sit down to put pencil to paper, something weird happens. Most people think they know what a fish looks like. They don't. Your brain lies to you. It tells you a goldfish is just an orange oval with a triangle stuck on the back. Then you finish your drawing of a goldfish and it looks more like a floating sweet potato than a living creature.

It’s frustrating.

The reality is that Carassius auratus—the scientific name for our bubbly little friends—is a masterpiece of fluid dynamics and evolution. If you want to capture that on paper, you have to stop drawing "a fish" and start looking at the actual anatomy that makes these animals move. Did you know goldfish are actually a member of the carp family? That lineage matters. It dictates the bone structure, the scale pattern, and that specific way their mouths pout like they’re perpetually surprised by a secret.

The Anatomy Most People Ignore

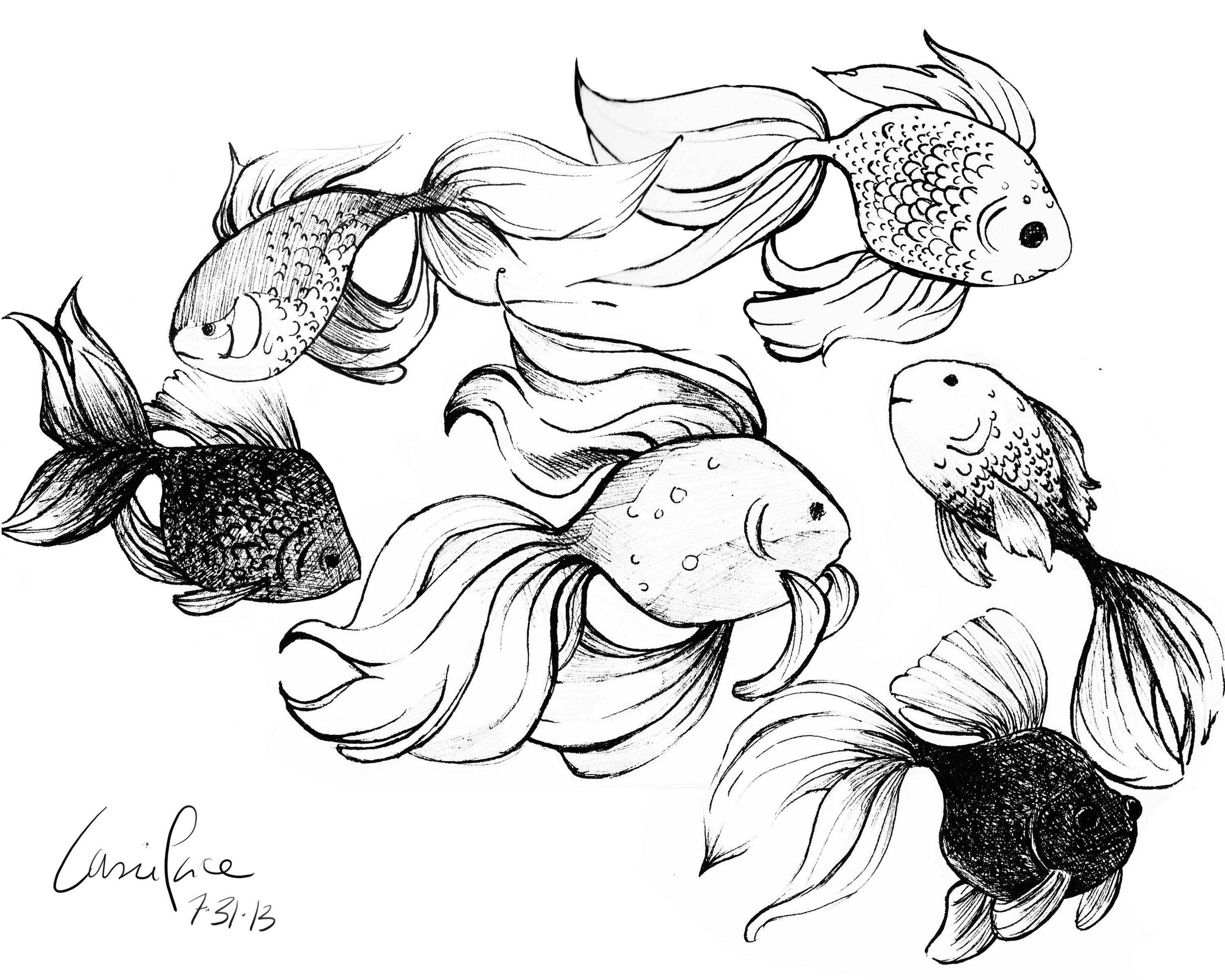

Look closely at a real Comet or Common goldfish. Their bodies aren't just flat shapes. They have volume. One of the biggest mistakes beginners make is ignoring the "depth" of the torso. A goldfish is thickest just behind the gills. If you draw it as a perfect circle or a skinny needle, it feels wrong. You need that gentle bulge in the midsection to suggest weight.

Then there’s the eye. Most people draw a circle with a black dot. In reality, a goldfish eye is slightly telescopic, especially in breeds like the Black Moor or the Celestial. Even in standard feeders, the eye has a distinct ring called the limbus. If you omit the slight "pop" of the eye socket from the head's silhouette, the fish looks flat. It looks dead.

Think about the scales. Don't draw every single one. Please. That’s a one-way ticket to a cluttered mess that looks like a chainmail suit. Instead, focus on the "lateral line." This is a visible line of sensory organs running down the side of the fish. If you just hint at the scales along this line and let the rest of the body stay smooth with some shading, the viewer’s brain will fill in the blanks. It’s a classic art trick. Less is more.

💡 You might also like: The Recipe Marble Pound Cake Secrets Professional Bakers Don't Usually Share

Nailing the "Flow" of the Fins

Fins are not stiff boards. They are basically silk ribbons attached to sticks. When you’re working on a drawing of a goldfish, the fins are where you show movement. If the fish is turning left, the tail (caudal fin) should be sweeping right. It’s physics.

The dorsal fin—the one on top—is a huge tell for the fish’s mood. A healthy, active goldfish usually has its dorsal fin pinned upright. A sick or stressed fish "clamps" its fin against its back. If you draw a drooping dorsal fin, your drawing will unintentionally look sad or sickly. You have to decide: is this a majestic Fantail or a zippy Common? A Fantail's fins are massive, often twice the length of the body, and they drape downward because of gravity and water resistance.

Why the Tail is the Hardest Part

Honestly, the tail is what breaks most artists. In breeds like the Oranda or the Ryukin, the tail isn't just one piece of skin. It’s often split into three or four lobes. It’s chaotic. It’s messy. To get it right, treat the tail like fabric. Draw the "ribs" (the rays) first as very light, sweeping lines. Then, connect them with thin, translucent webbing. Remember that the edges of the fins are often tattered or wavy, not perfectly straight lines.

Lighting and the "Metallic" Problem

Goldfish are shiny. That’s their whole brand. But "shiny" is hard to draw with a standard graphite pencil or even colored pencils. The secret isn't just adding white highlights. It’s about the contrast between the darkest shadows and the brightest spots.

If you look at a goldfish under a bright aquarium light, you’ll notice a "hot spot" on the upper curve of the back. This is where the light hits the scales directly. Around that hot spot, the orange gets deeper, almost turning into a burnt sienna or a deep red in the shadows near the belly. If you use one flat shade of orange, you’ve killed the realism.

📖 Related: Why the Man Black Hair Blue Eyes Combo is So Rare (and the Genetics Behind It)

You've got to layer. Start with a pale yellow base. Build up with a mid-tone orange. Save your deepest reds for the areas tucked under the gills and the base of the fins. And for the love of all things holy, leave some white paper showing for the highlights. Once you fill that in, you can't get it back without a messy eraser smudge.

Common Myths in Fish Illustration

People think goldfish only come in "gold." They don't. If you want your drawing of a goldfish to stand out, try a Shubunkin pattern. These are calico. They have splashes of blue, black, white, and red. Or try a Sarasa Coment, which is stark white with deep red patches.

Another myth? That they have a three-second memory. While not directly related to drawing, understanding that these are intelligent, social animals helps you capture "personality." An Oranda with a big, bumpy "wen" (the fleshy growth on its head) looks like a grumpy old man. A sleek Comet looks like an Olympic sprinter. Pick a personality before you pick up the pencil.

Technical Checklist for Your Next Sketch

Stop drawing the mouth as a simple "V." It’s a tube. Goldfish are bottom feeders; their mouths extend outward to suck up substrate. If you draw the mouth slightly open, you give the fish a sense of breathing. It makes the image feel "wet."

- The Silhouette Test: Black out your entire drawing. Does it still look like a goldfish? If it looks like a generic blob, you need to exaggerate the fins or the head shape.

- The Eye Placement: Ensure the eyes are symmetrical relative to the midline of the head. Since they are on the sides of the head, you usually won't see both fully from a side profile.

- The Gill Plate: The operculum (gill cover) should be a distinct curve. It defines where the head ends and the body begins. Without it, the fish is just a tube.

- The Weight of the Line: Use thick lines for the underbelly to suggest shadow and weight. Use very thin, wispy lines for the edges of the fins.

Beyond the Basics: Professional Insights

Professional illustrators like James Gurney or the legendary naturalist artists of the 19th century didn't just look at pictures. They studied the mechanics. If you’re struggling, look at 3D models of fish skeletons. It sounds like overkill, but knowing where the spine bends helps you avoid drawing "broken" fish. A goldfish can’t bend its body at a 90-degree angle in the middle; the curve has to be gradual.

👉 See also: Chuck E. Cheese in Boca Raton: Why This Location Still Wins Over Parents

Also, consider the environment. Water isn't invisible. It has particles. It refracts light. If you draw some tiny "bubbles" or a bit of floating debris (detritus), it grounds the fish in a real space. Suddenly, it’s not just a drawing on a white page; it’s an animal in an ecosystem.

Actionable Steps to Improve Right Now

Grab a reference photo that isn't a cartoon. Look for high-resolution macro photography.

First, gesture sketch the "flow" line. This is a single S-curve that represents the spine from the nose to the tip of the tail. This line dictates the energy of the piece. If this line is stiff, the drawing will be stiff.

Second, block in the three main masses: the head (a wedge), the torso (an egg), and the tail base (a small cylinder). Connect them with smooth transitions. Don't worry about the fins yet.

Third, add the fins as "attachments." Think of them like sails on a mast. They should follow the direction of the water flow. If the fish is moving forward, the fins should be pushed back slightly by the resistance of the water.

Finally, do not over-polish. The most beautiful drawings of goldfish often have a bit of "mess" to them. A few stray lines can suggest the shimmering, flickering nature of a fish in motion. If you make it too perfect, it looks like a plastic toy. Let it be a little wild. Use a soft 4B pencil for the darkest spots and a hard H pencil for the delicate fin rays. Contrast is your best friend. Now, get to work and stop making them look like potatoes.