You’ve probably seen it in a high school biology textbook. A long, beige-looking stick with knobby ends. That’s the femur. But honestly, a standard diagram of the femur usually does a pretty poor job of showing you just how much stress this single structure handles every time you jump or even just stand in line at the grocery store. It is the longest bone in the human body. It's also the strongest.

Think about it.

The femur has to support your entire upper body weight while pivoting inside the hip socket. It’s basically the biological equivalent of a skyscraper’s foundation pier, but it's alive, constantly remodeling itself, and surprisingly hollow in the middle. If you’re looking at a diagram right now, you aren't just looking at "leg bone." You’re looking at a masterpiece of evolutionary engineering that manages to be incredibly light while being stronger than concrete in some respects.

Breaking Down the Diagram of the Femur: The Upper End

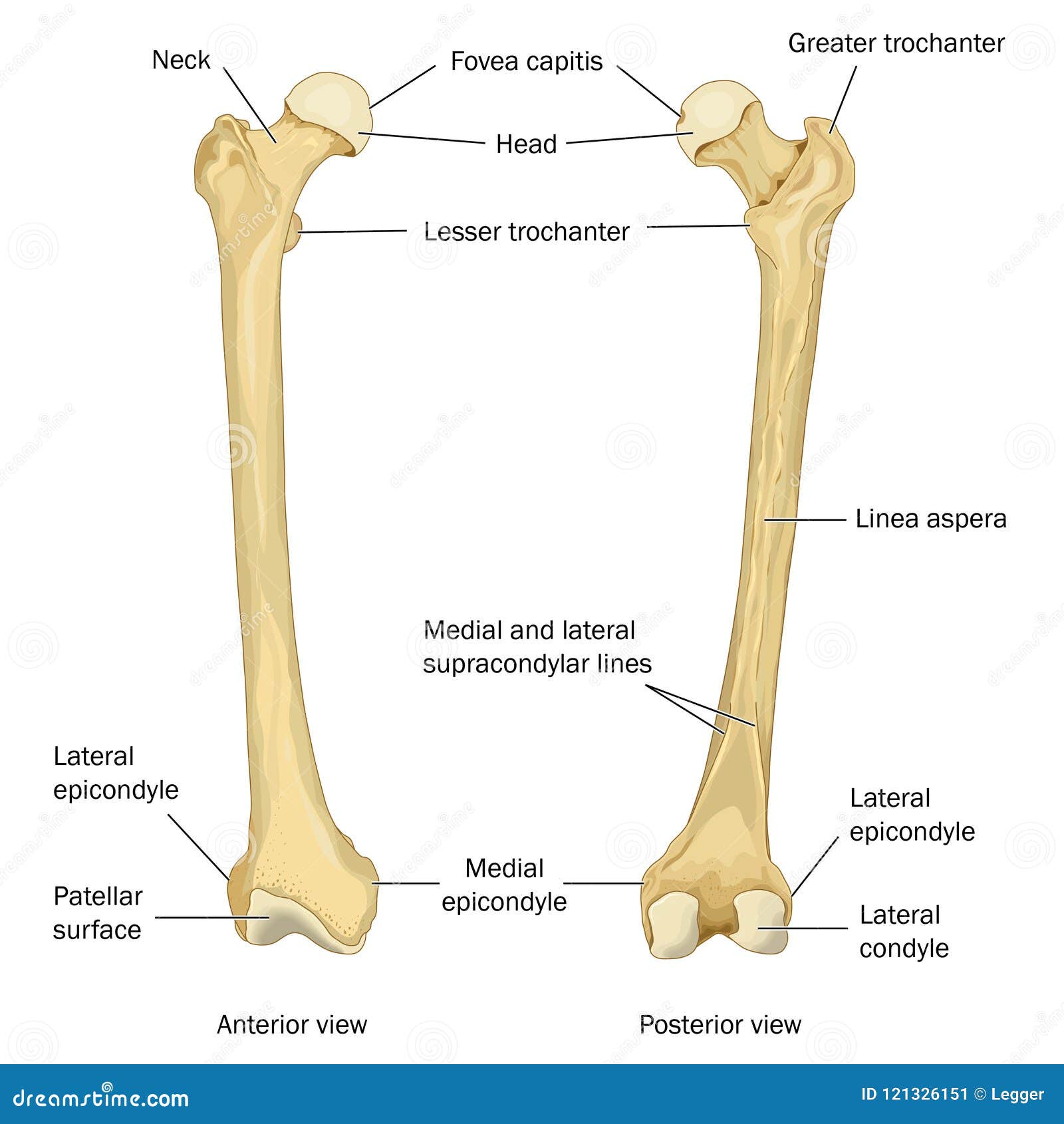

Most people start at the top. This is the proximal epiphysis. If you look at a detailed diagram of the femur, you’ll see the "head." It’s a smooth, ball-shaped structure. This fits into the acetabulum of your pelvis. It's a ball-and-socket joint, which is why you can move your leg in circles, unlike your knee which mostly just goes back and forth.

There’s a tiny little pit on that head called the fovea capitis. It looks like a mistake or a chip in the bone, but it’s actually an attachment point for a ligament.

Just below the head is the neck. This is a notorious spot. In older adults, especially those dealing with osteoporosis, this is where the bone usually snaps during a "broken hip." It’s a structural bottleneck. The angle of this neck—usually around 125 degrees in adults—is what allows us to walk upright without our knees knocking together constantly.

Then you have the big bumps. The Greater Trochanter sticks out on the side. You can actually feel this if you press hard on the side of your upper thigh. It’s not your hip joint; it’s a massive lever for your butt muscles. The Lesser Trochanter is smaller and sits on the inside. These aren't just random lumps. They are "traction epiphyses," meaning they grew that way because muscles were literally pulling on the bone while you were a kid, forcing the bone to thicken and reach out.

💡 You might also like: Is Tap Water Okay to Drink? The Messy Truth About Your Kitchen Faucet

The Shaft: Not Just a Straight Tube

The middle part is the diaphysis. In a basic diagram of the femur, it looks like a straight cylinder. It isn't. It actually bows slightly forward. This slight curve is brilliant because it gives the bone a bit of "spring" under heavy loads. If it were perfectly straight, it would be more brittle.

If you were to slice the shaft in half, you’d see the medullary cavity. This is where the yellow marrow lives. It’s mostly fat, but it’s a huge energy reserve. The walls of this "tube" are made of compact bone, which is dense and heavy.

On the back of the shaft, there’s a rough ridge called the linea aspera. This is the "rough line." It serves as an anchor point for the massive adductor muscles of your thigh. Without this ridge, your legs would just flop outward. It’s the structural spine of the bone shaft itself.

Why Bone Density Varies

Not all parts of the femur are built the same. At the ends, the bone is "spongy" or cancellous. It looks like a honeycomb. This isn't because the body is being cheap with materials. This lattice structure, called trabeculae, is aligned specifically along lines of stress. Wolff’s Law states that bone grows in response to the loads placed upon it.

If you lift heavy weights, your trabeculae get thicker. If you spend months in zero gravity, like an astronaut, your body decides it doesn't need that extra weight and starts reabsorbing the bone. This is why a diagram of the femur is really just a snapshot of a moment in time. Your actual femur is changing every single day.

The Bottom End: Where the Knee Happens

The distal end is where things get complicated. You’ll see two big rounded knobs called condyles. These sit on top of the tibia (your shin bone).

📖 Related: The Stanford Prison Experiment Unlocking the Truth: What Most People Get Wrong

- The Medial Condyle is on the inside.

- The Lateral Condyle is on the outside.

Between them is a deep groove called the intercondylar fossa. This is where your ACL (Anterior Cruciate Ligament) and PCL (Posterior Cruciate Ligament) live. When you see an athlete tear their ACL, it’s happening right in that little notch shown on the diagram of the femur.

On the front side, there’s a smooth surface called the patellar surface. This is the "track" that your kneecap slides in. If this track is too shallow, or if your muscles pull unevenly, your kneecap can pop out of place. It’s a very tight mechanical tolerance.

Real-World Stress and the "Steel" Comparison

Engineers love the femur. When you’re running, the force hitting this bone can be up to several times your body weight. For a 200-pound person, that’s over a thousand pounds of force pulsing through the femoral neck with every stride.

How doesn't it shatter?

It's the hydroxyapatite. That’s the mineral part. But it’s also the collagen. The collagen provides the flexibility. Without the minerals, your femur would be like rubber. Without the collagen, it would be like glass. It is a composite material that outshines most man-made substances in terms of weight-to-strength ratio.

Common Misconceptions Found in Basic Diagrams

Many people think the femur goes straight down from the hip to the knee.

Nope.

The femurs actually angle inward. This is called the Q-angle. Because our hips are wider than our knees, the bones have to slant. This slant is usually more pronounced in women because of a wider pelvis for childbirth. This is a major reason why female athletes are statistically more prone to certain knee injuries; the angle puts different sideways stress on the joint than a more vertical bone would.

👉 See also: In the Veins of the Drowning: The Dark Reality of Saltwater vs Freshwater

Another weird fact: the femur is responsible for a huge chunk of your height. Roughly 26% of a person's height comes from the femur. If you have "long legs," you specifically have a long femoral shaft.

Clinical Importance: When the Diagram Fails

Looking at a diagram of the femur is one thing; dealing with a femoral fracture is another. Because the bone is so strong, it takes a massive amount of energy to break the shaft—usually a high-speed car accident or a fall from a significant height.

Because the femur is surrounded by huge muscles (quads and hamstrings), a break can be life-threatening. These muscles are so strong that when the bone breaks, they contract and pull the jagged ends of the bone past each other. This can sever the femoral artery, which runs right alongside the bone. This is why paramedics use traction splints to literally pull the leg back into length. It’s not just about straightening the bone; it’s about preventing internal bleeding.

Actionable Takeaways for Bone Health

If you want to keep your femur as robust as the one in the diagram, you have to stress it. Bone is a "use it or lose it" tissue.

- Impact matters: Walking is good, but jumping or running creates the "impact" signals that tell osteoblasts (bone-building cells) to get to work.

- Nutrition isn't just Calcium: You need Vitamin D3 to actually absorb that calcium, and Vitamin K2 to make sure the calcium goes into your bones instead of your arteries.

- Resistance training: Lifting weights pulls on those trochanters we talked about earlier. That tension strengthens the entire bone structure, not just the muscles.

- Watch the posture: Slumping or sitting for 10 hours a day changes the way the femoral head sits in the socket, which can lead to premature wear of the labrum (the cartilage "O-ring" of the hip).

Understanding the diagram of the femur gives you a better appreciation for the literal pillars your body is built on. It isn't just a static object; it's a dynamic, pressurized, mineral-rich organ that is currently supporting your entire world. Next time you take a step, think about that femoral neck holding steady under the pressure. It's doing a lot of work for you.

To keep these structures healthy, focus on eccentric loading exercises like slow-tempo squats. This targets the bone-muscle interface at the hip and knee joints, reinforcing the areas most likely to wear down over time. Regular mobility work for the hip flexors also prevents the "pull" that can misalign the femoral head within the acetabulum, ensuring the wear and tear on your cartilage stays even and manageable as you age.